The meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear power plant in 2011 essentially put the nail in the coffin of the construction of big nuclear power plants with similar technologies in the U.S., according to nuclear proponents and watchdogs. That disaster, along with earlier accidents, ongoing delays and cost overruns at the Vogtle nuclear plant in Georgia, has added to the tailwinds of taking the nuclear technology known as small modular reactors, or SMRs, to market. The drive to decarbonize, along with the war in Ukraine and Europe’s loss of Russian natural gas supplies, has further bolstered interest in the baseload capacity that could come from SMRs.

The leading U.S. developer of SMR technology went public last month, the first company of this kind to do so. The revamped NuScale Power entered the stock market May 3 after merging with a special purpose acquisition company Spring Valley Acquisition. NuScale is the farthest along in the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s approval process of any company developing SMR technology.

John Hopkins, NuScale president and chief executive officer, said during an announcement of going public that being the first publicly-traded company to design and deploy SMR technology was “a historic moment” for the company, enabling it to accelerate its “efforts to help meet the world’s urgent clean energy needs.” Fluor Corporation is the company’s majority investor.

But reactions to NuScale being traded on the New York Stock Exchange have been mixed. Some analysts have heralded the prospects of the company’s small reactors helping to meet clean energy goals with carbon-free nuclear power in the U.S. and abroad. Others insist that NuScale’s reactors are just a smaller version of the current dangerous and costly nuclear power plants, which create long-lived radioactive waste.

Ahead of competitors

The company is ahead of its competitors in the SMR space because it is using existing light water reactor technology but it is also “fighting against economies of scale,” said Edwin Lyman, the Union of Concerned Scientists’ director of nuclear power safety. While this kind of SMR at 77 MW is less expensive than a large light water reactor, the electricity from the SMR is more expensive because its projected costs are steep and far less power would be sold, he added. That is causing NuScale to look to “cut costs to the bone,” compromising safety, he said.

“There is an amazing dichotomy of people on each side of the issue” of whether NuScale going public is a significant step towards commercialization of its technology, said Richard Rys, senior consultant with technology consulting firm ARC Advisory Group.

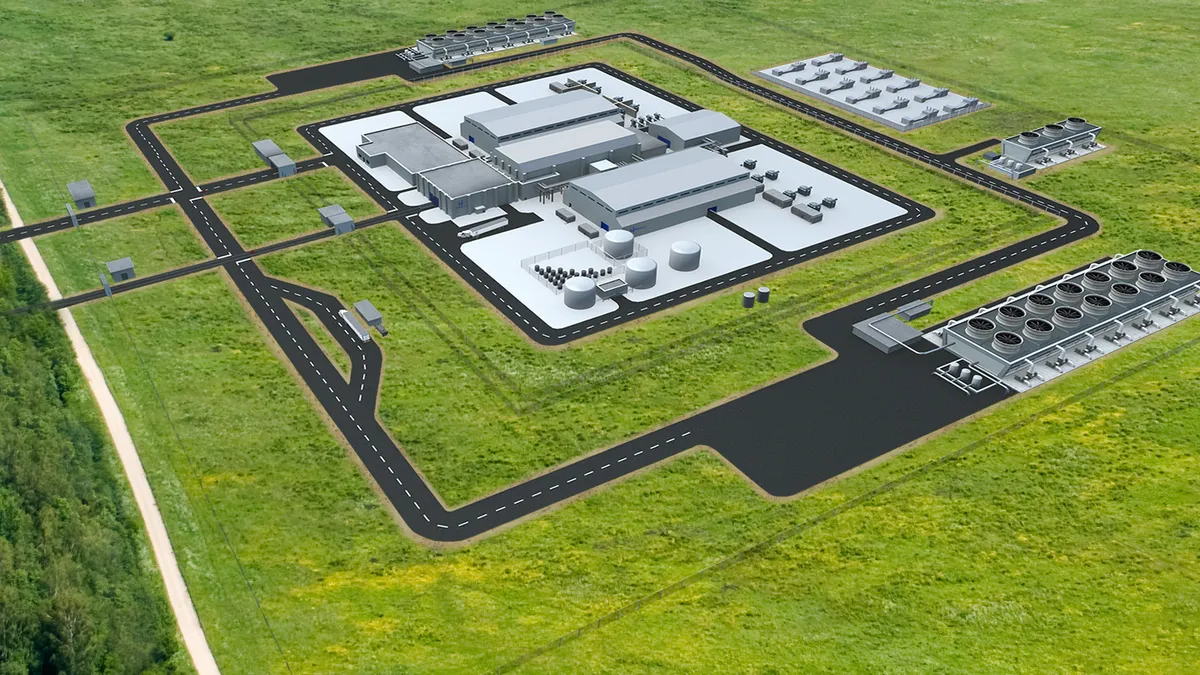

NuScale’s SMR and ones being developed by other companies entail a technology allowing modular construction, with the small reactor units being installed side by side. That is projected to allow faster and less costly construction, according to the Department of Energy. SMRs are mini reactors with up to 300 MW of capacity, according to the World Nuclear Association.

“Economies of scale are envisaged due to the numbers produced,” the World Nuclear Association said of SMR technologies last month. DOE said in late 2018 that it would back NuScale’s project over several years with $1.4 billion. But its proposed Fiscal Year 2023 budget would provide NuScale only $40 million, according to the agency.

The company’s first SMR is not expected to come online before 2029 and it requires significant financing to stay afloat until then, proponents and critics say.

“They need a lot of financing as their first reactor won’t start running until 2029,” said Rys, a nuclear engineer who has worked on many large projects. A public offering, he added, “is a measure of the confidence in the company, which is essential for their future.”

NuScale’s stock price has fluctuated between $8.56 and $11.23 since it went public. Just before its public offering, NuScale was valued at around $2 billion. Its market capitalization at the end of May was $2.16 billion.

“As a result of the business combination [with Spring Valley], NuScale received gross proceeds of approximately $380 million,” Diane Hughes, the company’s vice president of communications, said.

To be a viable company that sells pricey products, a solid balance sheet is necessary, Debra Fiakas, managing director of Crystal Equity Research, which analyzes small-capitalization companies, said about companies that go public. She added that raising capital via a special purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, was one way to finance the company.

But entering the market as a SPAC which uses what is essentially a shell company, however, comes with more risks than using an existing company to launch a traditional initial public offering. Business combinations to allow market entry as a SPAC “have suffered sharper losses than the benchmark equity index,” analyst Joshua Enomoto wrote in a May 2 assessment of NuScale for financial media outlet Benzinga.

Broken promises?

Portland-based NuScale says it will create an “energy source that is smarter, cleaner, safer, and cost competitive.”

Those “promises have been made and broken repeatedly throughout the history of the nuclear power industry,” countered a February report by Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

But IEEFA Director of Resource Planning Analysis and report co-author David Schlissel welcomed the company’s entry into the public market. “I think it is a good move as now they will be held to a stricter standard as to what they claim,” including the company's projected $58/MWh price tag for its key project with Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems, or UAMPS, he said.

NuScale reached an agreement generally in 2017 with 33 of the 50 members of UAMPS to provide a dozen 50 MW modules to be sited at the Idaho National Laboratory and come online in 2024, according to DOE. The initial 600 MW project was subsequently revised to six larger modules of 77 MW each due to come online in 2029. The current number of participants is 27, UAMPS spokesperson LaVarr Webb said. Several members dropped out in 2020.

But the project changes, according to Webb, were made early on, and having 27 members involved is on the high side for members electing to sign on to a UAMPS power project, he said, adding that UAMPS was pleased to see NuScale go public.

Webb said the estimated cost of NuScale’s 462 MW project is $5.3 billion. "That includes financing over 40 years and takes into account inflation, escalating wage rates" and other variables, he noted

IEEFA’s Schlissel takes issue with what he calls NuScale’s $58/MWh low-ball estimate but said even if it were a bona fide number, it is much higher than the cost of renewable projects. Utility-scale solar-plus-storage costs are about $45/MWh and falling; wind power costs are $30/MWh and dropping, and utility-scale solar alone costs are at $32/MWh and falling, he noted.

“SMRs will cost at least $35 million per year more than the alternative” emissions-free portfolios, a 2019 report for Healthy Environment Alliance of Utah by consultant Energy Strategies concluded. “On a present value basis, the alternative portfolios offer between $298-$355 million in savings compared to the SMR Base Case portfolio,” Energy Strategies concluded. A critical issue related to successful commercialization is that the design of NuScale’s UAMPS project has not yet been fully certified by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

In August 2020, NuScale was the first small modular reactor developer to pass the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s safety evaluation and at that time a license was expected to be completed by August 2021.

But the UAMPS reactor design was expanded from 50 MW to 77 MW and NRC staff have raised concerns about the company’s seismic analysis. In addition, unresolved safety issues might lead to greater costs during the operating license phase, Union of Concerned Scientists’ Lyman warned.

“The biggest issue is cost and the second is risk,” Rys agreed.

NuScale plans to submit its Standard Design Approval to the NRC this year and hopes it will be approved in 2025, Hughes said.

As NuScale prepares its submission, it will take about a year after the initial public offering to know if NuScale is solid financially, according to Rys.

But the company could have first-mover advantage.

The first SMR developer “to get out there will dominate the business and put the others out of business,” Rys predicted.