David Pomerantz is the executive director of the Energy and Policy Institute.

Larry Householder, the former Ohio Speaker of the House, entered a courtroom last week where he’s being tried for his alleged role in a brazen $60 million bribery scheme involving the investor-owned utility FirstEnergy. It’s the largest political corruption case in Ohio’s history.

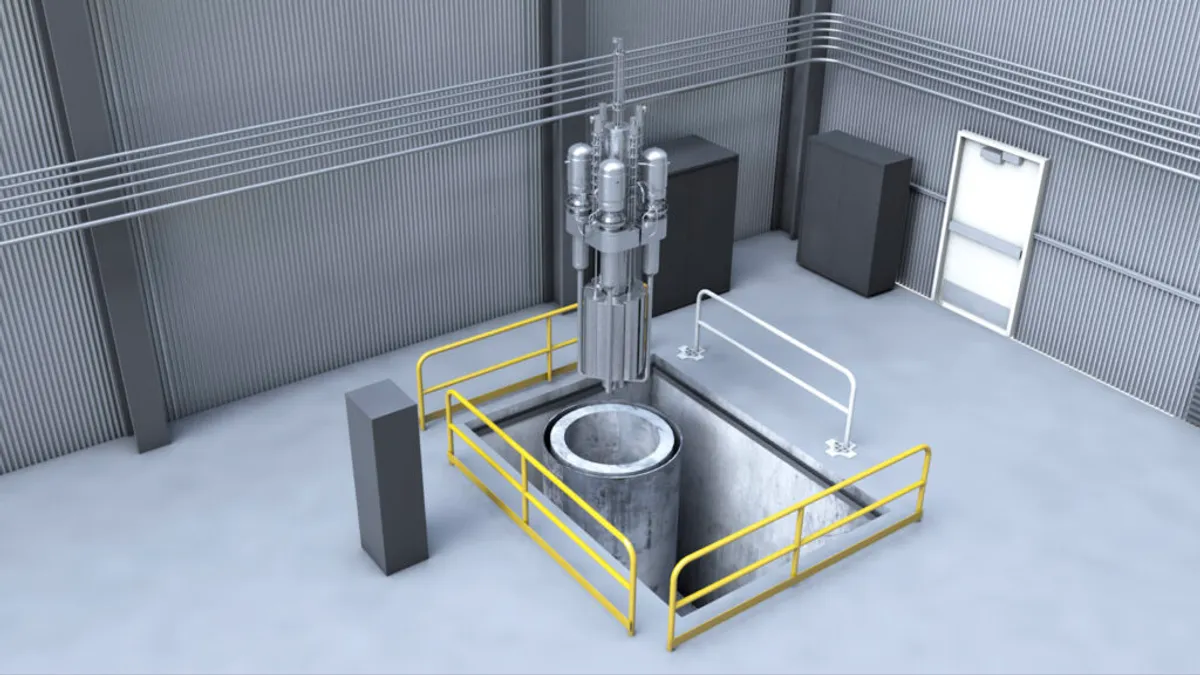

Prosecutors allege that FirstEnergy funneled money through dark money groups to Householder’s political organization in exchange for a bailout of several of the company’s unprofitable nuclear and coal plants that cost ratepayers over $1 billion.

Based on audits by regulators, it’s clear that at least part of the money Householder received came from fees that FirstEnergy collected from ratepayers, likely across many states, through their monthly bills.

Unfortunately, utilities charging customers for many of the costs of their sprawling political influence machines is standard operating procedure across the industry.

While some cases have led to high-profile criminal charges and indictments, utilities regularly exploit a host of more mundane legal loopholes to use customers’ money to try to influence politicians and regulators, all in an effort to grow their profits and thwart competition.

For example, gas utilities use their trade associations to convince people that methane isn’t a threat to our climate, and electric utilities use customers’ money to fund slick PR campaigns against rooftop solar, or to convince people that rate increases are good for them.

Customers pay first for the political influence tactics, and then again via the higher rates and environmental harm that flow from them.

Ratepayers deserve better.

State and federal policymakers can ensure that no ratepayers ever have to pay for a situation like the FirstEnergy-Householder corruption scheme again.

To do so, they should adopt a mix of rules, disclosure and enforcement.

For starters, public utility commissions, or PUCs, which regulate investor-owned utilities in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, should explicitly bar utilities from spending customers' money on politics, using clear and common-sense definitions of political activity.

Rules are hard to enforce without transparency, so it’s also critical that PUCs require detailed disclosure of all utility political expenses.

Finally, when utilities violate these rules, PUCs must levy fines and penalties that extend beyond refunds. If the only consequence of being caught breaking the rules is that a utility has to refund customers without penalty, it would be as if every time the police stopped a bank robbery, they simply asked the robber to return the money to the vault, and then walk away otherwise unpunished.

Public utility commissioners aren’t the only state leaders who can and should take action to prevent the next FirstEnergy scandal from coming to their state.

State law governs the regulatory authority and responsibilities of each public utility commission, providing legislators with the ability to write or amend statutes requiring PUCs to take many of the above actions in rulemaking, disclosure and enforcement.

Legislation can remove uncertainty, place an affirmative onus on PUCs to act, and guarantee continuity in the face of new PUC appointments or elections. Legislators can also appropriately budget PUCs to enable better oversight and enforcement, and can craft tighter campaign finance rules for utilities.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission also has tools at its disposal to protect ratepayers.

FERC sets the rates for all interstate transmission of electricity and gas, which means that FERC has jurisdiction over what costs utilities are allowed to recover from their wholesale transmission customers.

FERC also manages the Uniform System of Accounts, or USoA, which gives guidance to utilities for how to classify different expenditures. Most state PUCs require utilities to use the USoA as their accounting system, which means that the accounting system has a trickle-down effect beyond FERC’s jurisdiction over wholesale transmission rates.

FERC has long recognized that ratepayers should not be forced to pay for their utility’s political activities, which typically benefit a utility’s shareholders. Yet despite that principle, the nation’s ratepayers are currently paying for their utilities’ efforts to influence policy in the transmission portion of their gas and electric bills.

FERC issued a Notice of Inquiry in 2021 to consider many questions related to utilities’ recovery of political costs from customers. In response, consumer advocates and state officials alike called on FERC to clarify rules, definitions and standards to make explicit that utilities should not be able to charge ratepayers for a broad suite of political influence activities.

The agency can act with a proposed set of new rules at any time.

Enacting these reforms will result in lower bills for the nation’s energy customers. It will make addressing climate change easier, as utilities’ ratepayer-subsidized political operations often oppose climate action. It will strengthen our democratic institutions, by reducing the ability of some of the most aggressive spenders on politics to do so under cover of darkness.

State and federal leaders should act now for all these reasons, and to prevent the next trial of a ratepayer-funded corruption scheme from landing in their state next.