New utility cybersecurity strategies are needed to counter sophisticated intrusions now threatening the operations of an increasingly distributed power system’s widening attack surface, security analysts agree.

There are cyber vulnerabilities in “every piece of hardware and software” being added to the power system, the September 2022 Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, or CISA, Strategic Plan 2023-25 for U.S. cybersecurity reported. Yet 2022 saw U.S. utilities propose $29.22 billion for hardware and software-dependent modernizations, the North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center reported Feb. 1.

New hardware and software can allow malicious actors to have insider access through utilities’ firewalled internet technology to vital operations technology, cyber analysts said.

“No amount of traditional security will block the insider threat to critical infrastructure,” said Erfan Ibrahim, CEO and founder of independent cybersecurity consultant The Bit Bazaar. “The mindset of trusted versus untrusted users must be replaced with a new zero trust paradigm with multiple levels of authentication and monitoring,” he added.

Growing “distribution system entry points” make “keeping hackers away from operations infrastructure almost unworkable,” agreed CEO Duncan Greatwood of cybersecurity provider Xage. But distributed resources can provide “resilience” if a distributed cybersecurity architecture “mirrors” the structure of the distribution system where they are growing to “contain and isolate intrusions before they spread to operations,” he said.

New multi-level cybersecurity designs can provide both rapid automated distributed protections for distributed resources and layers of protections for core assets, cybersecurity providers said. But the new strategies remain at the concept stage and many utilities remain unwilling to take on the costs and complexities of cybersecurity modernization, analysts said.

The threat

Critical infrastructure is already vulnerable to insider attacks.

The 2021 Colonial Pipeline shutdown started with a leaked password, according to public reports. A 2019-2020 attack known as SUNBURST and directed against U.S. online corporate and government networks went through SolarWinds and other software vendors, CISA acknowledged. And Russia’s 2015 shutdown of Ukraine’s power system was through authenticated credentials, likely using emails, CISA also reported.

In 2021, there were ransomware attacks on 14 of the 16 U.S. “critical infrastructure” sectors, including the energy sector, the FBI reported. And new vulnerabilities allowed attacks that also caused data losses, disrupted network traffic, and even denial-of-service shutdowns, according to technological and research firm Gartner.

Attacks on utility OT can come through distributed solar, wind and storage installations, employee internet accounts, smart home devices, or electric vehicles, Gartner, other analysts, and the May 2021 Biden executive order requiring improved power system cybersecurity agreed.

Existing Critical Infrastructure Protection, or CIP, Reliability Standards established by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation, or NERC, are inadequate, a January 2022 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission said. They focus only on defending the “security perimeter of networks,” the commission said.

“Vendors or individuals with authorized access that are considered trustworthy might still introduce a cybersecurity risk,” the rulemaking said. The RM22-3-000 proceeding will provide direction on how to update CIP standards to better protect utilities, federal regulators added.

The most recent Biden administration and FERC initiatives focused on the power sector, though utilities and system operators declined to reveal information about vulnerabilities or actual attacks.

There were an “all-time high” 20,175 new OT vulnerabilities in U.S. networks identified by cybersecurity analysts in 2021, according to a 2022 assessment by cybersecurity provider Skybox Security. And faster and more frequent exploitation of new vulnerabilities in 2021 showed “cyber-criminals are now moving to capitalize on new weaknesses,” it added.

A December 2021 CISA Emergency Directive recognized exploitation of a vulnerability in the Apache Log4j tool that records and scans almost all communications between online systems, the Wall Street Journal reported at the time. Downloaded millions of times, it could allow attackers to send and execute malicious code and is unlikely to be “fully ‘fixed’ for years,” cybersecurity specialist Wei Chieh Lim blogged in May 2022.

The Log4j vulnerability “was so trivial it was first exploited by Minecraft gamers,” showing utilities could be unaware of “hundreds, if not thousands, of vulnerabilities,” said CEO Tony Turner of cybersecurity provider Opswright.

A software bill of materials, or SBOM — an inventory of all system components — could be a solution to vulnerabilities like Log4j, cyber analysts said.

SBOMs were mandated by the May 2021 Biden executive order. And SBOM best practices and minimum requirements were added in a July 2021 National Telecommunications and Information Administration report. But SBOMs “are only one element” in the needed cybersecurity rethinking, consultant and provider Ibrahim said.

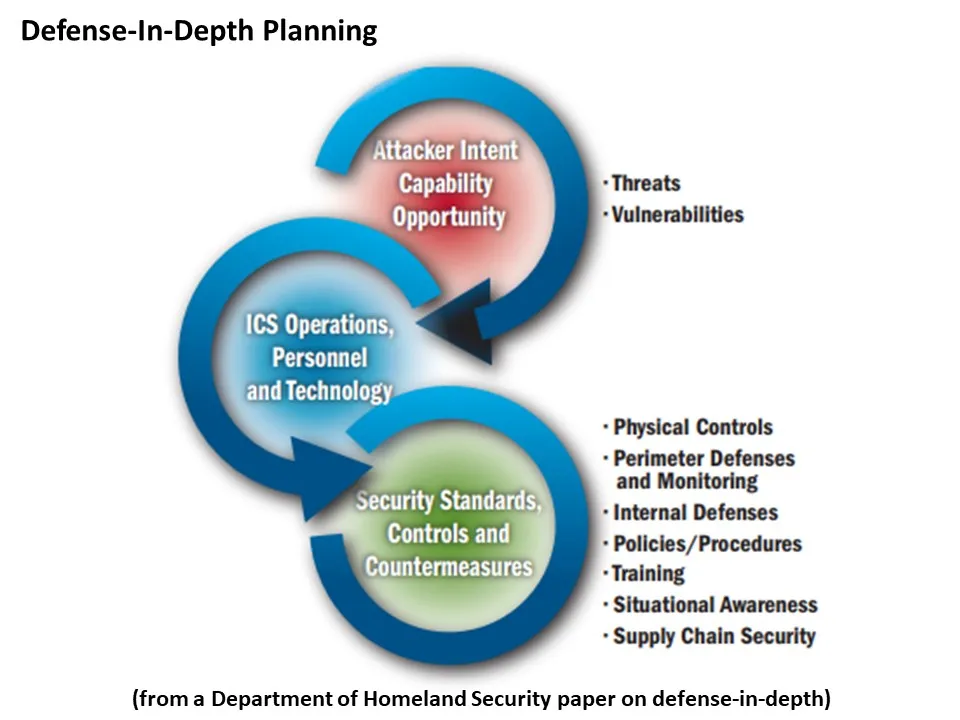

Internet technology began with firewalls and outward-facing defenses, but new distributed power systems make penetrations into the outer layers of networks almost inevitable, Ibrahim and other cybersecurity analysts said. Only a multi-faceted cybersecurity architecture throughout a utility’s operations can protect both OT’s new distributed attack surface and its vital operational core, many agreed.

Conceptual solutions

The most common utility cybersecurity approach is compliance with NERC CIP standards, and possibly with narrower International Society of Automation, or ISA, 62443 standards, Opswright’s Turner said. But the NERC CIP standards are being reformed and ISA standards “are narrowly focused on vulnerabilities in automation and control systems,” Turner said.

A new Department of Energy “cyber-informed engineering,” initiative may offer better cybersecurity for critical infrastructure, Turner said. It proposes to “engineer out” risk “from the earliest possible phase of design” of the OT system’s cyber-defense, which is “the most optimal time to introduce both low cost and effective cybersecurity,” DOE’s paper said.

Utilities need to “close the gap” between IT and OT systems, said Skybox’s Senior Technical Director David Anteliz. But the “complexity of multi-vendor technologies” and “disjointed architectures across IT and OT” increase security risk, as do increased accesses by third parties for which “less than half” of utilities have policies, a Skybox November 2021 survey found.

“I can guarantee you there are people doing things in the background at utilities now,” Anteliz said. “Skybox’s answer is automation of defense-in-depth and layered architecture, which provides ongoing monitoring, visibility, understanding and response to what needs to be secured and where,” he added.

Segmentation in the design can isolate utility control rooms and make them “vaults,” Skybox’s 2022 vulnerability trends paper said. And automated aggregation of data and system information from “every corner of the network” can inform automated reactions and provide “ongoing oversight” that allows utilities to move “from reaction to prevention,” it added.

Other cybersecurity analysts have designed detailed zero trust and defense-in-depth conceptual architectures that can be applied to the U.S. power sector.

The first of “four functional levels of security” is basic “network hygiene,” by establishing user access rules and priority lists, use cases, and necessary transactions, the Bit Bazaar’s Ibrahim said. Properly applied interactions can be limited “to those who need to transact,” he said.

The second level is a “signature-based intrusion detection system,” or IDS, which automates the established priority lists to limit accesses to “authenticated users and a valid use case,” he said. The third level is a “context-based” IDS, which expands on the access limitations by “blocking or flagging” inadequately authenticated transactions, Ibrahim said.

Those IDS function “in stealth mode,” unseen even by insiders, but every network session is monitored, and any “departure from normal transactions and rules” terminates the session, he said. Utility security incident and event management systems detect and analyze all transactions, and respond to and report those questioned or terminated, Ibrahim said.

The fourth level, “endpoint security,” is overseen by automated “hypervisor” software and has three layers of protection, Ibrahim said. An intrusion may “corrupt” target applications, but the “endpoint hardware” will be protected by the hypervisor and a “last gasp message” may allow a network edge mesh or network core defenses to avoid a “cascading” OT network failure, he added.

Mesh “is a collaborative ecosystem of tools and controls” to protect a power system’s expanding perimeter of distributed resources and vulnerable third-party devices, according to Gartner. Its “distributed security tools” offer “enhanced capabilities for detection” and “more efficient responses” to intrusions, Gartner added.

Mesh cannot eliminate insiders with “legitimate credentials,” which is why utility hardware- and software-dependent system modernizations “should have multi-layer defenses and every line of new code checked,” Ibrahim said. But “if a system is compromised at its edge, like at the level of smart meters or EV chargers, mesh can respond to avoid the compromise spreading,” he said.

These conceptual architectures “can increase situational awareness and control,” but most utilities are still focused on complying with NERC CIP standards to avoid fines, Opswright’s Turner said. Many utilities argue that designed cyber-defense “complexities can slow and confuse system monitoring and responses,” and that the increased security does not justify the cost, he added.

It is, however, “not clear there is a better choice,” because firewalling the coming power system’s potentially millions of distributed devices “is not practical,” he said.

A hierarchical zero trust architecture with a firewalled core, a monitored middle layer of gateways protecting operations and a mesh at the network’s edge is the emerging consensus solution to comprehensive OT system security, Turner, Ibrahim and others agreed.

But attacks are proliferating despite federal directives and mandates and proposed provider concepts, showing more work is needed, cyber-experts and power system stakeholders agreed.

A utility-sponsored cybersecurity sandbox

Work continues in the public and private sectors to develop zero-trust tools and technologies that will enable the conceptual architectures to better defend OT for the electric power and other sectors.

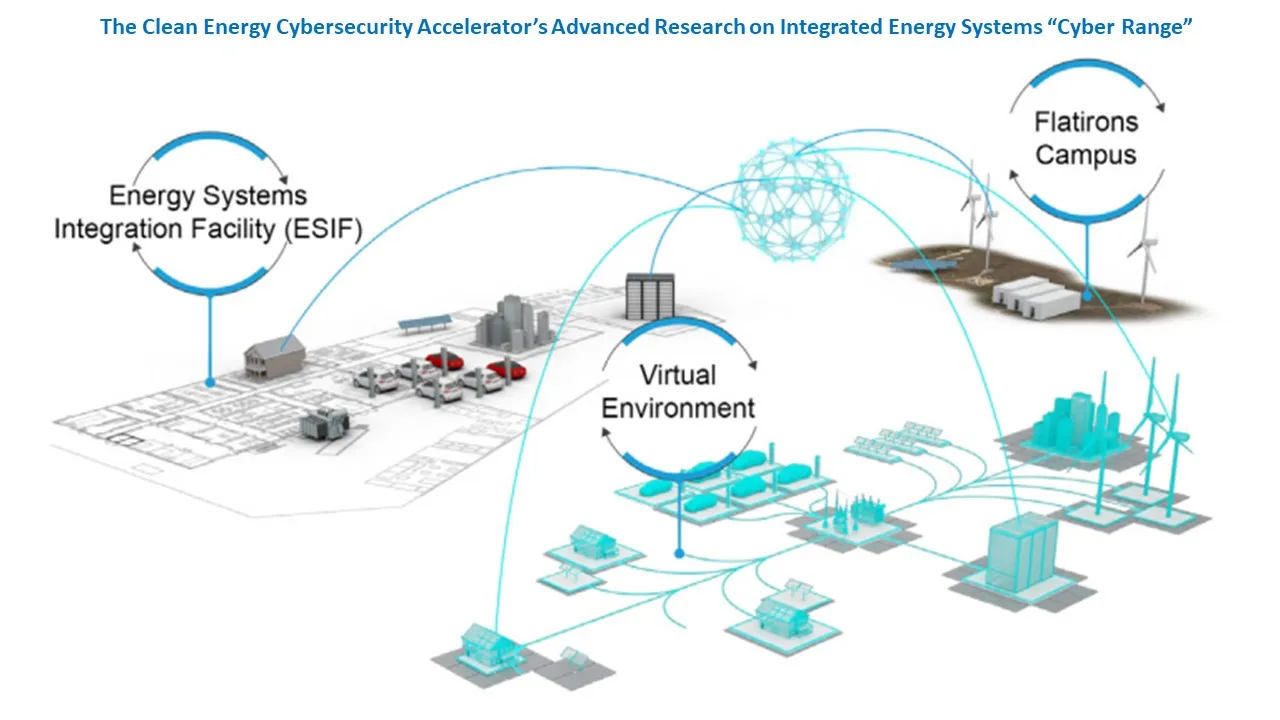

The Clean Energy Cybersecurity Accelerator, or CECA, program from DOE’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory, launched in December, is a “sandbox” for innovative cybersecurity pilot projects. It will deploy and test strategies for addressing new power system vulnerabilities introduced by clean energy technologies, the CECA website said.

“U.S. critical infrastructure is increasingly targeted by adversaries,” NREL Director, Cybersecurity Research Program, Jonathan White told a January 17 CECA planning webinar. Funded by the program’s utility sponsors, which include Duke Energy, Xcel Energy and Berkshire Hathaway, or BHE, solutions will be assessed using NREL’s Advanced Research on Integrated Energy Systems, “Cyber Range,” NREL scientists told the webinar.

The Cyber Range is NREL’s proprietary, up-to-20 MW renewables-powered system integrated with distributed resources like electric vehicles and batteries and built for testing innovative technologies, according to NREL. First CECA demonstrations will test Xage, Blue Ridge Networks and Sierra Nevada Corp. cyber defense approaches.

BHE wants to leverage NREL’s “rigorous testing,” to find “technical solutions” and effective “fast-track technologies” to improve cyber defenses, BHE Spokesperson Jessi Strawn said.

CECA will allow utilities and solution providers to “stress-test disruptive security technologies,” and give “defenders” an opportunity to “get ahead of threat actors,” added a statement from BHE Director of Security and Resilience Jeffrey Baumgartner.

Duke Energy is “regularly approached by vendors who have innovative technologies” and CECA is a way to “test them in a non-live environment,” said Duke spokesperson Caroline Portillo. The opportunity is especially valuable because the tests will be “at scale in a sandbox environment,” and will be followed by technical performance assessments by participating sponsor utilities, she added.

Results of initial tests for authenticating and authorizing distributed energy resources integrated into OT environments “will be critical” as Duke and other utilities add those resources, Portillo said.

“The point of the NREL program is to build a neutral ground for solution providers and utilities to collaborate on OT cybersecurity innovations,” said Xage CEO Greatwood. “Tech companies have been frustrated by the stately pace of change in the utility business,” he added.

But if “end user utilities engage” in CECA, “tech companies will gain [an] understanding of their needs” and utilities can “obtain technical validation” of solutions, he added. “Xage already has utility customers,” but this is a chance for it to demonstrate how an automated, widely-present mesh defense like Xage Fabric works “in a zero trust cybersecurity architecture for OT environments,” Greatwood said.

A system “is only as secure as its weakest link” and “the weakest link in power systems with millions of distributed resources is not very secure because it offers a lot of entry points for attackers,” he said. “Mesh architecture mirrors the distributed physical architecture” and “can recognize and isolate, or at least control,” intruders without proper authorization and authentication, Greatwood added.

The power system environment “is evolving” toward “growing network, infrastructure and architectural complexity,” and “vulnerabilities will persist,” Gartner observed in January 2022.

But those vulnerabilities must be addressed because limiting “access to critical systems can be the greatest impediment to cyber breaches,” Ibrahim said. Building the best protections “may take time, money and a change in management processes, but those are small costs compared to the billions that can be lost from a successful intrusion,” he added.