Dive Brief:

- The Nuclear Regulatory Commission is updating its power plant licensing regulations to adapt to technological changes brought on by the development of advanced nuclear reactors and small modular reactors, or SMRs.

- The NRC proposes to establish a “technology-inclusive regulatory framework” for applicants for new commercial advanced nuclear reactors. The regulations released Monday and currently in draft form and proposed by NRC staff, would evaluate nuclear plant proposals based on risk and performance “that are flexible and practicable for application to a variety of advanced reactor technologies.”

- Backers say the proposal is needed to promote zero-emissions power, but critics say it’s excessively lengthy and overly complicated.

Dive Insight:

Updating licensing regulations is tied to the drive to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, even as critics say developers and advocates overpromise on the time and money needed to build nuclear plants.

President Donald Trump signed the Nuclear Energy Innovation and Modernization Act into law in 2019. Sen. John Barrasso, R-Wyo., then chairman of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, said at the time the law is “critical if we are going to reduce carbon emissions in a meaningful way.”

The legislation was enacted with overwhelming bipartisan support, passing the Senate on a voice vote and clearing the House, 361-10. It directs “regulatory processes necessary to allow innovation and the commercialization of advanced nuclear reactors.” Among other requirements, the law calls for performance metrics and milestone schedules and directs the NRC to update the process for research and test reactor licensing. Regulations would take effect Dec. 31, 2027.

Current application and licensing requirements in some cases include requirements specific to large light-water and other reactors, the NRC said. NRC staff expect additional updates to nuclear plant licensing regulations beyond the ones already proposed.

The regulations now in effect have been developed over the course of decades and reflect changes to address events learned from nuclear plant operations, the NRC said. In contrast, the new regulations are being developed to “accommodate technologies that, in some cases, lack significant operating experience.”

That’s a key problem, said Edwin Lyman, director of nuclear power safety at the Union of Concerned Scientists. In a recent interview, he asked how regulators can license new technologies if they “don’t know how they work.”

Adam Stein, director for nuclear energy innovation at Breakthrough Institute, an energy research group, wrote on its website that current reactor regulations “just don’t fit tomorrow’s designs.”

“So the NRC has to develop an entirely new way to license new kinds of reactors,” he said.

More than 1,200 pages of the draft proposed rules include discussion on reactor design and accident vulnerability, staffing of advanced reactors and SMRs; an analysis of knowledge, skills and abilities related to qualifications for nuclear plant workers; construction and manufacturing; and a range of other activities related to operating a nuclear power plant.

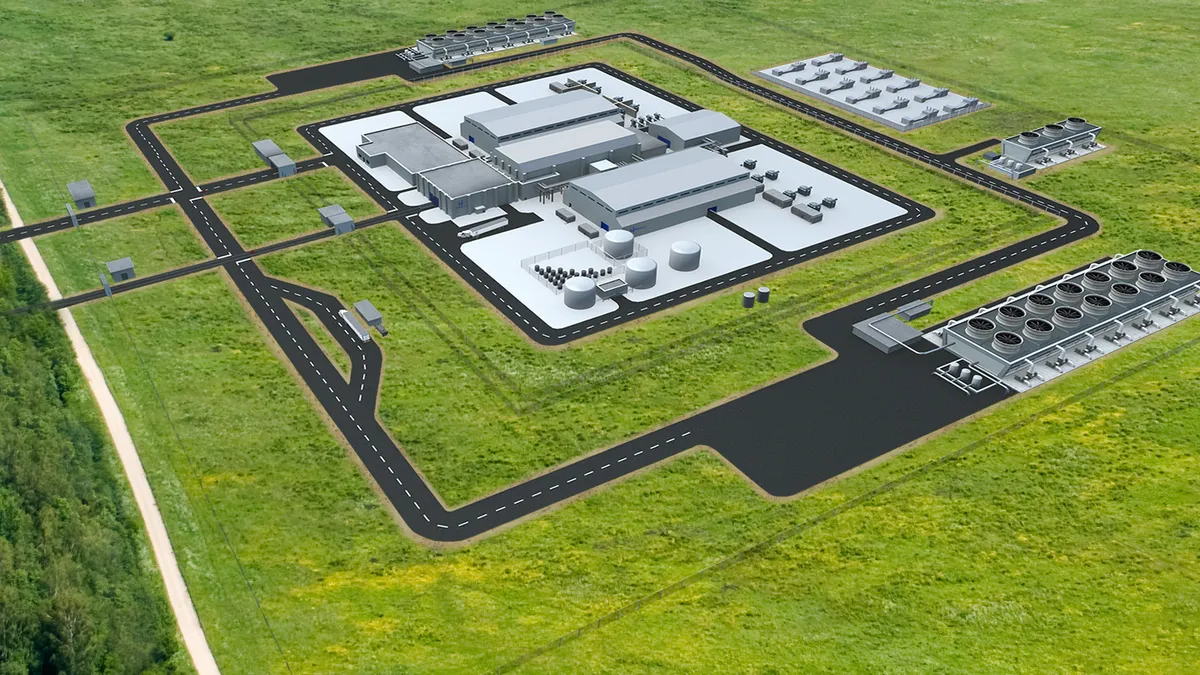

For example, unlike large light-water reactors, SMRs are factory-built, with modules assembled on-site. NRC rules must reflect the change, said Judi Greenwald, executive director of the Nuclear Innovation Alliance, a think tank. She compared the new technology to the auto industry as it transitions to electric vehicles from internal combustion engines.

Lyman told the NRC its staff is broadly interpreting federal legislation “as giving it carte blanche to rewrite the entire framework for licensing and oversight of all nuclear power reactors.”

In comments to the NRC Aug. 31, he said the Union of Concerned Scientists is “deeply disappointed” the agency has failed to use the new rule-making process to require that new reactors demonstrate a higher level of safety than the operating fleet licensed under the current rules.

The Breakthrough Institute criticized the length of the draft proposed regulations.

“NRC staff claim they have met the mandate given to them by Congress,” Ted Nordhaus, founder and executive director, and Stein wrote on the organization’s website. “But the sheer length of the proposed regulations alone demonstrates this is not the case.”

The draft framework is twice as long as either of previous licensing frameworks it’s intended to replace, they said. The NRC staff added more regulations, including health objectives and expanded requirements for a radiation standard, “a further invitation to endlessly ratchet regulatory requirements,” they wrote.

Nordhaus and Stein suggest a “clear and reasonable standard for acceptable radiation exposure to plant workers and the public” that allows license applicants to demonstrate that the proposed reactor design can achieve that standard.

The Nuclear Energy Institute, an industry trade group, said in August the critical concerns are that the proposed requirements “increase complexity and regulatory burden without any increase in safety and reduce predictability and flexibility through the inclusion of prescriptive details that are typically found in guidance.”

Lyman said the proposed regulation’s “broad scope and formidable complexity” could make it more difficult to clearly assess whether the rule meets the agency’s goal of providing at least the same degree of protection of public health and safety as for current-generation light-water reactors.

The Nuclear Innovation Alliance suggested that most of the draft proposed rule requirements can be kept, “but moved to regulatory guidance or non-mandatory appendices of the rule text to provide optional pathways” for applicants who are interested in using a “more prescriptive, predictable process.”