Robin Gaster is president of Incumetrics and a visiting scholar at George Washington University. He serves as a nonresident senior fellow at ITIF’s Center for Clean Energy Innovation.

As the climate changes around us, the case for green tech gets stronger by the day. But the drivers that accelerated every transformative innovation since the industrial revolution won’t work for green tech. Previous technology revolutions have all come with massive performance advantages. But the green energy revolution won’t be like that. Instead, it must be driven by price.

We have since the 1850’s enjoyed an extraordinary string of extraordinary technological innovations, from the steam engine to the smartphone. It’s a long and very distinguished list: railways, autos and airplanes; refrigerators and washing machines; TVs, telecommunications and the Internet… In each case, these new technologies fundamentally changed how we live, leaving marks that are still visible everywhere we look.

Green energy is nothing like that. It is not seeking to open a portal into a new experience or a new capability. It will not let us broadcast moving pictures, fly across distances that represented weeks or months of hard travel, or allow us to talk to our friends in Australia. It won’t make summers more bearable, or give us mechanical legs to traverse distances that were for millennia unimaginable. Green energy is not a visible performance improvement in any way.

Of course, not poisoning the planet with invisible emissions and helping avoid the worst impacts of global warming and climate change are profound performance improvements. But none of that is immediately tangible. So green tech has no built-in magnet for adoption, no new capability that leads us to say, I want that. I want to be able to fly or drive or watch TV or Zoom.

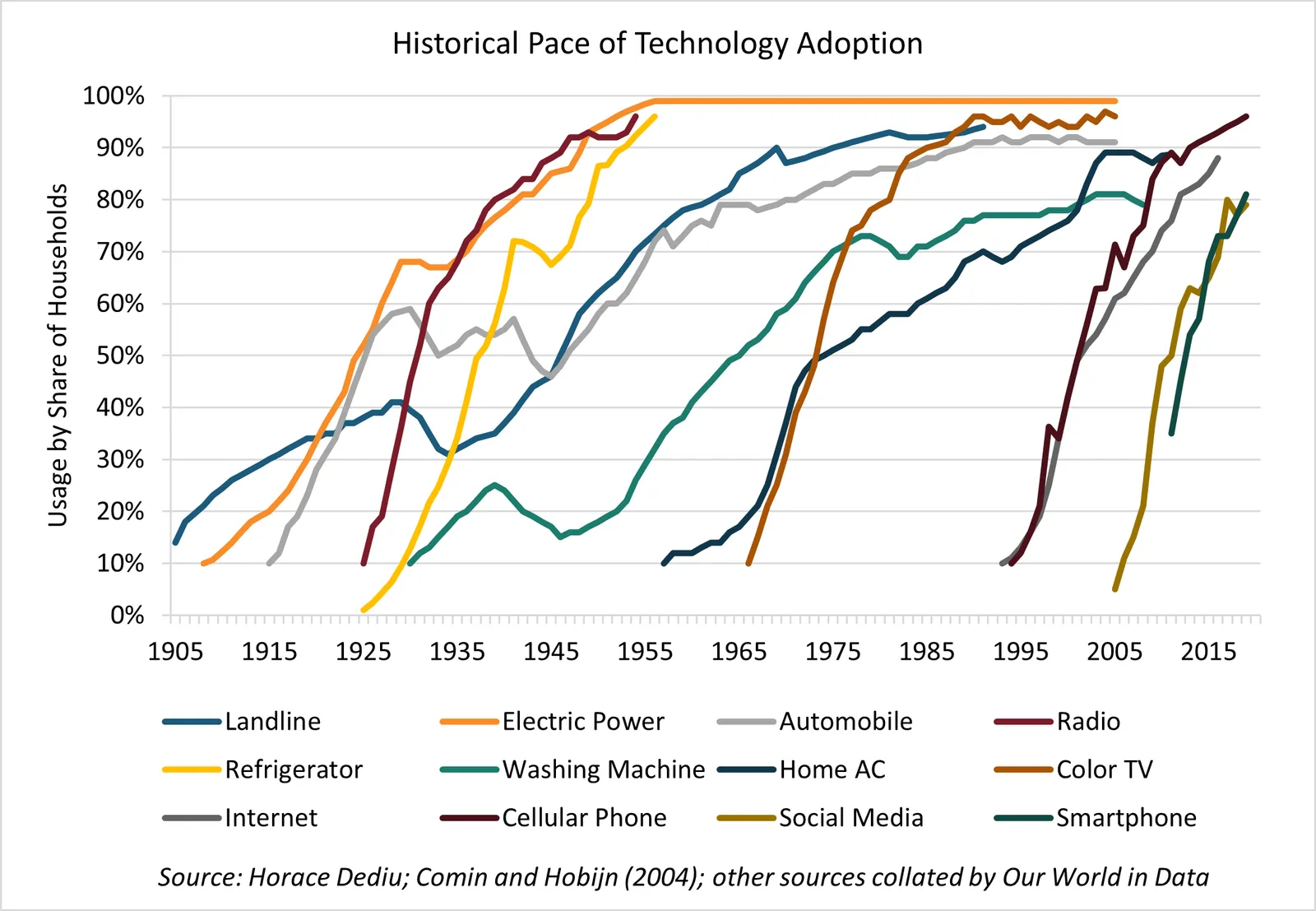

All new technology follows an adoption curve: Initial interest comes from early adopters who like to experiment, like to be ahead of the curve. If the new tech is successful, it gradually edges into the mainstream. Then costs fall rapidly, as prototypes are followed by batch production, then full mass production, which drives economies of scale. Falling prices attract more users, and mass adoption begins. Finally, even the laggards adopt; almost everyone has a smartphone now.

Every major technology has followed that curve (see chart). Note that the pace of adoption is accelerating: The landline took almost 90 years to reach 90% adoption; the cell phone took just 20.

If the green energy revolution is not to be driven by obvious tangible performance advantages, adoption must be driven by something else. Many environmentalists hope that we can be shamed into going green: Don’t drive, don’t fly, go vegan and eat locally produced food, turn off the A/C, don’t have kids, etc. But this just won’t work. Not a single government has been elected on a platform of less. Air traffic is booming, A/C use is growing rapidly as the climate heats up, cars remain the central mode of household mobility. Vegans and locavores are barely a fringe.

Further, climate change is global and requires global solutions. Low-income countries will drive emissions as they industrialize, urbanize and electrify. Their governments (and their people) aspire to first-world lifestyles. They want to be rich enough to own a car, fly, eat meat, enjoy A/C at home. And who can blame them?

Maybe we can subsidize our way to green, if we offer big enough subsidies. Norway is rapidly becoming all-electric for vehicles on the back of massive subsidies. Norway is rich enough and small enough: about 5 million people and a GDP per capita of $89,000. But India has 1.3 billion people and a GDP per capita of $2,200. Massive subsidies for green energy are simply out of reach there.

Regulation and energy taxes are similar, another way to reallocate transition costs. But the U.S. for example won’t bite that bullet — the last serious attempt at a carbon tax was more than a decade ago. Low-income countries won’t either.

So going green requires the use of price levers. If there is no tangible performance advantage to green adoption turns on price. Thus green tech must reach and exceed price/performance parity, or P3, with dirty tech. Performance must match — 24/7 access to energy for example — but at a price that’s at least equivalent. That’s the bottom line: when green tech reaches P3, markets will take over and green tech will accelerate up the adoption curve.

Unfortunately, many technologies are not on a path to P3. Blue hydrogen will never reach P3 with dirty hydrogen; it simply adds an (expensive) step to existing production. Green aviation fuels from biomass will never scale. Spending scarce time and resources on these technologies is a bad mistake.

So governments have two jobs: accelerating movement down the cost curve for technologies that can reach P3, using a full toolkit that can include targeted subsidies, procurement, and supply chain support, for example; and pouring in additional research funding to go beyond technologies that won’t. Here we must find high risk/high reward projects that are not yet supported by the private sector. We are going to need many of them, as soon as possible.