Dive Brief:

-

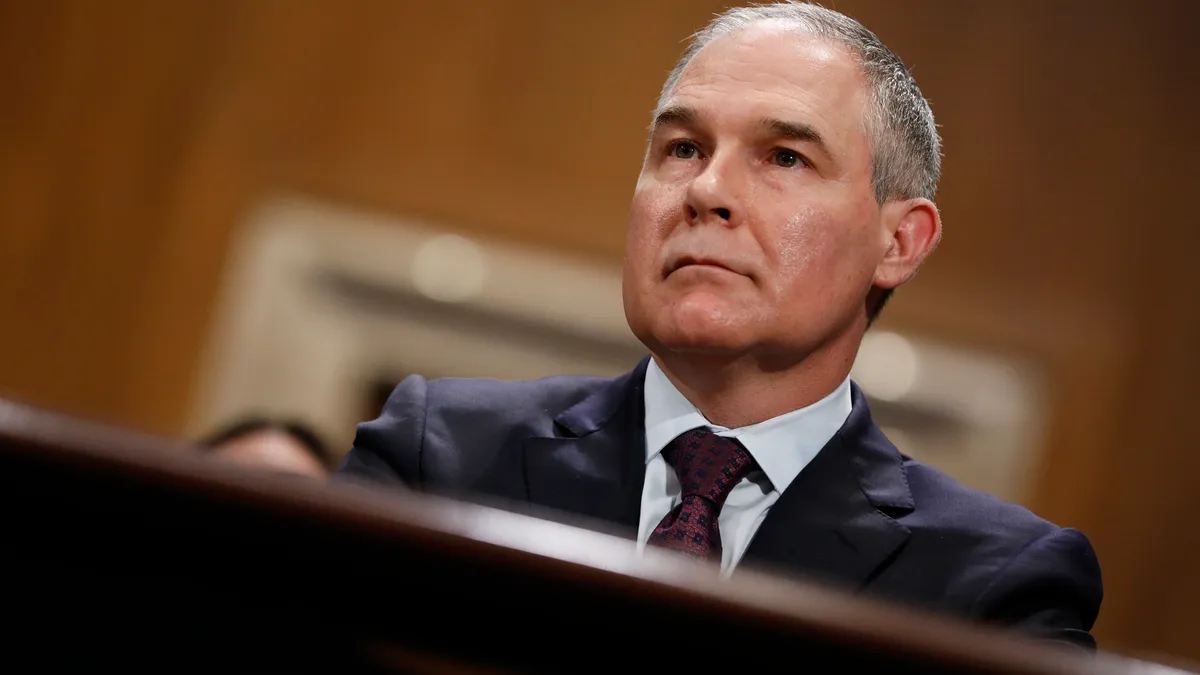

EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt on Thursday released a memo outlining changes to the EPA's review process for the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS), a rule that covers criteria pollutants that contribute to ground-level smog.

-

The EPA administrator said the new "back to basics" approach will reform the NAAQS review "in a manner consistent with cooperative federalism and the rule of law," but critics said it would allow the agency to diminish the input of human health science in reviewing the standards.

-

The EPA memo is part of a four-pronged strategy to weaken air regulations, UCLA Professor Sean Hecht said, which includes limiting the types of science EPA may consider, putting industry advocates on scientific advisory committees, "stacking" comment records with "irrelevant" arguments, and framing key rulemaking decisions as discretionary policy judgments.

Dive Insight:

The EPA's NAAQS standards, first enacted in 1990, cover smog-causing pollutants like ozone and nitrogen oxides that can cause respiratory problems, particularly in vulnerable populations.

In 2015, the EPA set the standard for ground-level ozone, one of the most common criteria pollutants, at 70 parts per billion (ppb), a standard at the lenient-end of the range recommended by EPA's scientific advisory committee.

The standards must be reviewed every five years, and Pruitt's Thursday memo aims to preempt that process with reforms to the EPA's procedures.

"These NAAQS process reforms better separate scientific judgments from policy decisions," Marcus Peacock, a former EPA Deputy Administrator in the George W. Bush administration, said in a release. "Setting air quality standards is murky enough without muddying the distinctly different duties of scientists and political appointees in protecting human health and the environment."

But environmentalists and some energy lawyers say the changes are aimed at doing exactly the opposite — replacing EPA's process of using health-based science to set air quality standards with one that also includes economic considerations, like cost.

Under the Clean Air Act, the EPA is supposed to set NAAQS standards based solely on human health impacts, said Sean Hecht, co-executive director of the Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the University of California-Los Angeles.

But in this memo, Hecht says the administrator attempts to change that policy, directing its Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee (CASAC) to consider "any adverse public health, welfare, social, economic, or energy effects" of setting new standards.

"[The memo is] trying to make the case that [non-health impacts] are something that EPA should be taking into account when it is setting the standards," Hecht said, "but I think the statute is quite clear that advice is about strategies about attainment and maintenance of the standards, which is very different than what EPA takes into account when it does the rulemaking, when it sets the standards."

Pruitt's memo repeatedly cites a 2001 Supreme Court case, Whitman vs. American Trucking Assn., as justification for the change. But Hecht said the administrator is taking the decision out of context, and it actually prevents the type of reform his memo envisions.

"The court made the same distinction. [The EPA] sets the standards, the standards are health-based. When they figure out strategies for meeting the standards, there are a lot of other things they can do," he said. "This memo tries to blur that line by asserting that this statute gives EPA the authority or even the mandate to consider this type of information in the standard-setting process."

Environmentalists piled on the administrator's legal rationale as well. John Walke, clean air director at the NRDC, pointed out on Twitter that Justice Antonin Scalia wrote the decision for a unanimous court that the Clean Air Act "unambiguously bars consideration of the economic consequences of MEETING clean air health standards during the process of SETTING those standards,"

"@EPAScottPruitt is desperate to consider these consequences during the health standard-setting process, to facilitate weakening today's health standards (for ozone & soot) so they are more affordable to industry — and unsafe," he wrote.

Hecht said Pruitt's move aligns with an emerging strategy at the EPA to weaken clean air protections from within.

The first step, he said, is to limit the type of science EPA may consider by barring human health studies that formed the basis of many current clean air standards. The administrator took that step last month with his so-called "secret science" rule.

Second, the EPA will move to increase industry input on its scientific advisory boards, internally influential review bodies that recommend health-based standards. Pruitt last year blocked scientists receiving EPA funding from those boards, allowing industry-backed scientists more participation.

Third, Hecht said, is to "stack the record" for health-based standards "with irrelevant economic arguments" that Pruitt can point to when weakening regulations.

"The court has said these aren't relevant but that doesn't mean someone can't make comments in the record about it," Hecht said, "but it's not something the advisory board is supposed to be doing as it sets standards."

Finally, Hecht said the administrator would seek to frame major regulatory shifts as "discretionary policy judgments, which is embedded in this memo."

"Realistically the administrator has to be able to exercise some judgment in figuring out the right methodology for interpreting this statutory command," Hecht said. "I think what Pruitt is trying to do in this memo and other places is say there's a whole bunch of stuff that people might have started thinking about as scientific judgments and we are now going to start thinking about them as policy judgments."

"If they're policy judgments the administrator has a lot of discretion on how to implement them," he said.