David Schlissel is the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis director of resource planning analysis.

NuScale Power is hoping to be among the first of about a dozen companies trying to take advantage of the much-hyped market for small modular nuclear reactors, or SMR. So far, however, the Oregon-based company is looking like the first canary in the coal mine.

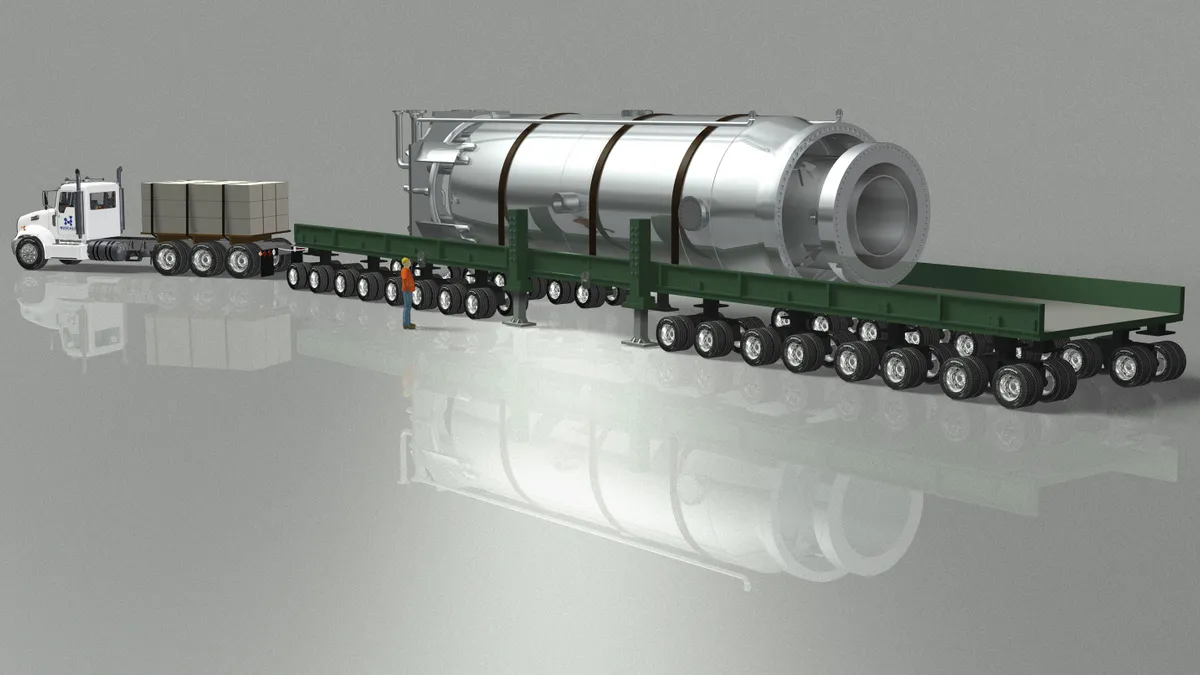

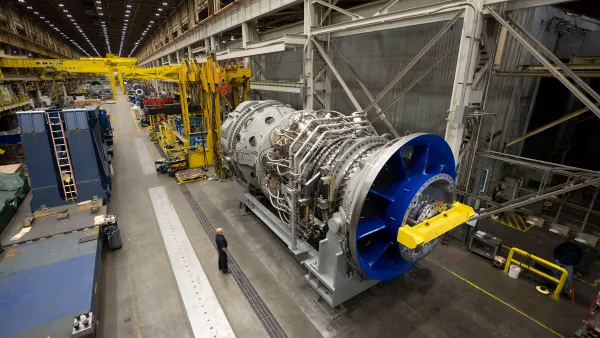

Considered a leader in the new technology, NuScale is marketing its SMR project by claiming that the reactor design project will save time and money — persistent problems for traditional large nuclear plants.

But NuScale and the Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems, its partner in an SMR project planned for Idaho, announced early in January that the target price for the power from their proposed modular reactor had risen by 53%, from $58/MWh to $89/MWh. The companies said higher interest rates and inflation had pushed the costs of building the proposed reactor from $5.3 billion to $9.3 billion.

The announcement has serious implications for all would-be SMR manufacturers.

Although there may be significant differences among the various SMR designs, they all rely on essentially the same construction commodities, including steel, concrete, wire, cable and copper. The effects of rising commodities prices and higher interest rates can be expected to lead to price hikes for all SMRs — not just NuScale’s design.

Second, the new $89/MWh target price of power already means that power from the NuScale SMR will be much more expensive than that from renewable and storage resources even with an estimated $4.2 billion in taxpayer subsidies. The U.S. Department of Energy has provided $1.4 billion of funding to the SMR project, and the recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act offers an additional subsidy estimated at $30/MWh. Without the billions in taxpayer backing, the price of the power from the NuScale SMR would be substantially higher than $120/MWh.

Finally, NuScale doesn’t expect to start nuclear construction until 2026. Assuming it’s completed on time — an optimistic outlook, given the nuclear industry’s long history of construction delays — the reactor won’t be fully operational before the end of 2030. This timeline gives construction costs another eight years to go up, potentially pushing the power price even higher into the stratosphere.

The nuclear industry has been criticized for overpromising and underperforming because it has repeatedly understated the high costs of building new reactors. A 1986 federal analysis of nuclear power plant construction found that the actual costs of building 75 new reactors between 1960 and 1980 was triple the projected costs, and the plants took twice as long to build as projected.

Skeptics don’t have to go back to 1986, though. The two reactors under construction at the Vogtle Project in Georgia were originally projected to cost $14.1 billion and be completed in 2016 and 2017. The two have so far cost $34 billion. Neither unit has gone online yet, though Georgia Power currently expects Unit 3 to start operating this year and Unit 4 to start operating late this year or early next year.

SMRs are being marketed as a solution to the climate crisis, but they're already far more expensive and take much longer to build than renewable and storage resources — technologies we already have. The gap is only going to get larger as the costs of building SMRs rise and costs of renewables and storage continue to decline. And locking in capital investments for SMRs could very well divert limited resources and prevent more effective investments in renewables and storage.

Using SMRs as backups for renewables will not be financially feasible. Almost all of the costs of producing electricity with nuclear power are fixed, meaning they have to be paid, no matter how much or how little power the SMR produces. Cycling SMRs to load-follow renewables will push their average power prices even higher by pushing down their total generation.

SMRs also can be expected to take much longer to build than proponents claim. Instead of waiting a decade or longer for SMRs, we should add all of the wind, solar, geothermal and storage capacity that we can, as quickly as we can. Greenhouse gas emission reductions achieved in the near term have a bigger impact than ones that might be obtained a decade or more in the future.

An old adage is that anything that sounds too good to be true probably is. Given the history of the nuclear power industry, everyone — utilities, ratepayers, legislators, federal officials and the general public — should be very skeptical about the industry’s current claim the new SMRs will cost less and be built faster than previous designs.