Dive Brief:

-

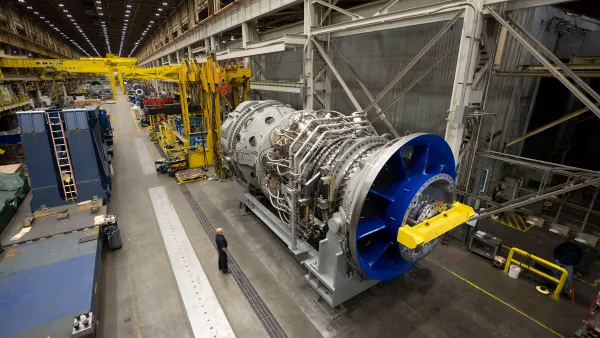

Hydrogen could play multiple roles in the clean energy transition, from decarbonizing heavy industry to expanding energy storage — and even fixing the electric grid, according to panelists assembled by the nonprofit Our Energy Policy. But speakers at Wednesday's event diverged in their vision of how hydrogen will be implemented.

-

To Jennifer Arasimowicz, executive vice president of FuelCell Energy, vehicles represent the "biggest up and coming use" for hydrogen, especially for applications such as long-haul trucking, where downtime for recharging creates costly inefficiencies. But Janice Lin, founder and CEO of the Green Hydrogen Coalition, sees potential in decarbonizing existing applications of hydrogen, such as fertilizer.

-

Speakers also diverged on potential hydrogen transition strategies, including questions about the utility of hydrogen from carbon-based sources, and how to distribute hydrogen.

Dive Insight:

What role might hydrogen play in a clean energy economy? It depends on who you ask.

Hydrogen represents a clear opportunity for producers of renewable energy, according to Lin. California producers, for example, curtailed enough wind and solar energy last year to fuel 200,000 vehicles for a full year, had that energy been converted to hydrogen.

"Green hydrogen is a game changer in our fight against climate change, because it enables decarbonization of difficult to decarbonize sectors," Lin said. "Green hydrogen can convert low cost wind and solar to a flexible zero carbon fuel that can displace many fossil fuel applications."

Demand for this hydrogen already exists, Lin said, with some 100 million metric tons of hydrogen already in use in industrial applications. Most of today's hydrogen, she said, is produced by using steam methane reforming or other methods to extract hydrogen from fossil fuels. Green energy could decarbonize this existing industry by using curtailed wind and solar energy to split water into hydrogen and oxygen by way of electrolysis.

But there is another potential way to view hydrogen, Arasimowicz said: as energy storage.

"We could take excess wind and solar and rather than curtail it, convert it to hydrogen and store it," she said. "And then at night reverse it and use hydrogen to generate electricity."

Batteries, Arasimowicz added, may be a cheaper means of storing energy in the short-term, but hydrogen can be stored indefinitely, offering a potential solution to current challenges weighing on the energy industry.

"Batteries aren't going to sustain long-duration grid outages," Arasimowicz said. "Texas for example, you're not going to get enough battery storage to supply the grid for those types of outages."

Hydrogen could also offer consumers an important alternative to EVs, which Morry Markowitz, president of the Fuel Cell and Hydrogen Energy Association, argued won't meet the transportation needs of all consumers. In addition to heavy industry, he said, some consumers don't have the means to charge an electric vehicle. Other households, he said, have just one vehicle and require greater range than is possible with an EV.

"The consumer is going to be the one, whether the retail or commercial user, that will determine where the application best fits their needs," Markowitz said.

Hydrogen distribution, Lin said, also remains an area with unanswered questions. Green hydrogen fuel could be produced locally, with electrolyzers powered by the grid. Or hydrogen could come from centralized plants with the gas itself piped from regions of low-cost renewable energy production to areas of high demand. The latter scenario, Markowitz said, could provide utilities with a work-around to current barriers slowing the expansion of the electrical grid.

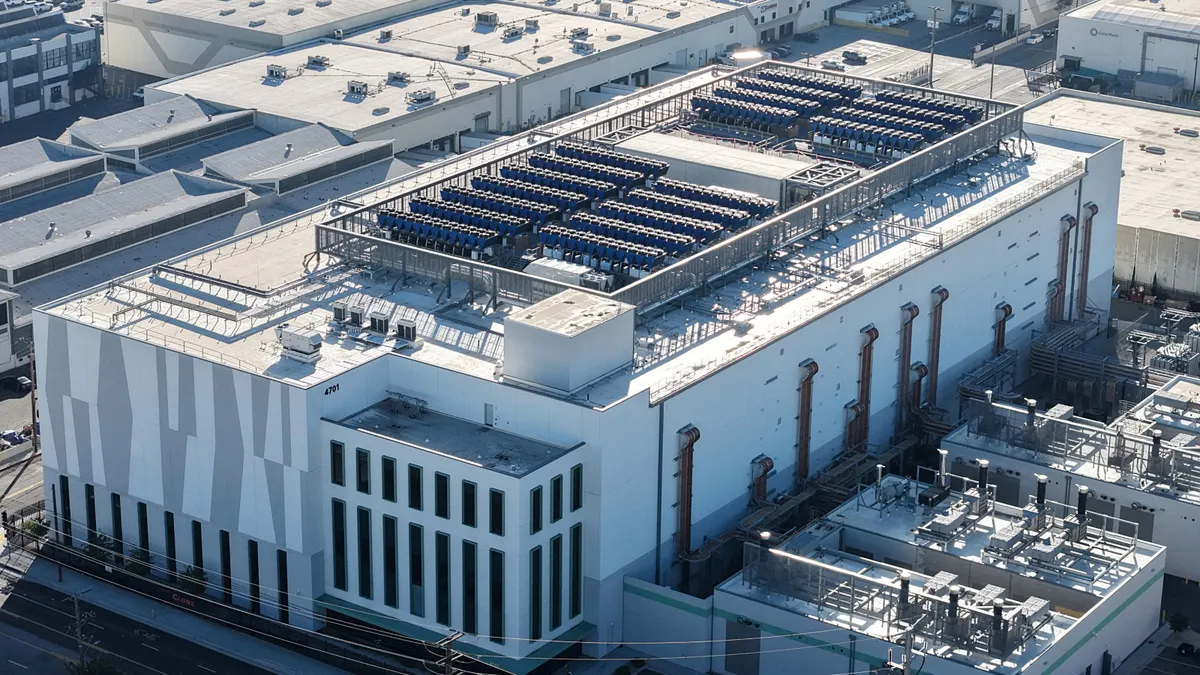

"So I believe fuel cells will play a role in distributed generation, in data centers or in cities where you need to grow capacity, but you can't get the distribution there," he said.

The role of blue hydrogen — hydrogen produced with carbon capture or other emissions-reducing technologies — also remains an area of debate. While Lin argued there are many affordable pathways to green hydrogen production, Arasimowicz said green hydrogen remains too expensive and that blue hydrogen could provide a bridge in the near-term, while also reducing emissions from existing industries. Natural gas production, she said, currently produces excess methane, which is burned off as a means of disposal. But that gas could be captured and converted into hydrogen, Arasimowicz said, reducing more emissions in the near-term.

"We think what should be looked at is the impact — what can be displaced," Arasimowicz said.