Electric utilities are developing a new understanding of how to plan for the increasing and worsening severe weather events like Hurricanes Milton and Helene.

The U.S. has experienced 24 events so far in 2024 “with losses exceeding $1 billion each,” and billion-dollar events have impacted all 50 states in the last decade, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported. There were 20.4 events per year from 2019 to 2023, but that jumped to 28 events in 2023 that cost $95.1 billion, NOAA added.

And, as Houston, Texas, customers of CenterPoint Energy learned earlier this year, many utilities have only begun resilience planning and preparation.

Hurricane Beryl’s “over a million customer outages” showed “there is plenty of need for the resiliency hardening investments that utilities such as CenterPoint have proposed,” Wei Du, a PA Consulting energy and utilities expert and former senior analyst and engineer for New York City’s Con Edison, told the New York Times after the event.

A well-planned, resilient system can better withstand severe weather, said Andrea Staid, principal technical leader, electric sector climate resilience, for research consultant Electric Power Research Institute. New climate modeling and asset performance metrics “can show which utility investments would make previously disruptive events go unnoticed,” she added.

EPRI, utilities and analysts remain uncertain, however, about which climate and asset performance metrics and methodologies are needed to most precisely identify power system vulnerabilities.

What’s a resilience plan?

New frameworks are emerging to guide utility resilience planning.

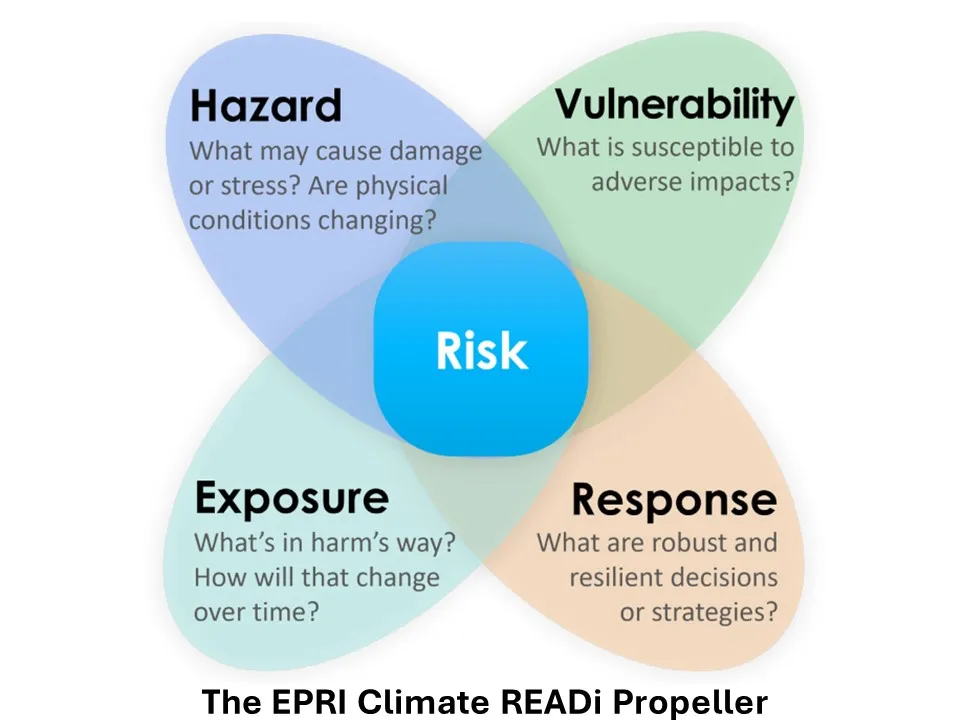

“The utility industry is shifting from responding to an individual event to mapping vulnerability to financial risk and quantifying benefits of potential investments on four pillars,” said Aditya Ranade, Guidehouse director of energy, sustainability, infrastructure.

“The first of the four pillars is hazard mapping,” which identifies types of threats, from flooding to wildfires, Ranade added. And “a multi-hazard benefit cost analysis approach is the next level of planning sophistication,” he said. The second pillar is a vulnerability assessment quantifying utility assets’ vulnerability to climate hazards, Ranade said.

“The third pillar is financial risk, which is the sum total of values derived in hazard mapping and vulnerability assessment,” Ranade said. And “the fourth pillar is decisions on adaptation measures, like replacing wood poles with composite poles, elevating substations against floods, or dynamic line ratings, and that is done by comparing benefits,” he added.

These pillars can help utilities optimize their investments, but the final decision on what spending to approve “is up to state policymakers or regulators,” Ranade said. “The compromise between resilience and keeping rates low is determined jurisdiction by jurisdiction, by state regulators and policymakers,” he added.

Though no two utilities face identical risks, assessment frameworks help utilities understand “the specific sets of risks they must mitigate,” said PA Consulting’s Wei Du. “Data analytics of the risks of different events, like storms and wildfires, and how to mitigate them, follow the same frameworks,” he added.

Specific planning mitigations include system hardening and technologies to bring situational awareness closer to real time, Wei said. Planning can also include proactively obtaining more and more granular local meteorology data to know what impacts might occur where and strengthening engineering standards and building codes to harden infrastructure, he added.

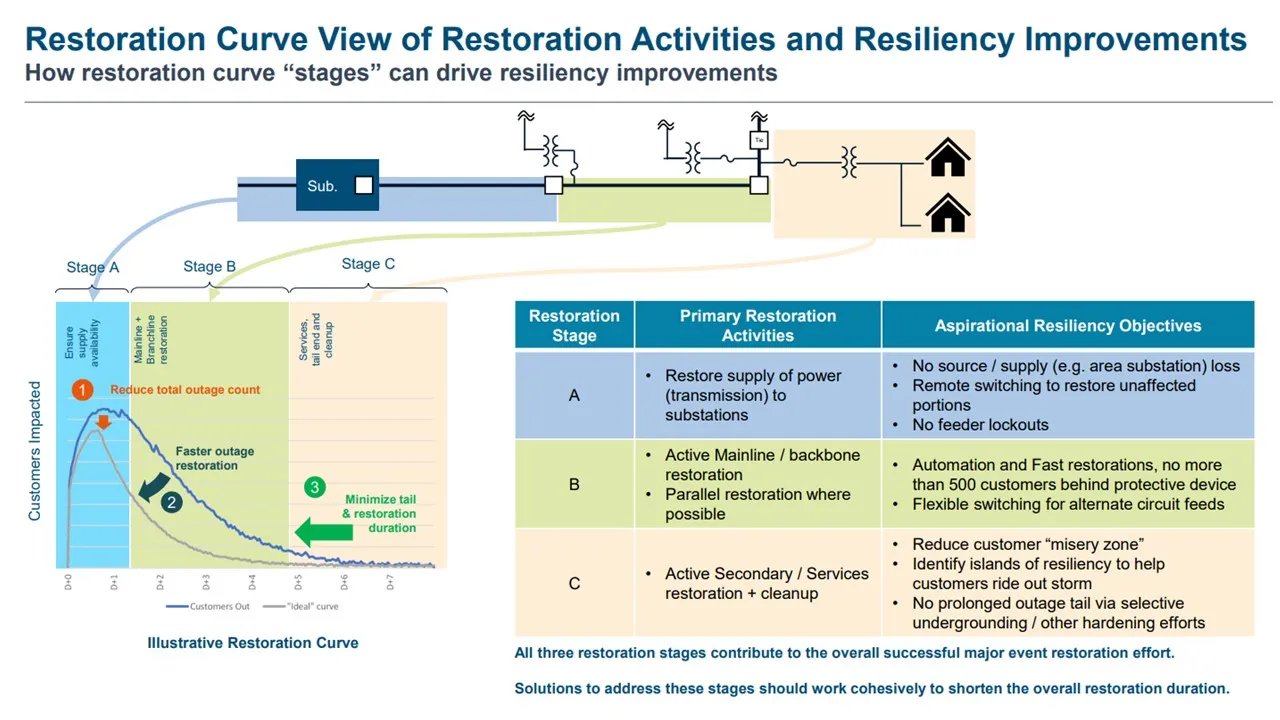

Utilities need to improve “restoration performance as demonstrated in the storm restoration curve,” Wei continued. The steeper the slope of the curve, the more people are restored in less time, and the more effective the utility’s restoration preparations were, he said.

“Best practices are emerging with four dimensions of response,” said Judsen Bruzgul, vice president, climate resilience and Climate Center senior fellow at global consulting and technology services provider ICF. “Some things can be hardened to withstand events, like undergrounding and strengthening poles,” and “some impacts can be absorbed,” he added.

But the only answer to some events is “limiting the impacts with faster responses because hardening would be too expensive,” Bruzgul continued. “The fourth dimension is investing in resources like microgrids that can sustain communities and customers,” and are adaptable enough “to continue meeting new challenges over time,” he said.

“Proactively investing in resilience is often more cost-effective than rebuilding after an event," Bruzgul added.

There are similar resilience planning frameworks with similar prioritized preparatory mitigations in new papers from the Edison Electric Institute and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. But EPRI’s still incomplete Climate Resilience and Adaptation Initiative, or Climate READi, may be the most anticipated assessment, several utilities agreed.

A framework to ensure “science-informed modeling” in climate resilience planning and decision making as the climate changes is not available, said EPRI’s Staid. But in 2025, Climate READi will provide “a comprehensive set of climate informed models to evaluate adaptation investments,” she added.

Climate READi will include definitive climate data and metrics, guidance on asset vulnerability, and power system planning for resilience, Staid said. Data-based comparisons of options like asset hardening, installing new assets, or operating the system differently allows prioritizing and justifying the best resilience investments, she added.

“READi will not add new metrics to traditional planning,” Staid said. But it will show where there is “resilience planning data on the increasing frequency and severity of extreme events that wouldn't typically show up in a resource planning model,” and allow “planning for combinations of climate hazards” that can enable handling “a diversity of region-specific or even system-specific conditions,” she added.

Some utilities will await EPRI’s 2025 framework. Others, already facing climate impacts, cannot.

Are utilities planning?

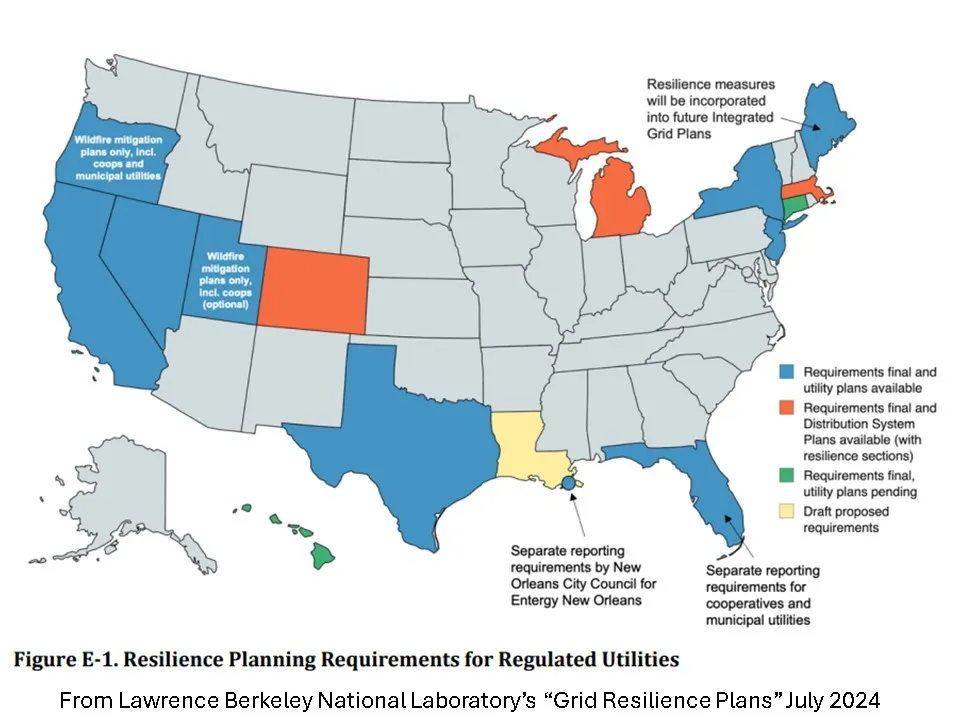

Regulators in 14 states, including California, Texas, Florida and New York, have resilience plan requirements for regulated utilities, according to a July study from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Through June, at least 30 utilities had filed resilience plans.

Best practices are emerging, and “just because there isn't a resilience plan requirement doesn't mean utilities aren't doing resilience planning,” said Lisa Schwartz, senior energy policy researcher and strategic advisor for LBNL’s Energy Markets and Policy Department and report co-author. But current utility resilience planning is limited, the research found.

There is not a clear connection between the identified hazards and the planning horizons of many resilience plans and how those lead to the plans’ vulnerability assessment, said Josh Schellenberg, the principal and chief operating officer of H&S Insights and an affiliate in LBNL’s Energy Markets and Policy department, and report co-author. “That makes it difficult to know how the proposed mitigations will impact the risks,” he added.

Feedback from five utilities showed the different attitudes on resilience planning. Some are waiting for EPRI’s Climate READi, some are moving ahead with their own planning tools and data, some are using tools and data from other researchers.

The Duke Energy utilities in Florida and the Carolinas are using advanced technologies, modeling and self-healing systems as part of “a multi-year grid improvement strategy,” according to Duke spokesperson Jeff Brooks. It is also developing “self-healing technology to isolate problems when they occur and restore power,” he said.

Across its territories, Duke spent over $4 billion in 2023 on hardening and modernizing its system and will spend “around $75 billion over the next 10 years,” Brooks continued. Recent rates “do reflect those improvements,” but the utility has worked to keep increases “predictable and gradual over time,” he added.

Central Hudson Gas and Electric followed requirements of New York law to develop its vulnerability study and a resilience plan which is now under regulatory review, according to Jennifer Paull, Central Hudson senior engineer, electric distribution, reliability, and resilience.

The resilience plan outlines improvements “to address current climate projections, the state of our system, and resilience services from 2025 through 2044,” Paull said. The funding request for 2025 to 2029 is about $28 million total, which represents an average annual rate increase of only 0.06% for customers, she added.

Future investments may be larger because storms are clearly increasing in frequency and magnitude, Paull continued. “There is not a widely accepted methodology for comparing resilience investments to avoided costs” on which to base spending proposals, though “industry initiatives, like EPRI’s Climate READi, may change that,” she said.

PacifiCorp utilities operate in states like Utah with resilience requirements and states like Washington without them. It plans to spend over $10 billion on reliability and resilience programs over the next 10 years, Josh Jones, PacifiCorp vice president of asset management and wildfire strategy, said. “We don’t take rate increases lightly,” but “we cannot ignore” the risks and impacts of climate events, he added.

Arizona has no state resiliency requirements, but Arizona Public Service incorporates resilience into its planning, Yessica Del Rincon, its spokesperson, said. The utility has been investing $2 billion annually on “understanding and mitigating risks,” to minimize or avoid service interruptions, she added.

Though Washington state does not have resiliency planning requirements for utilities, Puget Sound Energy is a participant in the three-year EPRI Climate READi initiative, said PSE’s Director, System Planning - Clean Energy Strategy & Planning David Landers. The utility remains focused on near term planning and awaits EPRI’s 2025 guidance because science-informed long-term climate impact forecasting “isn't there yet,” he added.

Three elusive factors

Better resilience metrics, estimates of resilience benefits, and benefit-cost analyses of resilience investments require further research, utilities, analysts and the LBNL researchers agree.

“There is no perfect way to optimize across all factors, but traditional benefit-cost analysis is one way to prioritize investments,” LBNL’s Schellenberg said. “Impacts from factors that can be quantified can help determine the resilience investments of best value,” he added.

“It can be difficult to quantify the benefits of resilience investments or justify the increase in rates that they may lead to” because the costs of not doing them is an unknown, Schellenberg continued. But further analyses “of the full range of benefits for multiple events over longer planning horizons may show benefits many times greater than the costs,” by “preventing catastrophic impacts,” he said.

“Rates are already getting higher,” LBNL’s Schwartz acknowledged. “But stakeholder engagement upfront can communicate the fact that it’s not just the dollars upfront, it’s the reduced storm impacts that matter, too,” she said.

Resilience plans may be part of integrated distribution system planning, and show “a holistic assessment of all investments that contribute to customer rates,” Schwartz continued. But “climate risks need to be assessed frequently, so commissions need to move forward on standalone plans, too,” she said. Central Hudson’s Paull agreed.

EPRI’s Climate READi calls for including climate metrics in all resilience planning decisions, “whether in standalone plans or as part of integrated system plans,” EPRI’s Staid said. Either way, “it will result in more science-informed results that can improve resilience decisions and performance,” she added.