Sustainability experts: ‘Start preparing now’ for SEC climate rule, other disclosure regulations

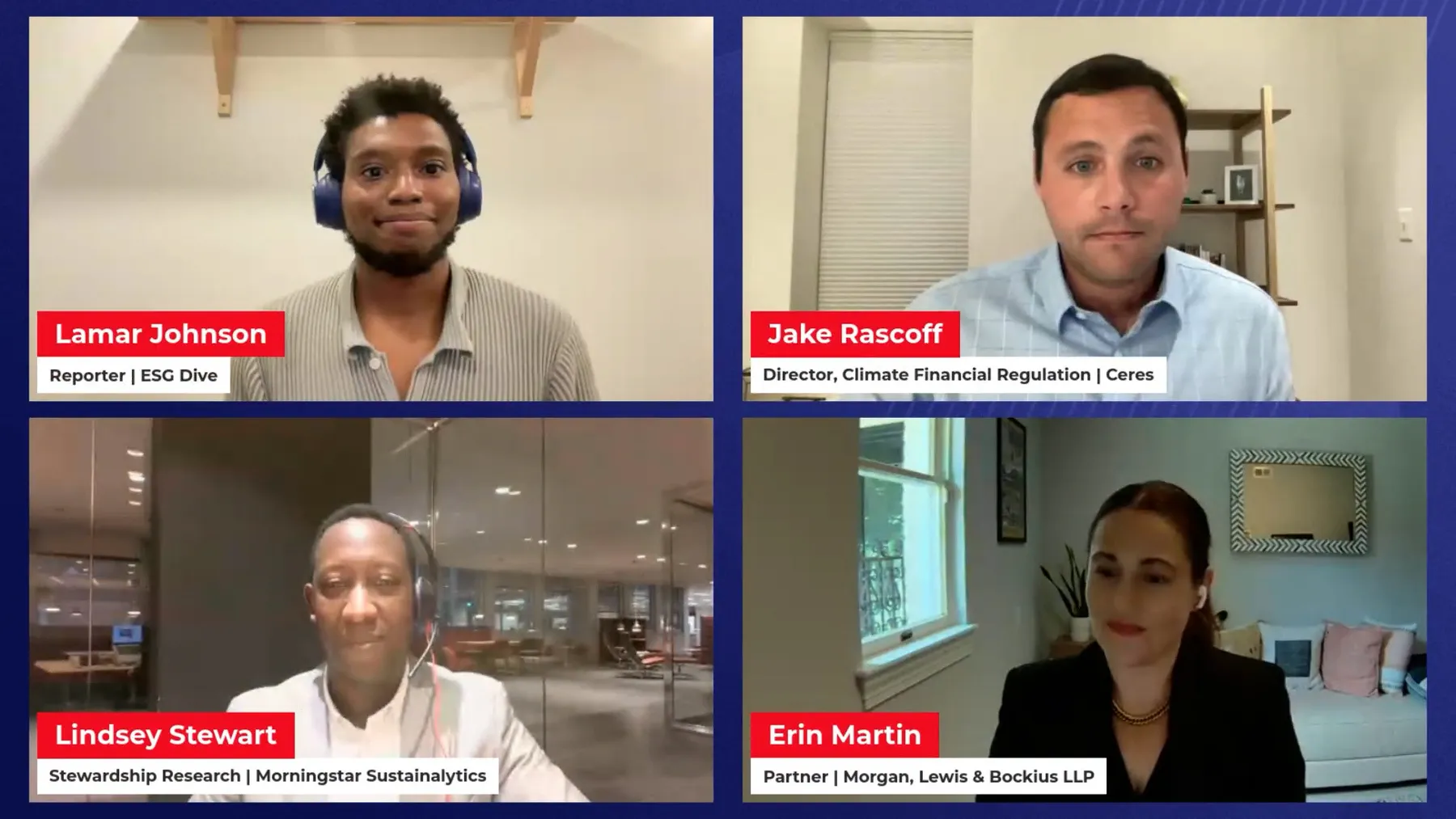

Editor’s note: This article recaps insights shared this month by sustainability and compliance experts from Morningstar, Ceres and Morgan, Lewis & Bockius on the current global climate regulatory environment during a virtual panel discussion. You can register here to watch a replay of the panel as well as the full event, “Risk & Reward: Complying with the SEC’s Climate Rule.”

The Securities and Exchange Commission’s climate risk disclosure rule has gone through quite the journey over the past two years. The rule was first proposed in 2022, mandating that companies describe their levels of greenhouse gas emissions and strategy toward reducing climate risk on their Form 10-K — an announcement that was met with pushback from both companies and politicians, particularly state and federal Republicans.

After pushing out its initial release and reviewing over 24,000 comments, the SEC passed the highly anticipated rule with a 3-2 vote earlier in March. The final rule scrapped scope 3 emissions disclosures entirely and scaled back scope 1 and scope 2 reporting requirements.

Despite the final rule being a pared-down version of the original, the regulation faced legal action almost immediately, both from critics who said the SEC had gone too far and from supporters who said the SEC hadn’t gone far enough. Consequently, the agency announced its decision to stay the rule in April as it works through these legal challenges.

Though the rule’s implementation has been halted as of now, it is just one of a plethora of climate regulations American corporations must potentially comply with going forward. This includes disclosure requirements both on home territory with California’s two climate bills — Senate Bills 253 and 261 — and abroad with frameworks like the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive.

On July 11, ESG Dive — in collaboration with its sister publication, CFO Dive — hosted a virtual event focusing on how industry leaders and C-suite executives could set their respective companies on a smart path to compliance against the backdrop of the SEC’s climate rule and other disclosure regulations. Experts from Ceres, Morningstar and Morgan, Lewis & Bockius shed light on what the recent coalescence of global reporting frameworks, the Supreme Court’s Chevron ruling and the plethora of legal challenges being faced by the SEC rule entail for climate disclosure requirements going forward.

Here are our top takeaways from the “Risk & Reward: Complying with the SEC’s Climate Rule” event.

Lagging enthusiasm for climate disclosures from regulators

After the SEC backed away from an initial rule that would have required all public companies to disclose their full scoped emissions, Lindsey Stewart, director of stewardship research and policy at Morningstar Sustainalytics, said the final rule showed a growing gap between disclosures investors want and the regulations being promulgated.

“We've really ended up with a very different rule from what was proposed in 2022,” Stewart said. “I think a lot of the high ambition that we saw around COP26 … where investors and companies were expected to lead the drive towards net-zero and towards climate, for reporting and disclosure of climate risk, a lot of that initial enthusiasm appears to have subsided in the time that has elapsed since.”

Stewart said the comment letters received by the SEC showed that, in addition to a baseline expectation of disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions and material climate risks and opportunities, investors are looking for company boards to have an “appropriate level of climate competence” across management.

How companies can best prepare for disclosure requirements

“You need to start preparing now,” said Erin Martin, a partner at Morgan Lewis who counsels public companies and their boards on securities regulation, capital markets transactions and corporate governance matters. Martin noted, however, that such preparations would also be affected by the “ton of uncertainty” surrounding disclosure requirements.

“That's going to be challenging for any public company … to address the changing and evolving landscape of regulation,” she said.

Martin said companies will have to consider things like where they should focus their time and resources and what counts as “financially material” to adhere to the growing disclosures.

She said that though determining what counts as financially material, and what isn’t, for a company might be time-intensive work, she has counseled her clients to “not sit and wait for the courts to decide,” alluding to the multiple legal challenges being faced by the SEC rule.

Martin noted that although the SEC’s legal battle might take upwards of 18 months to work through, eventually, some pieces of its disclosure rule — if not all of it — “will be required.”

“In order to ensure that you can provide accurate information responsive to the SEC requests and rules … you need to have processes in place today to anticipate those rules so you can ensure that you have accurate disclosure that you're providing, under the federal securities laws to your various stakeholders,” Martin said. “We can't just sit and wait.”

SEC rule vs. other climate disclosure regulations

Much has been said about how the SEC’s final rule compares to other disclosure requirements, such as California’s climate bills and Europe’s CSRD — which still require scope 3 emission disclosures. Jake Rascoff, director of climate financial regulation at sustainability nonprofit Ceres, said the importance of having a federal regulation that mandates climate disclosures on a financial report is irreplaceable.

“To those who say, why do we need the SEC rule when we have California and Europe and ISSB? I think there is no real replacement for having this information in an SEC filing,” Rascoff said during the panel.

He said investors defer to a company’s 10-K or S-1 filing — which provides information on a company’s activities and financial performance — when evaluating its due diligence or investment stewardship efforts. Rascoff said such SEC-mandated filings were “critically important for improving the consistency and comparability” of climate-risk disclosures.

Rascoff said an SEC filing is subject to “a level of rigor and scrutiny that doesn't necessarily exist for voluntary disclosures or even other … jurisdictions’ requirements.”

“The whole point of disclosure is to provide investors with the necessary information to make an informed investment decision, and then empower investors through that disclosure to make those determinations,” Martin noted when speaking about the SEC’s authority to mandate climate disclosures.

Challenges to compliance

Experts speaking on the July 11 panel said challenges to comply with the rule will vary depending on how an individual or group interacts with it. For investors, Stewart said, among the “challenges galore” will be navigating the various frameworks that already exist, including those in California and the EU. Companies navigating the fragmented environment will also have a more difficult time succinctly telling the story of how their sustainability mission coincides with their finance story.

“It certainly isn't going to be easy for companies to effectively communicate [their sustainability and finance story] across a fragmenting environment,” Stewart said. “So let's hope that this level of fragmentation doesn't last forever. I guess each jurisdiction had to start somewhere. We are where we are, and let's move forward from here.”

Martin, who spent more than 13 years in the SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance, said the rule will also place increased pressure on the agency’s regulators to determine compliance. She said the agency will need to ensure there is appropriate training and the right staff makeup to ensure they can determine if a company’s filing is materially compliant.

What the Chevron ruling means for ESG

The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, which overturned the Chevron doctrine, has threatened to upend administrative law procedures to a varying extent. The fate of regulations in a post-deference era may come down to a more case-by-case analysis. The doctrine was used to dismiss a challenge to a Department of Labor rule allowing pension fund managers to consider ESG factors, and that case is currently under consideration by an appeals court.

Rascoff said the challenges to the SEC’s rule in the U.S. Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals were made more challenging by the Loper Bright ruling. He said the agency is facing an “uphill battle” to protect its rule.

“Consensus opinion is [that] this rule is unlikely to survive litigation completely intact,” Rascoff said. “I would hope elements of it do survive.”

Martin said that while Chevron gave agencies leeway to interpret ambiguous statutes, the SEC has been given broad discretion to implement disclosures “it views to be necessary for investors” by the Securities Act of 1933. Because of this, she does not expect the Loper Bright decision to lead to any rules being immediately tossed. However, the ruling will give opponents an additional method by which to challenge the agency’s rulemaking process.

When it comes to the SEC’s current litigation, Martin said the lack of Chevron deference may add more support for arguments that the climate-risk disclosure rule is “arbitrary and capricious,” but does not mean the rule will be completely tossed.

“It's not, we have to start over. That's not what's at play here,” Martin said. “To be clear, [the Loper Bright ruling] does have a big impact. Just maybe not in this very small technical space right here.”