Dive Brief:

- A 69-year-old Nuclear Regulatory Commission rule underpinning U.S. nuclear reactor licensing exceeds the agency’s statutory authority and creates an unreasonable burden for microreactor developers, the states of Texas and Utah and advanced nuclear technology company Last Energy said in a lawsuit filed Dec. 30 in federal court in Texas.

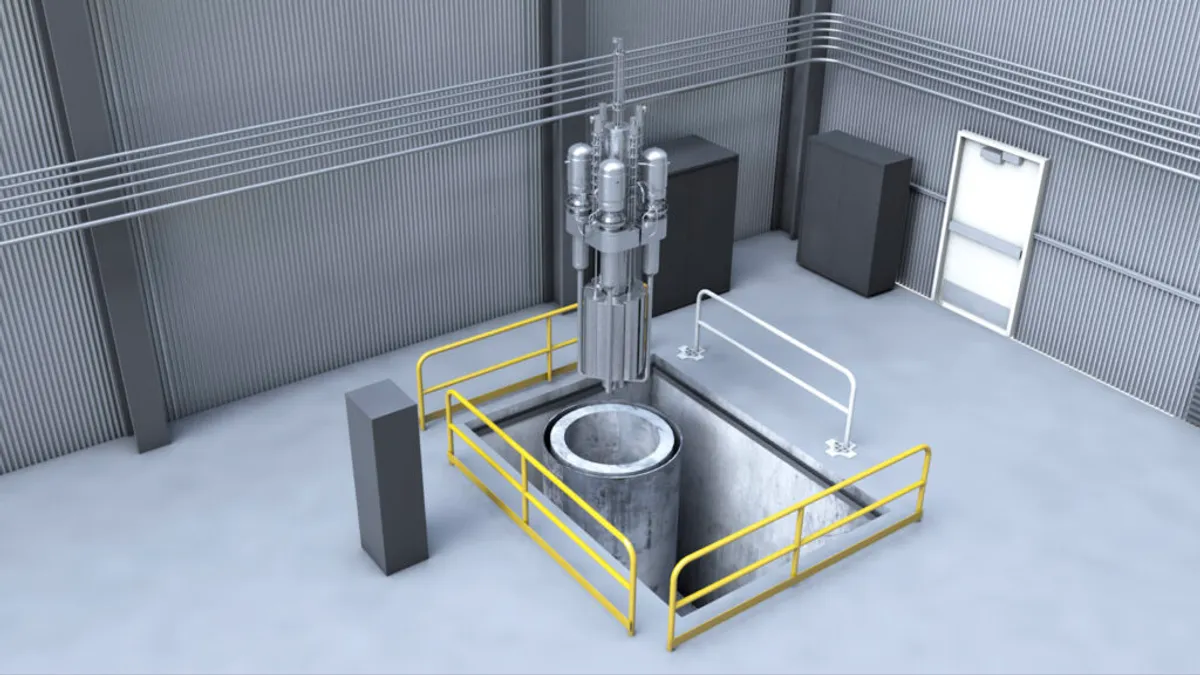

- The plaintiffs asked the Eastern District of Texas court to exempt Last Energy’s 20-MW reactor design and research reactors located in the plaintiff states from the NRC’s definition of nuclear “utilization facilities,” which subjects all U.S. commercial and research reactors to strict regulatory scrutiny, and order the NRC to develop a more flexible definition for use in future licensing proceedings.

- Regardless of its merits, the lawsuit underscores the need for “continued discussion around proportional regulatory requirements … that align with the hazards of the reactor and correspond to a safety case,” said Patrick White, research director at the Nuclear Innovation Alliance.

Dive Insight:

Only three commercial nuclear reactors have been built in the United States in the past 28 years, and none are presently under construction, according to a World Nuclear Association tracker cited in the lawsuit.

“Building a new commercial reactor of any size in the United States has become virtually impossible,” the plaintiffs said. “The root cause is not lack of demand or technology — but rather the [NRC], which, despite its name, does not really regulate new nuclear reactor construction so much as ensure that it almost never happens.”

More than a dozen advanced nuclear technology developers have engaged the NRC in pre-application activities, which the agency says help standardize the content of advanced reactor applications and expedite NRC review. Last Energy is not among them.

The pre-application process can itself stretch for years and must be followed by a formal application that can take two years or longer for the agency to evaluate.

Bill Gates-backed TerraPower began non-nuclear construction activities in June at the Wyoming site of its planned 345-MW commercial demonstration reactor, but an NRC timeline suggests a decision on its nuclear construction permit application will not come until 2026 at the earliest. Since December 2023, the agency has cleared Kairos Power to build two low-power, grid-connected test reactor facilities in Tennessee. In September, it approved Abilene Christian University’s construction permit application to build a 1-MW research microreactor.

The NRC misinterprets its authorization under the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 to regulate reactors “capable of making use of special nuclear material in such quantity as to be of significance to the common defense and security, or in such manner as to affect the health and safety of the public,” Texas, Utah and Last Energy argued in the Dec. 30 complaint. The states’ research reactors and Last Energy’s design, which “has no credible mode of radioactive release even in the worst reasonable scenario,” do not meet that definition, they said.

Rather than engage with the NRC, Last Energy has focused on developing reactors abroad “in order to access alternative regulatory frameworks that incorporate a de minimis standard for nuclear power permitting,” the plaintiffs said. Last Energy has development agreements for more than 50 nuclear reactor facilities in Europe, it said, including a $400 million project at a former coal power plant in Wales that could come online in 2027.

Reactors exempt from the NRC’s utilization facility rule would still be subject to “stringent [NRC] oversight of the special nuclear material that fuels reactors, not to mention state regulation, export controls, restrictions on nuclear weapons production, and prohibitions on weapons-grade nuclear material,” as well as state regulation of power generation, the plaintiffs said.

The NRC’s Part 53 rulemaking process recognizes the need for proportional, performance-based regulation to accommodate a wider range of technologies, including the non-light-water designs Last Energy and other advanced reactor developers are pursuing, White said. The final Part 53 rule is expected by 2027, the NRC says.

“The completion of Part 53 could potentially move us toward this idea of a more scaled regulatory framework for advanced nuclear reactors,” White said.

The NRC is in the early stages of a separate process to streamline licensing of microreactors smaller than 20 MW. The bipartisan ADVANCE Act also requires the NRC to evaluate combined license applications for new reactors within 25 months of the application date and make other reforms to improve licensing efficiency. That could ultimately shorten “subsequent custom combined license” applications to as little as six to 18 months, advanced reactor developer Oklo said in an August shareholder letter.

Though the NRC is pursuing “a larger constellation of activities that are going to apply to these smaller reactors … that allow them to be deployed rapidly with safety features,” further Congressional action or a new NRC rulemaking would be needed to address the specific issues raised in the Dec. 30 lawsuit, White said.

But the suit “demonstrates the level of interest from states and developers about how we get nuclear technology quickly on the market,” White said. “I can’t imagine this happening 10 or 15 years ago.”

Last Energy said it was unable to provide comment by press time.

Correction: A previous version of this story had an incorrect description of Kairos Power’s upcoming test reactor facilities in Tennessee. They will be connected to the grid.