Virtual power plants can realize their full potential with improved control technologies, streamlined communications and customer-engaging compensation, utilities, providers and analysts agree.

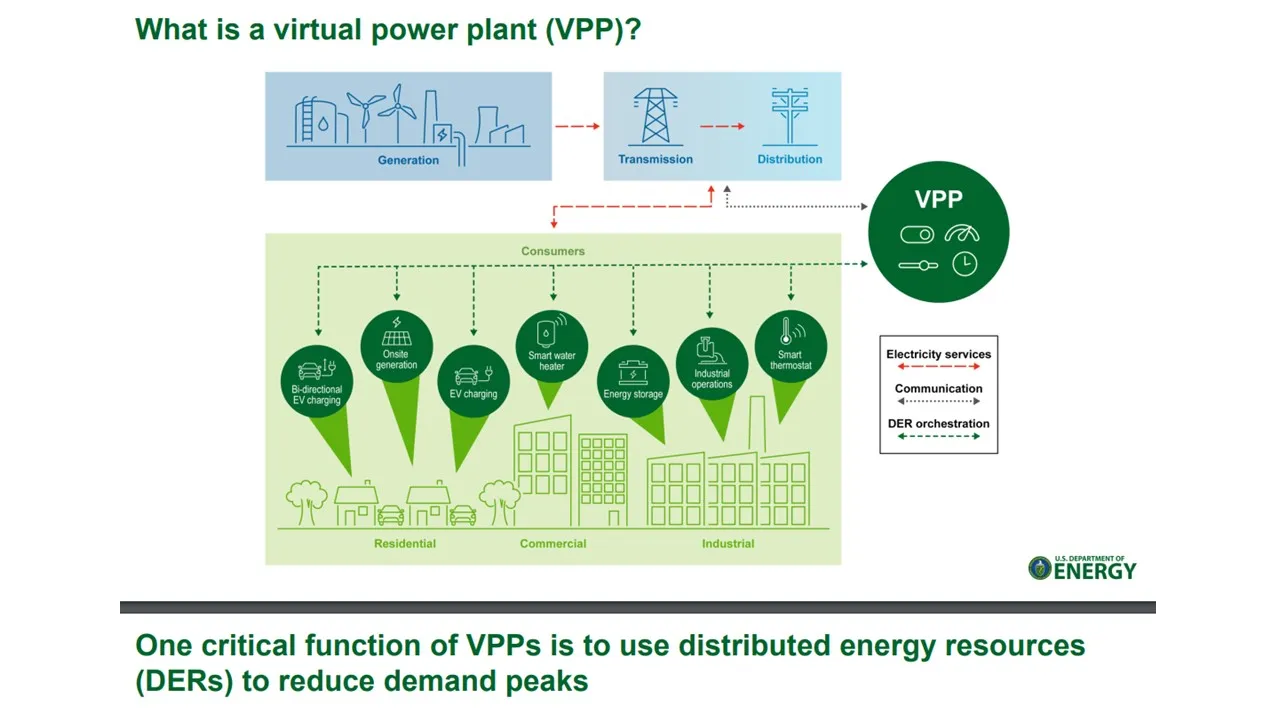

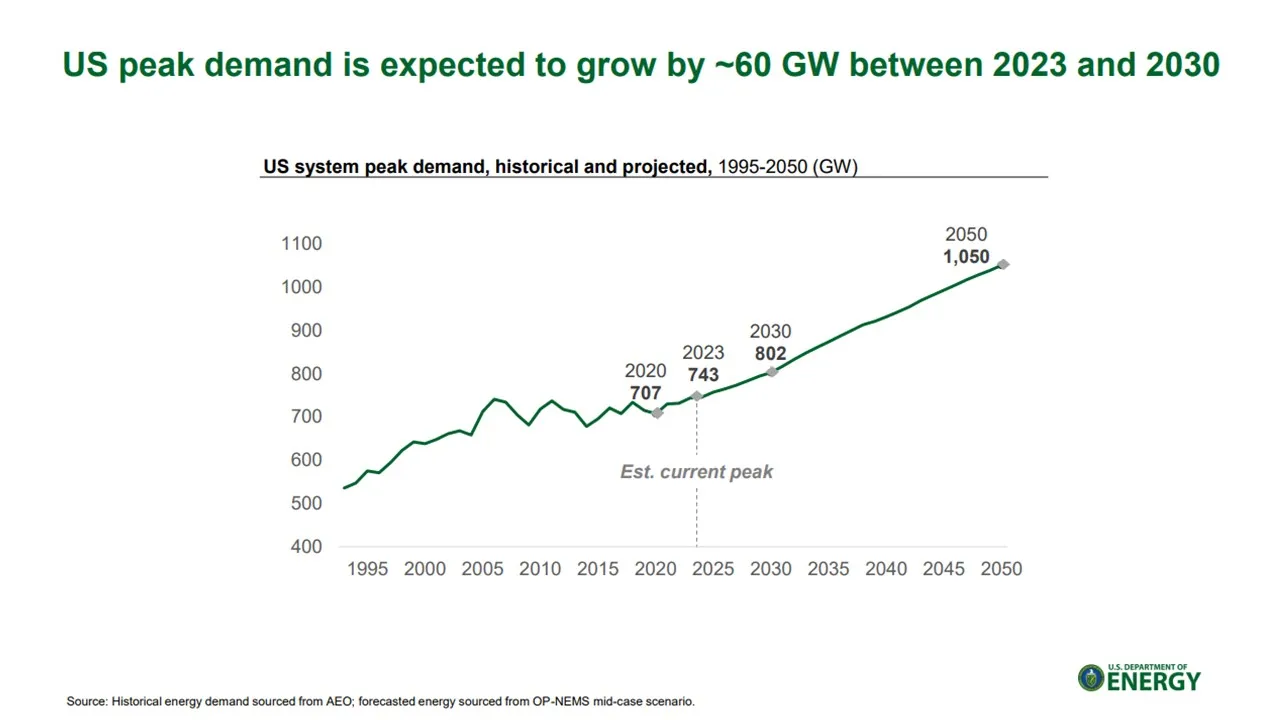

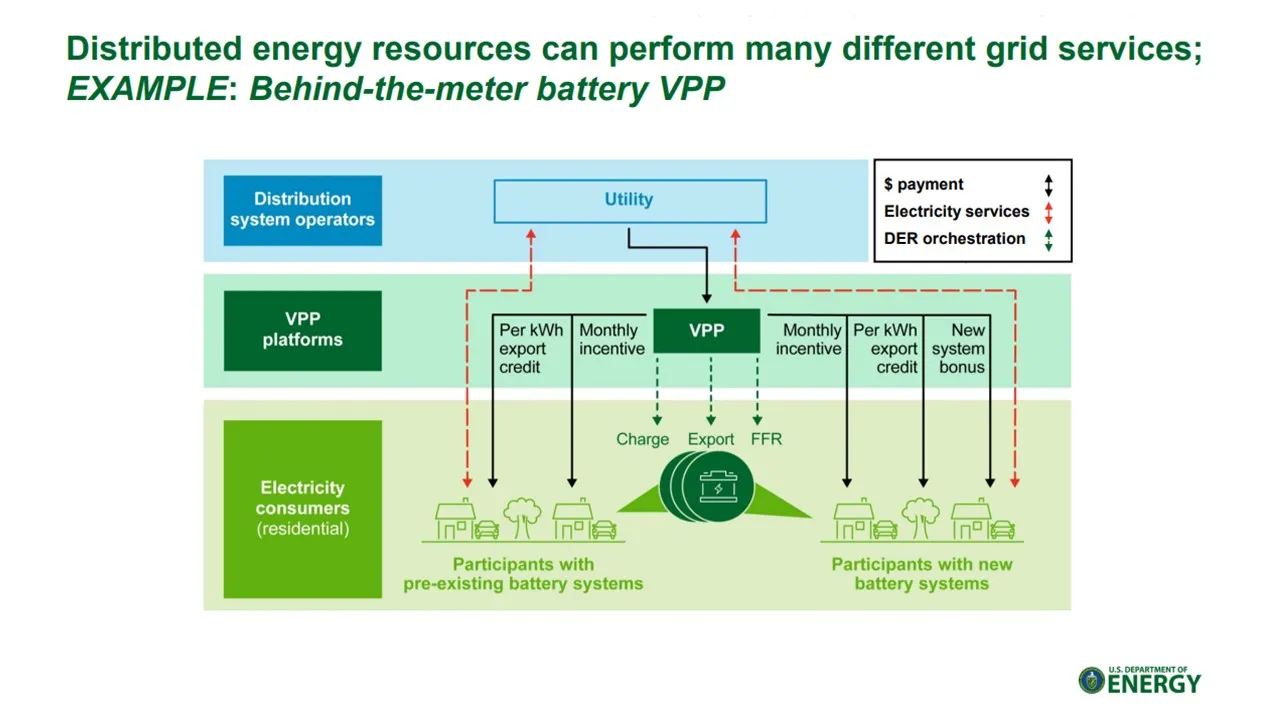

VPPs are aggregations of distributed energy resources managed by sophisticated software to meet power system needs, including load reductions and system stability. By mid-2023, North America had more than 500 of them with up to 60 GW of total capacity, according to one estimate. By 2030, VPP flexible capacity could scale up to 160 GW and serve almost 20% of the projected 802 GW U.S. peak load, the Department of Energy says.

“Scaling up DER integration” into VPPs will face challenges, wrote DOE Loan Programs Office Director Jigar Shah in September 2022. But the obstacles are “far from intractable, and well-worth the cascade of benefits,” he added.

Even analysts whose research shows VPPs can be a key power system solution agree the challenges to scaling are real and are only beginning to be addressed.

To grow, VPPs can and must be “fully compensated for the value they can provide” and “customers need to trust that participating won’t inconvenience them,” said Brattle Group Principal Ryan Hledik, whose research has identified signifjcant VPP values. And vital VPP system stability services may require technology investments to “connect directly into utility control systems,” he added.

Scaling VPPs will likely impose new costs for operations technologies, VPP providers, utilities and analysts said. It will also require new planning processes that recognize the multiple new values of VPPs’ flexible DER elements, and confronting regulators with the need for system standardizations, many also agree.

Operational challenges

VPPs vary significantly by jurisdiction and provider, and there are no recognized communications standards to streamline their response to indicators that show a need for load reductions or system stability services.

Pacific Gas and Electric has “approximately 412 MW” of VPPs and is “actively looking to integrate more,” said company spokesperson Paul Doherty. Its VPPs are part of state, aggregator-led and utility-led programs with partners including Tesla, Sunrun and BMW, he added.

PG&E is implementing a new system-wide Advanced Distribution Management System coupled with a Distributed Energy Resource Management System, Doherty said. It is also investing in communications systems which “will enable incremental VPP use cases,” he added.

Rocky Mountain Power has standardized its Utah Wattsmart solar and battery VPP operations by establishing criteria battery manufacturers must meet to participate, said the utility’s Vice President of Customer Experience and Innovation William Comeau. It therefore “has no need for DERMS,” he added.

To qualify for Rocky Mountain Power’s load reduction and stability services programs, batteries must meet capacity, cycle life and daily charge-discharge capability criteria, Comeau said. With the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers’ 2030.5 protocol for DER interconnection and 30 second interval data available to the utility, Rocky Mountain Power has full dispatch control of the VPP’s full value, he added.

“The IEEE 2030.5 DER interconnection standard could be a solution” for national interoperability between all DER and all system operators, agreed Scott Harden, chief technology officer for global innovation with power system technologies provider Schneider Electric. The American National Standards Institute or another national standards agency “could take the lead” to develop another standard to serve the same purpose, he said.

“The control room and communications technologies to scale VPPs have been available for a decade and are proven,” Harden continued. But scaling VPPs will require “development of a standardized open communications protocol and open DER registry to allow all DER to compete in retail market-like scenarios,” he said.

Duke Energy’s just approved 60 MW PowerPair pilot offers a $9,000 upfront incentive to customers who buy batteries and allow limited utility control of them, added Duke Energy Senior Vice President, Pricing and Customer Solutions, Lon Huber. But automated interoperable communications and dispatch “will be critical” to reaching “meaningful scale,” he agreed.

To scale VPPs, Hawaiian Electric will require “smarter, faster” control room and communications technologies for visibility, control and dynamic optimization, agreed company spokesperson Darren Pai.

VPPs are a growing part of National Grid's resource mix, National Grid Director, Future of Electric for Customers, Joshua Tom added. Additional control room and data management technologies are all "really important" to further scale them, he said.

But Chris Rauscher, head of grid services and VPPs for Sunrun, said, “both PG&E’s sophisticated control room operations and Puerto Rico’s LUMA’s fairly rudimentary operations allow partnering in Sunrun VPPs” and “there are no technical, metering or software challenges.”

According to Rauscher, the claim that more sophisticated control room technologies are necessary is “an excuse” for delaying expansion of VPP programs. Sunrun, however, “dispatches its own fleet of DER” without integrating into utility operations, he acknowledged.

Brattle’s Hledik added that for “real-time grid balancing services at scale, VPPs may need to connect directly” with utility operations.

To provide system stability services, the Sunverge-Delmarva Power-PJM Interconnection 500 kW Elk Neck, Maryland, VPP had to meet PJM’s “real-time operational requirements,” said Sunverge Energy CEO Martin Milani. It had to provide two-second telemetry, two-second meter scans, and under ten-second aggregator responses, he added.

“Scaling VPPs and providing the full range of system services will require state regulator-approved investments in much faster telemetry and metering and communication systems,” Milani said.

Nevertheless, “any utility considering resource procurements should compare VPP peak generation costs with near term costs for alternatives,” Sunrun’s Rauscher said.

But attracting consumer participation in virtual power plants at the scale projected by DOE and Brattle raises other questions, utilities, VPP providers and analysts widely agree.

Compensation to attract participation

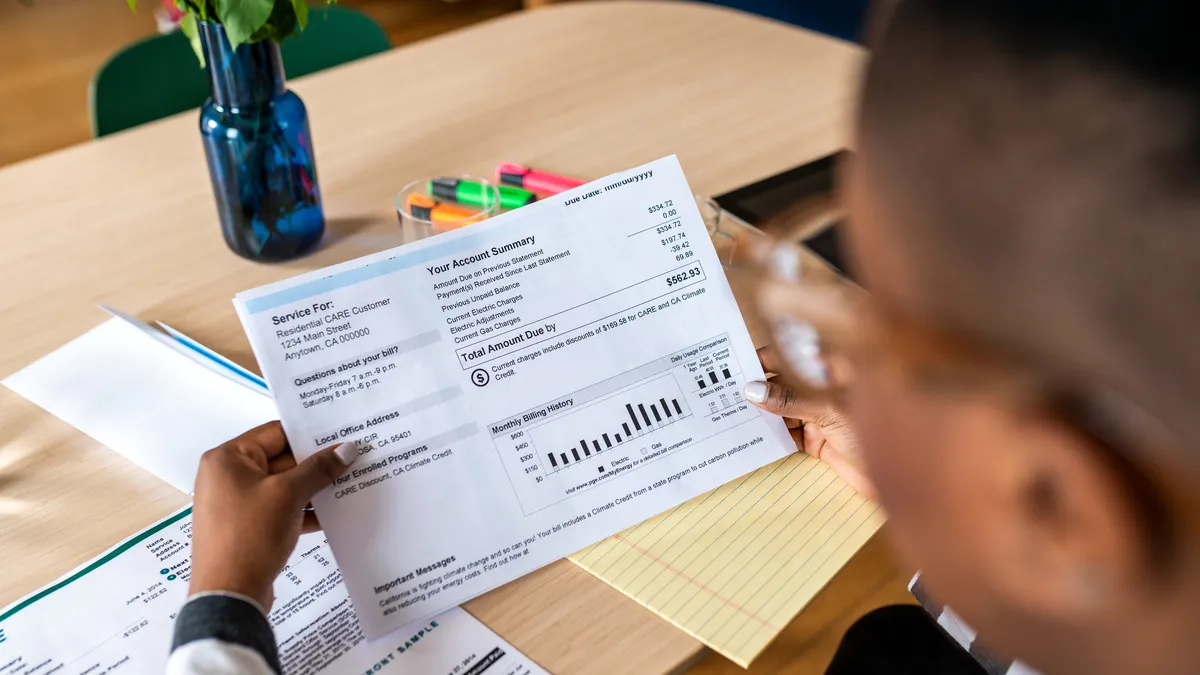

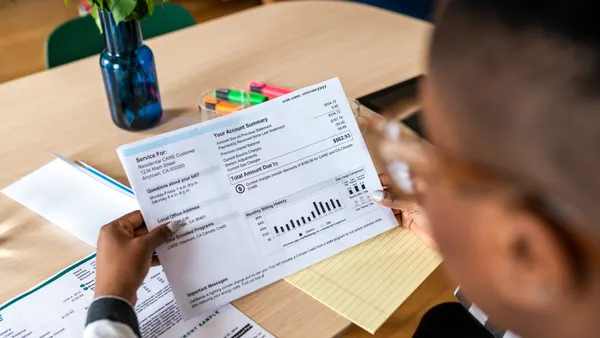

The VPP DER elements are typically owned by customers and therefore are bargains for utilities and system operators compared to traditional infrastructure investments, but customer-owners must see the value proposition in participating, many stakeholders said.

“The biggest issue now is developing market drivers,” said Ed Smeloff, independent consultant to the Center for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Technologies.

California’s Demand Side Grid Support program is “a driver toward full market participation” for customer-owned DER because it compensates VPP aggregators for using them to reduce loads at periods of very high demand, Smeloff said. “More market integrated compensation programs will evolve as interconnection codes and communications standards are developed for bigger-scale VPPs offering more system services,” he added.

“Customers also need to learn to trust that limited third party control of their DER will not compromise the value of their investments and will lower bills,” Smeloff said. “That will require utilities and aggregators to recognize customers have different values and intentions about DER,” he added.

The Delmarva Power-PJM-Sunverge pilot faces that exact challenge, said Pearl Donohoo-Vallett, director of regulatory strategy and services for Delmarva parent Pepco Holdings. Delmarva “gave batteries to customers at no charge in return for allowing utility control when demand drives prices high, but customers wanted the batteries for their own backup power,” she added.

Delmarva is now working to recognize both “customer needs and evolving system needs,” Donohoo-Vallett said. The more system services the DER meet, “the more value they have, and the higher the compensation to the customer,” she added.

“A scalable program’s economics must attract participation, but it has to be cost-effective” for all utility customers, Duke’s Huber noted.

But some pricing to VPP aggregators and DER customer-owners “does not provide a compelling price signal to participate,” responded Benjamin Hertz-Shargel, global head of grid edge for Wood Mackenzie.

New York and New England grid operators compensate VPPs for wholesale market capacity, Hertz-Shargel said. But compensation for distribution system value, like National Grid’s ConnectedSolutions program and Consolidated Edison’s Distribution Load Relief program, would “make the value proposition to customers more compelling,” he added.

ConnectedSolutions and California’s Demand Side Grid Support program were also endorsed by Mathew Sachs, senior vice president, strategic planning and business development for leading virtual power plant provider CPower, Sunnova Manager, Grid Services Policy, Jamie Charles, Sunrun’s Rauscher and National Grid’s Tom.

VPPs can also benefit customers “through time-varying rates,” Tom added. And “flexibility markets could identify the timing and magnitude of a need created by local constraints and compensate aggregators for meeting that need while avoiding the cost of a traditional infrastructure solution,” he said.

State regulators will be central to resolving compensation issues, in approving cost recovery for technology investments and in setting compensation for customers that encourage participation, stakeholders agreed.

What regulators can do

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Order 2222 “opened the door for VPPs to compete” in organized markets, but work remains, DOE’s Shah acknowledged.

Order 2222 “started a good conversation,” said Sunrun’s Raucher. It could open wholesale markets “in the next decade,” and “be a lever for scaling VPPs,” but current regulatory efforts to further enable VPPs have “moved back to state regulators and utilities,” Rauscher added.

State regulators could streamline efforts to scale VPPs by proactively doing “jurisdiction-specific VPP market potential studies” and using them “to establish VPP procurement targets,” Brattle’s Hledik said. They could also make VPP pilots more viable with “innovative utility financial incentive mechanisms” and “updated existing policies,” he added.

Utilities can also help regulators understand “the need for foundational investments” to upgrade control rooms and communications with high-speed systems needed to scale VPPs, said Pepco Holdings’ Donohoo-Vallett. “Those expenditures will allow using the benefits of DER and VPPs for a more affordable energy transition,” he added.

Longer-term planning that identifies future market needs for load reductions or stability services enables VPP providers to build proactively to meet them and can also reduce costs, said CPower’s Sachs. Providers could then initiate expensive investments in technologies and customer acquisition and education where planners anticipate those needs and be ready to more quickly and cost-effectively offer system benefits to meet them, he added.

If the full VPP value stack at both the transmission and distribution system levels is recognized by planners, it is likely to show costs avoided by VPPs at scale make them “more cost effective than conventional resources,” Hertz-Shargel added.

Correction: We’ve updated this story to correct a quote inadvertently attributed to National Grid's Joshua Tom. We’ve further updated this story to better convey Tom's assessment of what's important to scale virtual power plants and National Grid's work on VPPs.