It's no big secret: The utility sector is undergoing a transformation, and new disruptive and distributed technologies are increasingly driving that change.

“We’re witnessing a convergence of old and new technologies,” Bob Stump, an Arizona utility regulator, said in a speech at Edison Electric Institute’s annual Powering the People event. “Distributed resources in some way or another are here to stay."

The majority of utility executives surveyed by Utility Dive acknowledge the utility business model needs to change and is indeed changing, with only 5% of those surveyed saying their utility should not build a business model for distributed energy resources.

Instead of swimming against the currents of change, utility sector leaders are searching for ways to incorporate more of these technologies onto the grid. But as they proliferate, stakeholders face several important questions over how to handle the growth of DERs and the future of role of the utility on the grid.

The debate over DER ownership

One debate that has grown alongside the expansion of DERs is who will own and operate these technologies.

Utility Dive’s 2016 survey of utility executives showed that 60% of those surveyed believe utilities should pair up with third party vendors to deploy DERs. However, nearly 59% said utilities should own and operate DERs, rate-basing their investments in these technologies — a more controversial approach that's not allowed in many state jurisdictions. These seemingly contradictory strategies suggests that utilities “are still weighing a variety of options for DER-centric business models and may even be pursuing multiple opportunities at the same time,” according to the survey.

As utilities deal with the move to less centralized power system, pilot projects have lent them experience in deploying and managing distributed resources, which has propelled some utilities to look into ownership of the resources. DER providers, on the other hand, worry that allowing regulated utilities into the market will cut into competition.

As utilities gear up for the proliferation of DERs in states like Arizona and California, the question of whether utilities can own DERs is being raised. Two Arizona utilities, Arizona Public Service and Tucson Electric Power, have already rolled out utility-owned rooftop solar programs and are searching for opportunities to incorporate more DERs. However, many states don’t allow utility ownership of DERs, which leaves open questions over what role utilities and DERs will play in the grid of the future.

Stump said that utility-ownership of DERs can "address market failures that third party providers aren’t addressing such as low-income ratepayers and bad credit scores.”

In New York, we're seeing an alternative approach emerge. The state's Reforming the Energy Vision (REV) initiative would limit utility ownership of DERs to situations where the competitive market has failed to deploy DERs to benefit the grid, more or less as Stump suggests. But REV aims to give utilities new primary role with regard to DERs: distribution system platform providers that facilitate the integration of DERs and the creation of distributed energy markets at the distribution level.

Whether or not other states will follow New York's innovative approach remains to be seen, but it's a model that's paving the way for utilities and DER providers to coexist and work together for the benefit of consumers and the grid.

“The utility must redefine its mission as it partners with consumers and third party providers,” Stump said at the event. “How will it adapt to a consumer-adapted model?”

Utilities as network providers

As DERs proliferate, utilities are starting to rethink their roles.

“So this [technology] is redefining all as a utility,” said Pedro Pizarro, the president of utility Southern California Edison. “We have to recognize that it’s a mind-shift change from [having all] the control but still recognize we should be at the center.”

One approach is a combination of developing a grid platform and partnering with third parties.

Ralph Izzo, the CEO of New Jersey utility PSEG, said at the conference that customers will likely value the utilities’ “network” experience.

Take Uber or Lyft for instance, he said. “So much of what we are seeing are people using networks and sharing assets to realize what other experience they are pursuit of [or ways to obtain what they want]. The value of our grid is only going to increase when we recognize the value of the partnerships that are here today.”

But first, “we have to invest in the grid,” Izzo told the crowd. “What’s central to all these things is a recognition that much of society is moving to recognize the value of networks.”

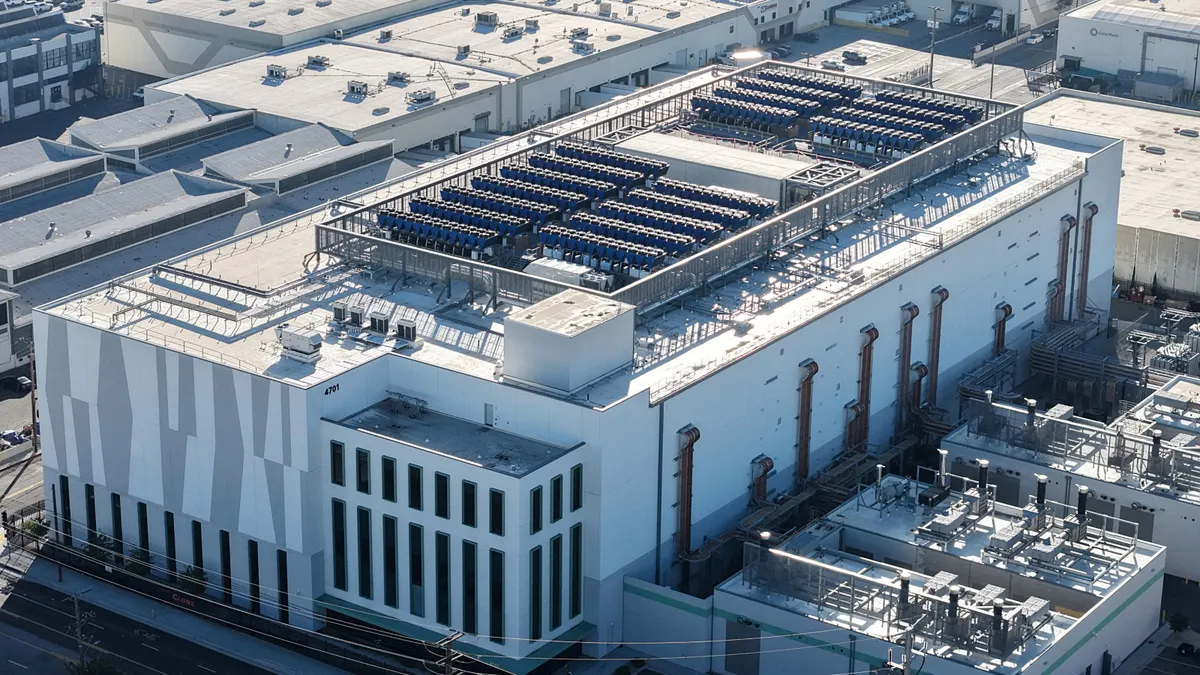

SCE’s Pizarro expressed the need for utilities to recognize their “natural function” as the operator of the “future smart grid.” His own utility, SCE, recently outlined a plan to invest up to $2.5 billion to modernize the grid in order to integrate more renewable energy and distributed resources.

California’s approach to grid modernization differs from REV: Instead of creating a distribution system platform provider, regulators directed the state’s IOUs to develop distribution resource plans that would enable two-way energy flows, allow utilities to better leverage DERs, and increase opportunities for the resources at the grid's edge.

“Consider how the roles might change in this distributed energy future,” Pizarro said. “[O]ne of the essential questions is, who should operate the [future] grid? We at SCE view that role as distribution system operator, as some have called it, [as] a natural part of a utility’s function because we have a real close interplay between our distribution control rooms and our crews in the field.”

Pizarro’s ultimate hope for this transformation is a “plug-and-play” grid, where the grid is a distribution platform that's been designed to allow for distributed resources to plug in.

“Maintain that plug and play grid and provide a market where third party providers provide grid services and they must be compensated fairly,” he said.

Down the road

What appears to stand in the way of this change happening is the existing utility regulatory model, stakeholders said at the conference.

SCE's Pizarro and Susan Kennedy, CEO of Advanced Microgrid Solutions and a former California Public Utilities Commissioner, both said the industry should push for a more flexible regulatory model that gives utilities more freedom in the market to procure technologies for the future grid.

“The mandate-subsidy approach is needed to spur change,” Kennedy said. “But the key issue is what the competitive market looks like and when you get there.”

One step forward would be scaled back regulatory involvement, instead of regulators trying to “control” the markets for DERs as they evolve, Kennedy said.

“The change will happen when the regulators will figure out what the markets are for these technologies,” Kennedy told the audience. “The biggest danger ... is the regulatory scheme that thinks they are in control. The regulatory scheme is really good at starting markets ... but not guiding markets through transition.”