Mike Hogan is a senior advisor at the Regulatory Assistance Project.

During the recent Winter Storm Elliott, a shockingly large amount of generation receiving capacity payments from PJM and ISO New England failed to perform when called upon. Nearly all of it was fossil-fueled, most of it fueled with natural gas. Under the pay-for-performance arrangements established years ago following a similarly dismal performance during 2014’s “Polar Vortex,” under which these generators have collected hundreds of millions of dollars a year to be reliable capacity, they face steep financial penalties for their failure to perform. Now some are seeking to evade those penalties, offering a flurry of excuses.

Regardless of the validity of any of the excuses offered (or lack thereof), these generators are also attempting to fall back on the stratagem behind which the fossil industry customarily retreats when caught with their pants down — claiming a threat to reliability, in this case from the possibility that the penalties might drive some generators into bankruptcy. At least two generators — Nautilus Power and Lincoln Power, both owned by Cogentrix — have filed for bankruptcy protection, and in a filing at FERC four fossil generation owners — LS Power, J-POWER, Rockland Capital and Earthrise Energy — claimed that bankrupting some of the non-performing generating companies “could have a significant effect on reliability and resiliency.”

Recent history demonstrates this tired grandstanding about reliability should receive no weight in considering their appeals (or in considering changes to the market rules). Why? Bankruptcy rarely leads to a loss of the associated capacity, in fact, quite the opposite: Generators with competitive operating costs (as these generators appear to have) that enter bankruptcy have every incentive to remain in business and to produce as much energy as they can whenever they can earn more than their variable costs. That is, such assets have value to the lenders as going concerns by allowing them to recover considerably more of their principal over time, compared to what they would realize in a liquidation. This is illustrated by a review of industry experience since the bursting of the merchant generation bubble in the early ‘aughts.

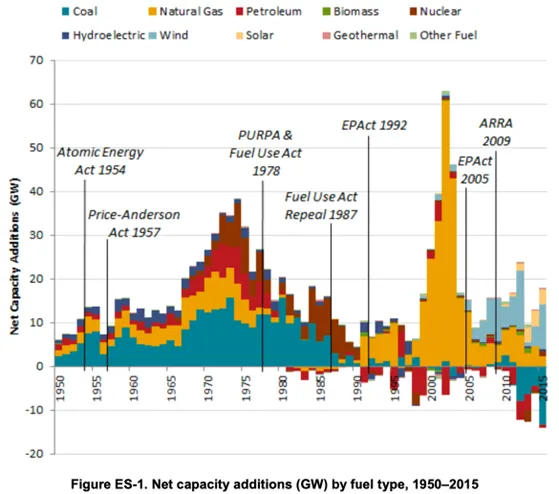

Between 1998 and 2005, over 200 GW (gross) of new capacity was added to the U.S. grid, overwhelmingly gas-fired CCGT, representing investment of approximately $250 billion. As demand flattened and financing costs rose, the boom turned into a bust that began with the Enron collapse in 2001 and accelerated in 2002. Most of that investment was “written off” by the original investors between then and 2006 — that is, the original investors sold at fire sale prices or surrendered their ownership rights to the lenders. The total value of ownership interests that suffered this fate was likely in the range of $150-200 billion.

The great majority of the investment was made by commercial enterprises, in most cases in ISO/RTO market regions. In very many of those cases, original owners were wiped out in bankruptcies, the primary lenders (first lienholders) took control, lenders whose security was “subordinated” to that of the primary lenders (second lienholders) accepted devalued equity in lieu of debt, and unsecured creditors (typically vendors of goods and services owed money) got stiffed. The plants themselves, in most cases, didn’t go anywhere. The primary lenders managed the assets as going concerns until such time as they could be sold for what lenders considered an acceptable exit value.

Two specific cases typify what happened across the industry. The first is a group of plants owned by US Gen, a leading domestic power plant developer. In the wake of the market collapse, US Gen went bankrupt. Among their assets were four plants — Millennium (in Massachusetts), Athens (in New York), Covert (in Michigan), and Harquahala (in Arizona), together nearly 4,000 MW of gas-fired CCGT — that had been financed as a single package of assets. Following US Gen’s bankruptcy, this group of assets was restructured in 2005 under a stand-alone company controlled by the primary lenders and subsequently went through multiple restructurings, including a second bankruptcy. All four plants are operational today and helping to meet resource adequacy needs in their respective markets.

The second case is that of the U.S. assets of InterGen, a leading developer of power plants globally that entered the booming U.S. market in the late 1990s. InterGen survived the bust thanks to a robust portfolio of international power projects, but the subsidiaries that owned their U.S. assets suffered a similar fate to US Gen. Wildflower owned two recently commissioned peaking plants in California representing 225 MW of capacity. Four large plants were in various stages of completion at the time — Cottonwood (in Texas), Magnolia (in Mississippi), Redbud (in Oklahoma) and Sequoia (in California), together nearly 5,000 MW of gas-fired CCGT. These plants were surrendered to their lenders in the subsequent bust, wiping out InterGen’s equity and requiring second lienholders and unsecured creditors to swap debt for equity and/or walk away.

Each of these assets were managed by their primary lenders as going concerns until they could be sold and at least most of the original debt recovered. All of these plants were completed and are operating today (Sequoia now operates as Mountainview) and, as with the US Gen assets, helping to meet resource adequacy needs in their respective markets.

This is not to suggest these events were something to be desired. Investors lost money, lenders suffered losses, vendors went unpaid and people lost jobs. But the market worked — demand continued to grow, prices were stable, and reliability of service and resource adequacy never suffered. In fact, in both cases, the new owners of some of the plants have invested in expansions to the original capacity.

The big winners? Consumers. Unlike in previous boom-bust cycles in the electric utility industry — most notably the over-investment that occurred through the 1970s principally in nuclear and coal generation, the costs of which were borne by captive utility customers — electricity customers were largely spared the risks and attendant costs of the market-based investment boom of the late 1990s. Moreover, the bankrupted generating capacity largely remained on the grid after being sold at deeply discounted prices, meaning the wave of restructurings never actually compromised reliability. As demand gradually increased and older, dirtier oil- and coal-fired generation retired, these “failed” gas-fired CCGT plants were able to increase their output, serve consumer demand and recover enough market value to allow their lenders to recover a significant portion of the original debt.

It is likely that this process would have played out with the merchant generating plants in any case. A strikingly similar scenario played out in the fiber optics industry beginning with the tech and telecoms busts in the late 1990s. But because of similarly voiced concerns that a disorganized wave of plant withdrawals from the organized markets might threaten reliability, it was at that time that some of the ISO/RTOs (notably ISO New England and PJM) adopted forward capacity markets (FCMs), central auctions to set the clearing price at which the required quantity of generation capacity would commit to operate as reliable capacity for a set period in the future.

Those FCMs still exist — they are the source of the hundreds of millions of dollars a year these generators have been paid to perform when called upon. They have been continuously refined and amended to improve their effectiveness in achieving their original purpose of retaining adequate capacity to ensure reliability (including the adoption of the pay-for-performance bonuses and penalties described above). While the FCMs are the subject of various ongoing debates relating to other matters, there is no reason to expect them to be any less effective at retaining needed capacity today, even in the face of possible generator bankruptcies, than they were at their inception.