Hydropower has long been a secondary member of the renewables family, pushed to the edges of sustainability discourses by past ecological damages and the booms in wind and solar energy.

But now, climate change and the need for clean and flexible baseload power is forcing hydro back into the spotlight, and forcing utilities and environmentalists alike to take a second look at the resource.

Technological advances are allowing utilities and environmental groups to reconsider the power of flowing waters that now provide over 7% of U.S. electricity and could be much more, according the latest market report from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

“Utilities backed away from hydropower because opposition from environmentalists made it too challenging,” explained DOE Wind and Water Power Program Manager Hoyt Battey. “It didn’t have the best public image for a long time because of some very legitimate concerns about its impact on waterway ecosystems. But we are getting a lot better at dealing with and mitigating those impacts.”

From its experience of almost four decades of work to protect U.S. waterways, American Rivers, a waterway conservation group, now believes “hydropower – done right – is an important part of our nation’s energy mix. But the key lies in getting it right.”

Badly developed hydropower has caused species extinctions and put others at risk.

“It must be sited, operated, and mitigated responsibly,” American Rivers says. And the group remains “very skeptical of the need for new dams or projects that dewater healthy streams.”

But climate change looms. Contemporary environmental laws and values and effective oversight by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) now make it possible to develop new hydropower capacity.

“America could double its hydropower capacity without building a single new dam,” American Rivers' website asserts.

“Hydropower development has a troubled history,” The Nature Conservancy concurred. But its emissions-free renewable base-load capacity and potential to provide storage capacity and flood control can’t be ignored.

“While some dams’ impacts clearly outweigh their benefits, in many places the most important question may not be whether to build a dam but rather about where and how hydropower is built,” Managing Director Giulio Boccaletti wrote. “If we fail to engage with the hydropower community, we will miss an enormous opportunity for positive impact.”

State of the hydropower market

There are 2,198 active U.S. hydropower facilities, representing 79.64 GW of capacity, by far the biggest of the renewables, according to DOE’s just-released "2014 Hydropower Market Report." Most of the capacity is in large projects built between 1930 and 1970.

Federal agencies, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Bureau of Reclamation, and the Tennessee Valley Authority, own nearly half of the capacity at very large dams. Publicly owned utilities, state agencies, and electric cooperatives own another 24% of capacity. The rest, mostly small sites, is privately owned.

Half of U.S. capacity is in Washington, California, and Oregon. At least 84% of the facilities do double service in recreation, flood control, irrigation, navigation, and/or water supply.

Production varies year to year and seasonally but 2013’s capacity factor was 39%, 2012’s was 40%, and 2011’s was 46%. The long term trend is toward a decreasing capacity factor due to the aging of facilities, the impact of environmental regulations, and reallocation of water.

On the other hand, hydropower’s average availability factor is 5% to 10% higher in the summer when electricity demand is higher. And 39 GW of U.S. capacity is rated as highly flexible.

Growth opportunities

There are growth opportunities for hydropower in four different classes, DOE's Battey said:

- Upgrades at existing hydropower facilities to increase efficiency and capacity

- Upgrading non-power dams (NPDs) to generate electricity

- New stream-reach development (NSD), which is building new hydropower facilities in untapped waterways

- Pumped storage hydropower facilities

There is a 12 GW technical potential for new capacity in NPD development, according to a 2012 DOE study.

The much more controversial NSD could provide another 65 GW of new capacity, according to a separate DOE assessment.

“Those 65 GW and 12 GW estimates are technical potentials, not practical resources,” Battey said. “You are never going to develop everything available.” The forthcoming DOE HydroVision study “is about figuring out what is reasonable and practical to develop,” he added. ”It is a complicated question.”

Utilities in hydro

Investor-owned utilities own a little less than a quarter of U.S. capacity and have been involved in hydropower since it became a significant power source. But there hasn’t been a lot of interest recently except in facility upgrades, Battey said. “There were easier, less contentious, less risky forms of generation to focus on.”

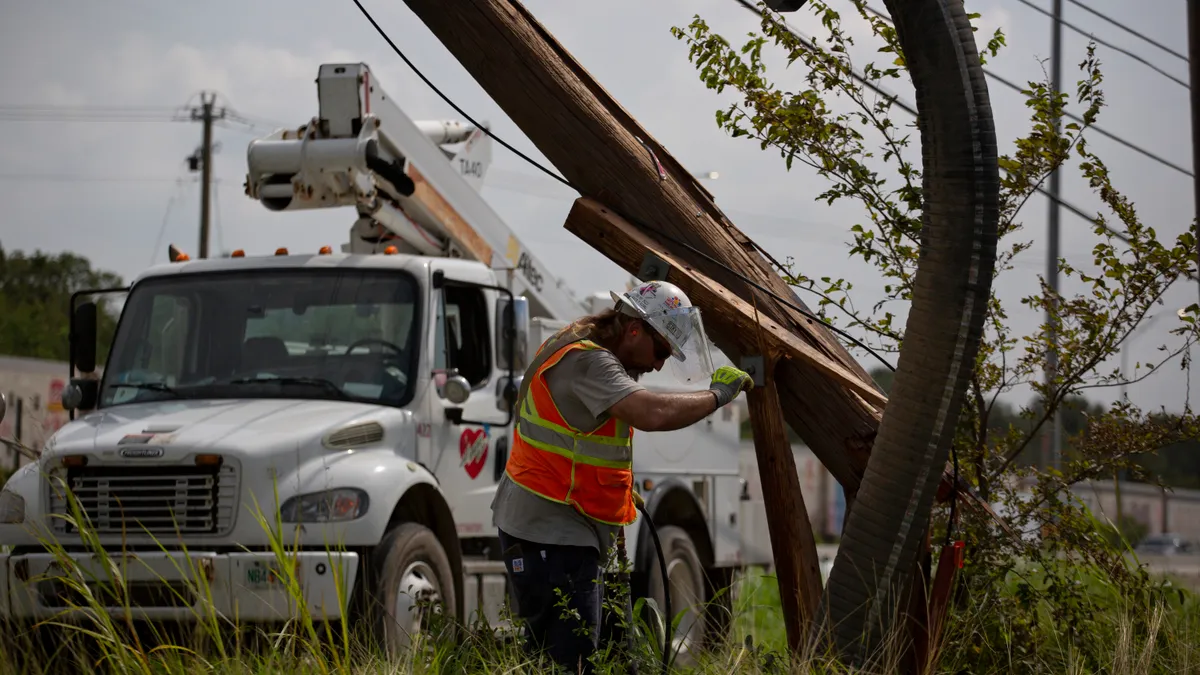

Regulatory uncertainty caused by litigation over environmental controversies is being resolved. In the Pacific Northwest, where pushback has been aggressive, “they had record salmon runs last year, showing how dramatic the improvement in minimizing impacts has been in the last 30 years,” Battey said. “We know so much more about low impact, more sustainable hydropower now. For continued development of existing infrastructure, a lot of the conservation groups are on-board.”

Pacific Gas and Electric, Southern Company, and Duke Energy are among the investor-owned utilities leading the sector, Battey said. Leaders on the municipal side are American Municipal Power in the Midwest and public utility districts in the Pacific Northwest.

Duke Energy has 33 hydropower facilities in its Carolinas territories, according to Spokesperson Lisa Parrish. The utility has no plans for new builds but regularly upgrades their efficiency “to get more generation and capacity from the same amount of water,” Parrish said. “The flexibility of this renewable energy resource is key to a reliable electric system and makes the inclusion of other renewable resources possible.”

Hydropower growth slowed to just 1.48 GW between 2005 and 2013, mostly in the form of facility upgrades and retrofits. At least $6 billion was invested in that period. There are 331 projects representing 4.37 GW of capacity in the FERC and Bureau of Reclamation Lease of Power Privilege pipeline, with 407 MW under construction and 315 MW approved for building.

To drive growth, DOE is working to overcome four significant barriers, Battey said.

- Research and development (R&D) on more efficient, lower cost, more modular technologies for NPD sites

- Extending awareness to public and private developers about those NPD opportunities where current technology could be cost-effective

- Classifying hydropower as “renewable” in more state renewables mandates

- Streamlining regulatory, permitting and licensing procedures

FERC heads the process but “a lot of other federal agencies are involved,” Battey said. “Data in the market report shows some projects can get approved quickly but some can take ten or more years.” Recent Congressional legislation was well-received by the industry and will be soon prove useful at removing some of the red tape, he added.

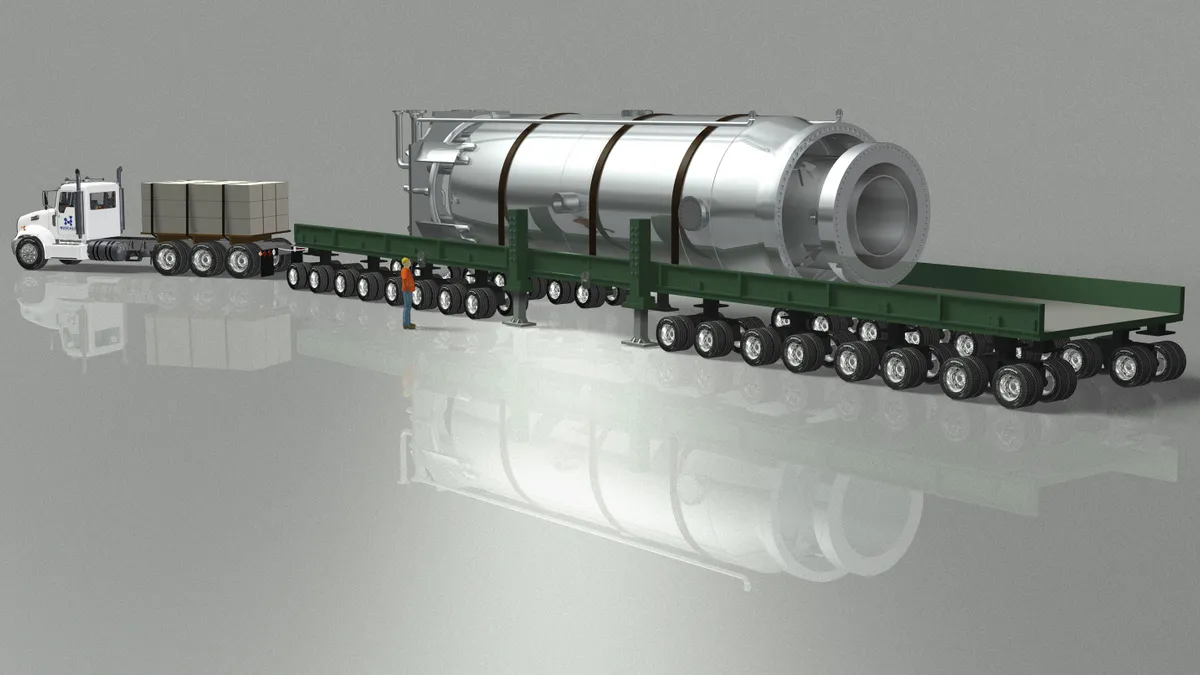

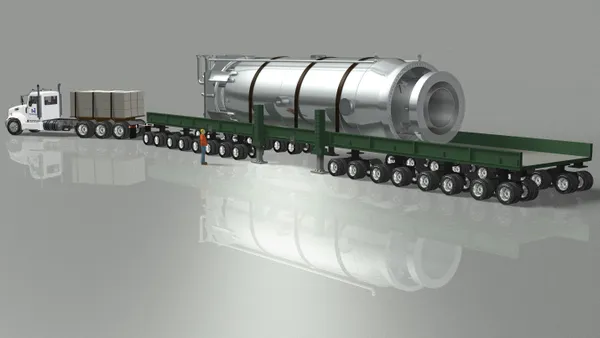

Pumped storage

Duke’s pumped storage hydroelectric technology is more important than ever because its quick start up time provides flexibility the utility needs, Parrish said. “Pumped storage functions like a giant water battery.”

Duke uses excess power from its inflexible plants to pump water from a lower reservoir to an upper reservoir. “At a moment’s notice,” Parrish explained, “the stored water can be used to meet peak demand for electricity.”

Pumped Storage Hydropower (PSH) is most of the global and U.S. utility-scale energy storage and is regularly used around the world for ancillary grid services to bolster reliability, according to DOE’s market report.

The U.S. has 42 PSH facilities representing a 21.6 GW capacity, but only one 40 MW site has been built since 1995. None are presently in construction though existing facilities are being upgraded. Most operating facilities were built between 1960 and 1990 to store the excess generation of nuclear and fossil plants that do not dial down and are expensive to turn off during periods of diminished demand.

“I smirk when I hear there is no way to effectively store energy because we have had it for a long time,” Battey said. “As the need for additional storage and grid flexibility develops, there are huge opportunities in pumped storage.” At large scale, storing off-peak power and selling it at peak demand periods is cost competitive and extremely reliable, he added.

Between 2000 and 2014, according to the North American Electric Reliability Council, PSH’s availability factor has been above 90% every summer but as low as 75% in some fall and spring seasons.

There are 51 PSH proposals under FERC consideration, representing 39 GW of potential storage capacity. But only three have submitted license applications. The others are working on permitting. The FERC did issue go-aheads on the 1,300 MW Eagle Mountain and the 400 MW Iowa Hill projects in California last year, driven by the urgency of an increasing renewables penetration as the state rushes toward a 33% renewables by 2020 mandate.

Current PSH technology is only cost competitive at very large capacities, Battey said. But today’s electricity markets more typically require stored capacity of 50 MW to 100 MW for 8 hours. For capacity markets and for ancillary services like spinning and non-spinning reserves and other regulation services the larger facilities “wouldn’t be economic.”

DOE is funding research on ways to develop PSH at a scale that would serve the fast response needs of a grid with increasing levels of variable renewables, Battey said. “There are already advanced technologies being deployed in Europe and Asia that have almost as much flexibility as natural gas plants.”

Hydro's wild card: Climate change

Hydropower, along with other renewables, is key in the fight against climate change and the greenhouse gas emissions that cause it, but it is also subject to the climatic impacts as well.

As Utility Dive has reported, the severe drought that has strapped California and other Western states for four years is severely hampering hydropower outlet. Snowpack after this past winter, a crucial measure of future reservoir levels and hydro output, was only 3% of the average this year in parts of California, and the state's largest reservoirs are filled to just 66% of average conditions.

The situation has gotten so bad that Energy Secretary Moniz said there is "certainly a risk" that California could face brownouts this summer. "Hydropower is a renewable," he said, "but if you look historically, there is actually quite a bit of fluctuation from year to year, depending upon what happens over the winter."

Several hydropower producers have asked federal regulators to loosen restrictions on reservoir water releases. In April, PG&E requested a one year variance of license requirements for its 206 MW Mokelumne river project. The utility wants to cut water flows in one area 60%, and said snowpack on April 1, 2015 was the lowest since records began in 1918 — only 13% of average conditions.

Still, Argus noted that California hydro output was above where it was a year before in April, and DOE still expects hydro to grow, despite drought conditions in the West. The report points out that a number of hydro facilities have already implemented climate change adaptation strategies, and that new technologies can help dams generate more power with less water.

"For instance," the report reads, "Reclamation has installed new wide head range turbines at Hoover Dam that allow more efficient operation over a wider range of reservoir levels than the turbines used until now."

The effects of climate change on precipitation are expected to be highly localized as well, scientists say. While a warming climate can exacerbate droughts and other severe weather events, it is also expected to raise precipitation levels in the aggregate, which could assist in more hydro generation in some areas.

For all its struggles past and present, Battey still expects hydropower to have a significant and growing role in the U.S. generation mix throughout the 21st century.

Hydropower “is not always the first renewable energy resource people think of,” he said. “But it is still a growing and developing resource that offers a lot of opportunity.”