The following is a guest post from Brett Feldman, principal research analyst at Navigant Research. To submit a viewpoint article, please review these guidelines.

On May 17, 2017, Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) made an announcement that flew under the radar of most of the energy industry.

The latest trend among utilities and grid operators appears to be forgoing traditional transmission and distribution (T&D) upgrades for alternative methods to meet system needs, and BPA chose to take “a new approach to managing congestion on our transmission grid,” according to CEO Elliot Mainzer, rather than build a new $1 billion, 80-mile transmission line along highway I-5 in Oregon.

This decision “reflects a shift for BPA—from the traditional approach of primarily relying on new construction to meet changing transmission needs, to embracing a more flexible, scalable and economically and operationally efficient approach to managing our transmission system.” The preferred solution includes resources like battery storage, flow control devices, and demand response. Such projects have become known as non-wires alternatives (NWA), and are proliferating across the country.

The definition of NWA varies around the United States and the world. Navigant Research defines NWA as:

“An electricity grid investment or project that uses non-traditional T&D solutions, such as distributed generation, energy storage, energy efficiency demand response, and grid software and controls, to defer or replace the need for specific equipment upgrades, such as T&D lines or transformers, by reducing load at a substation or circuit level.”

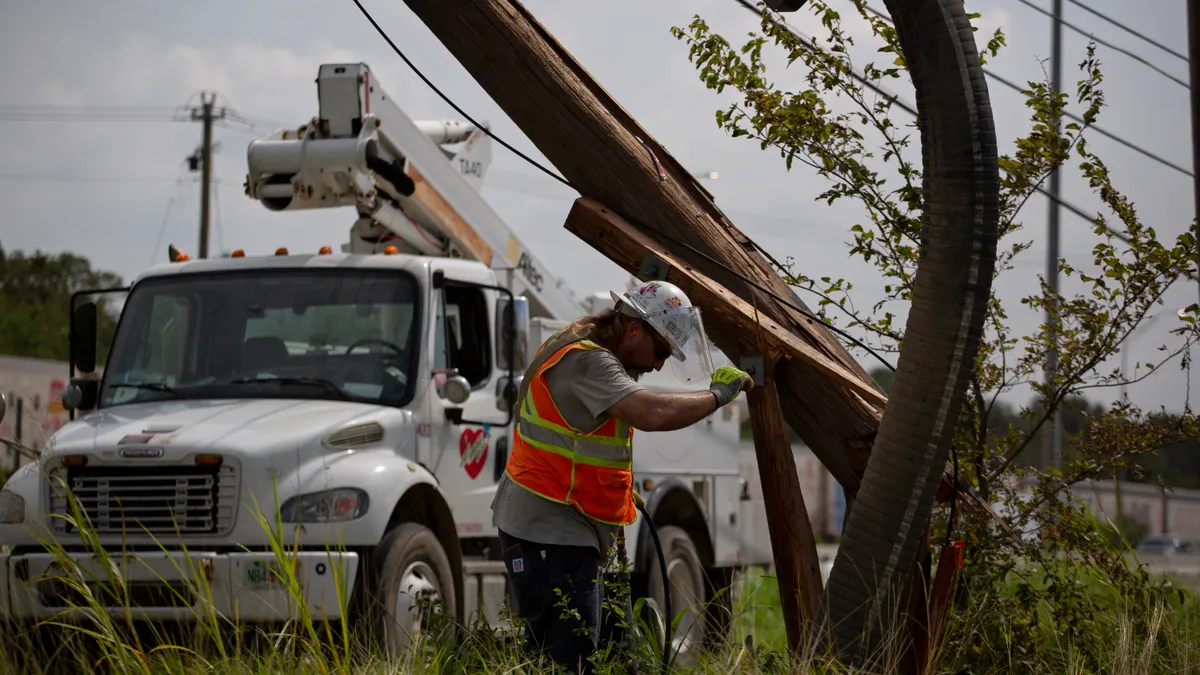

Traditionally, when a transmission or distribution system operator had a need to upgrade or replace infrastructure due to aging equipment or increased load demand, it would simply conduct poles and wires projects on which it could earn a regulated rate of return. No thought was given to alternatives in addressing the issue; it was simply seen as replacing a part in the electric grid machine.

However, more creative solutions are being explored to address infrastructure needs at a lower cost with higher customer and environmental benefits as grid management and distributed energy resource (DER) technology has improved. Utilities now look to increase customer engagement and provide more value-added services, and policy concerns related to cost and the environment have grown.

At this early stage in development, there is no standard business model and procurement process for utilities to implement NWA. Currently, there are four models being considered and tried by utilities. The first is request for proposal (RFP), a typical utility procurement model. Auctions are another, borrowed from wholesale market models to drive the lowest-cost solutions. Also being considered is procurement with current implementation contractors to keep things simple and quick. The last possibility is internal utility resource deployment if the utility has the required capabilities.

There is no one right answer for all situations; each case will depend on the utility’s internal structure and capabilities along with the regulatory construct in which it operates.

NWAs around America

Several utilities in different state jurisdictions have undertaken NWAs with diverse program design and procurement models. In California, Southern California Edison and Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) have each implemented multiple NWA projects to address load growth pockets, retirement of nuclear generation, and natural gas storage leaks.

PG&E has developed a targeted, least-cost planning demand-side management (DSM) framework to support distribution system reliability. Using DSM to defer investments in T&D capacity frees constrained capital to fund other, more valuable projects for the utility. Furthermore, PG&E believes that customer engagement with a DSM program significantly increases customer satisfaction.

In New York, all investor-owned utilities are required to consider NWA as part of the state's Reforming the Energy Vision. Con Edison has implemented the largest NWA to date; the Brooklyn-Queens Demand Management program, a $200 million investment to defer a $1 billion substation upgrade.

The program relies largely on energy efficiency measures, from traditional incentives for replacing inefficient appliances and air conditioning units to new building management systems. However, the program also calls for other DER such as fuel cells, demand response, and energy storage, and it employed a novel descending clock auction process to procure the resources for this program, as opposed to simply issuing an RFP.

Central Hudson Gas and Electric also began an NWA in New York, although on a much smaller scale. It incorporates an innovative model to share the investment savings between the utility and its customers whereby 70% of benefits would go to ratepayers through natural rate moderation, and 30% of benefits would be provided to the utility as an incentive to run the program effectively.

National Grid executed an NWA in Rhode Island to meet load growth needs in parts of its territory in response to a State of Rhode Island law requiring distribution utilities to develop cost-effective energy efficiency before constructing expensive new supply. Basically an enhanced version of its existing energy efficiency programs, it added demand response on top of them. The utility has found that different marketing methods are required for such a localized effort to succeed, versus its typical system-wide programs.

NWA is likely to become more common in U.S. utility capital planning processes and regulatory requirements in many state jurisdictions. It is an exciting yet anxiety inducing opportunity to change the way utilities address system and customer needs simultaneously. The sooner the industry faces this new reality, the better prepared all parties can be to ensure it succeeds. For more on this subject, Navigant Research’s report, Non-Wires Alternatives, discusses the drivers, barriers, business models, and future growth of the market.