Nick Guidi is a senior attorney with the Southern Enviromental Law Center. . Chris Carmody is the Executive Director of the Carolinas Clean Energy Business Association.

Last November, regional utilities launched the Southeast Energy Exchange Market, or SEEM, with great fanfare. They promised a competitive market that would bring consumers across the Southeast greener energy at lower cost, despite protests that SEEM’s design was unlawfully discriminatory and unlikely to produce the claimed benefits. Over the past year SEEM’s poor performance has proven its critics right and demonstrated that the energy trading platform is in dire need of a substantial overhaul — and a more ambitious design — if it is to be either lawful or beneficial.

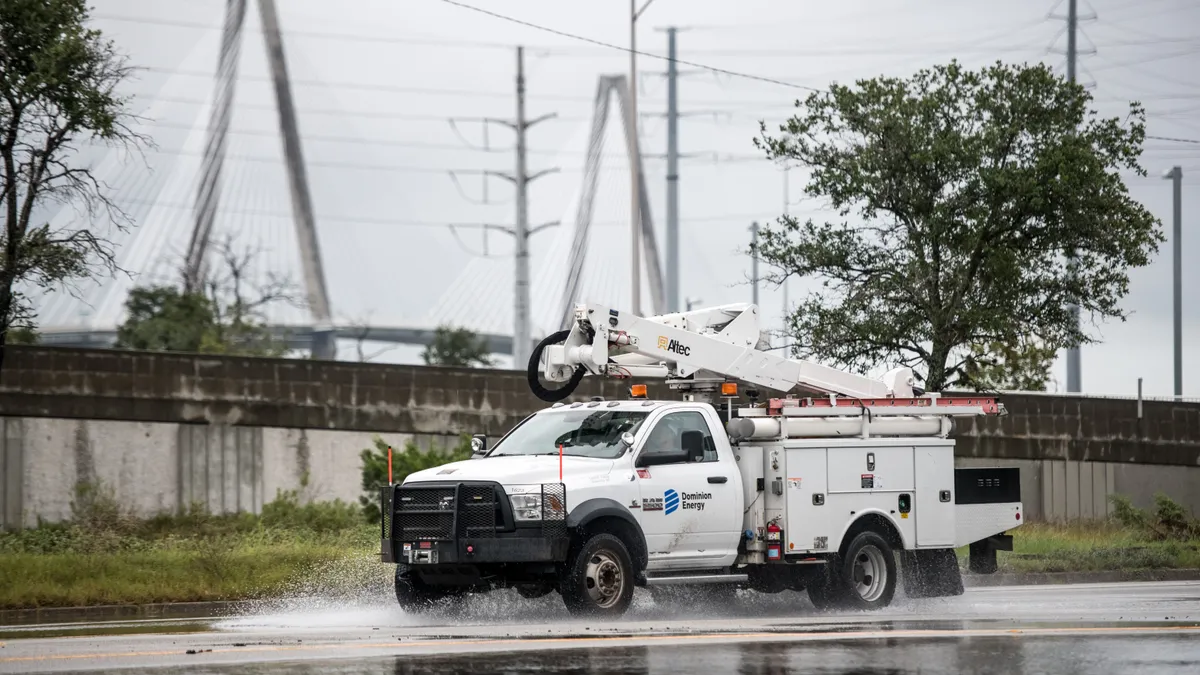

SEEM was created and is governed by the largest monopoly utilities in the region, including Southern Company, Duke Energy, Dominion Energy South Carolina and the Tennessee Valley Authority. Billed as an effort to streamline and modernize the region’s antiquated bilateral trading practices, SEEM promises participants exclusive access to lucrative trading opportunities and free transmission service across the Southeast. But SEEM imposes significant barriers to participation, excluding producers from neighboring regions and certain types of resources, such as demand response and distributed energy like rooftop solar.

The first truly regional marketplace in the Southeast should have had great potential, but its discriminatory mechanisms instead allow monopoly utilities to maintain control over the market and thwart competition from independent sources of clean energy.

Unsurprisingly, SEEM’s foundational design flaws have severely limited its effectiveness. In proposing the market, SEEM utilities predicted it would reap $37 million to $46 million in benefits in its first year, over its entire ten-state footprint. And they claimed that it would provide significant support for renewable energy integration, estimating that benefits during the daytime (i.e., solar hours) would nearly double benefits during other hours. SEEM has fallen woefully short on both fronts.

After nearly one full operating year, SEEM has realized only $3.3 million in total benefits, less than a tenth of SEEM utilities’ low-end projections. Indeed, these benefits have barely eclipsed SEEM’s levelized annual operating costs. This is due in large part to the platform’s minimal trading activity. SEEM estimated an average hourly trade volume of 1,323 MWh yet has seen an average of only 72 MWh in hourly activity through its first year of operations, as just a small fraction of its bids and offers create matches.

There is no evidence that SEEM is actually advancing renewable integration. SEEM does not report the fraction of trades that involve renewable resources. But independent power producers — which, in the Southeast, are largely solar facilities — have not participated in any SEEM trades. And the minimal publicly available trading data does not show overall benefits during solar hours exceeding non-solar hours, certainly not double the non-solar hour benefits projected by the SEEM utilities. While SEEM proponents mused that the “largest risk to [SEEM] benefits” is “limited participation,” that risk has become a painful reality.

In addition to limiting both its monetary and renewable energy benefits, SEEM’s exclusivity has also created legal problems. This summer, the D.C. Circuit vacated the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s approval of SEEM, finding that improperly restricting SEEM’s free transmission service to entities located within the SEEM footprint and failing to establish a non-discriminatory, market-wide tariff, violates core FERC requirements.

The court’s concerns have borne out in practice, as the list of SEEM market participants still includes only utilities. No independent power producers have engaged in SEEM trades to this point, further underscoring the lack of market competition. Indeed, the SEEM auditor’s monthly reports routinely note that one or two unnamed utilities dominate the majority of trading activity each month, lending credence to the court’s concern that SEEM is neither open nor particularly competitive.

Months before the court weighed in, the problems with SEEM’s market design were already apparent. Last December, Winter Storm Elliott caused multiple SEEM utilities to order rolling blackouts, leaving hundreds of thousands of customers in the dark during one of the coldest stretches in recent memory. Between December 24 and 26, SEEM went dark as well, recording no trades during this three-day period. Simultaneously, neighboring grid operators SPP and MISO, whose territories border SEEM member utilities, curtailed substantial amounts of wind energy. Just outside SEEM’s footprint, that wasted wind energy was prohibited from the SEEM marketplace while the Southeast sustained debilitating energy shortages.

But all is not lost. Following the D.C. Circuit’s order, FERC has the power to condition SEEM’s continued existence upon certain, much-needed changes. Acknowledging SEEM’s distinct power pool attributes, FERC should first require a nondiscriminatory market-wide tariff with open transmission access for all resources to ensure that no arbitrary eligibility criteria prevent any willing participants from trading in the market. Second, expanding access to entities located outside the SEEM footprint will increase reliability and trading volume, which can help bring actual benefits closer to the original estimates. Third, FERC should require additional transparency into and monitoring of SEEM’s trading activity to ensure trading within SEEM occurs in a fair and fully competitive manner. Finally, FERC should require that SEEM allow non-utilities to become full members who can ensure that design, governance and operation of the market actually serves the needs of all of its participants.

These changes are common sense. Ultimately, however, SEEM’s current design ensures that its most hopeful estimates will remain a small fraction of the benefits currently realized by consumers living in regions with truly competitive markets.

As the first organized market to cover most of the Southeast, SEEM has already brought together the region’s load-serving entities into one coordinated whole. But to truly capitalize on this effort, SEEM must be designed by and for all participants. At a minimum, SEEM should expand trading functionality to encompass all real-time operations, like the energy imbalance markets operating in the West. These successful markets generate benefits that dwarf SEEM’s, and FERC has found that such markets improve systemwide reliability.

If the SEEM utilities sincerely seek to reduce costs for customers, increase opportunities for renewable energy, and shore up the regional grid’s reliability in the face of increasingly severe weather, they should emulate the successful examples of inclusive energy markets in the West. Continuing on the current course will only leave customers regionwide at the mercy of more extreme weather, with higher energy costs. Without significant reform, it may also guarantee that SEEM does not see a second birthday.