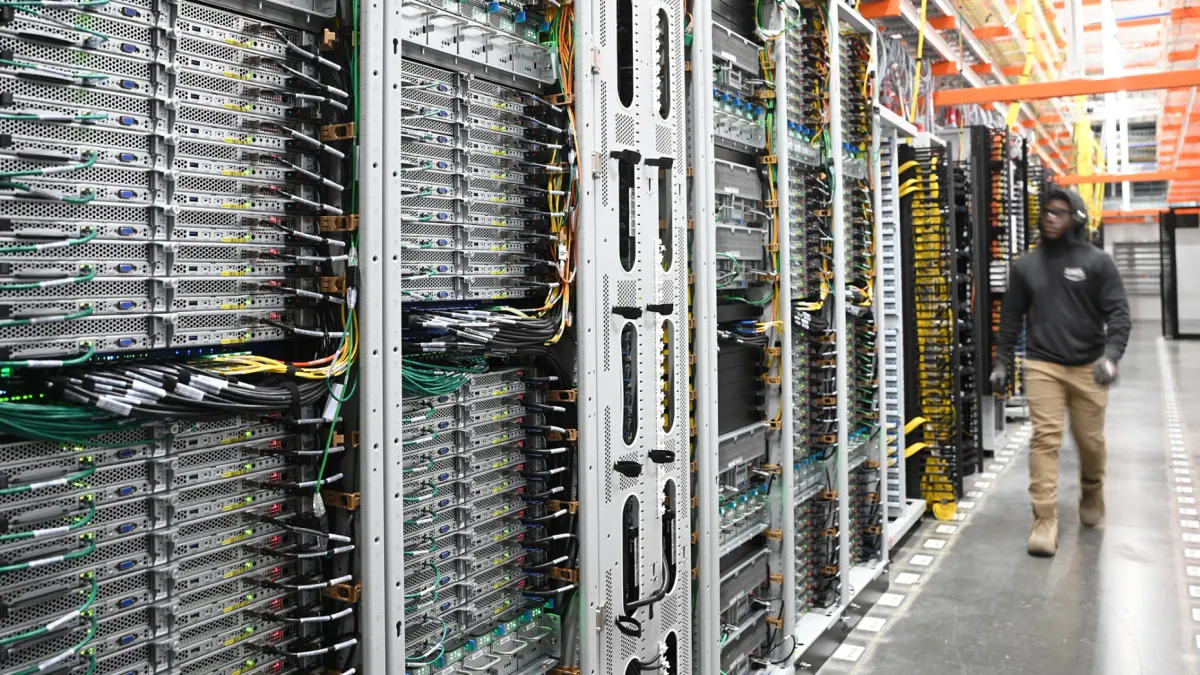

The U.S. energy storage industry finds itself at a crossroads in the aftermath of the January blaze at the 300-MW first phase of Vistra’s Moss Landing energy storage facility near Santa Cruz, California.

Nearby residents reported feeling ill in the days after the blaze, and a legal team that includes celebrity environmental activist Erin Brockovich cited possible soil contamination in a lawsuit filed earlier this month. One local elected official compared the incident to the 1979 accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant. Another sponsored a bill to increase zoning setbacks for new energy storage facilities. Elsewhere in California, elected officials in San Luis Obispo and Orange counties enacted moratoriums on utility-scale energy storage development.

Energy storage experts note that the Moss Landing facility was housed indoors and used a type of battery more prone to thermal runaway, among other potential safety issues. Utility-scale lithium-ion battery installations’ overall safety track record is impressive, with just 20 fire-related incidents over the past decade despite a 25,000% increase in installed capacity since 2018, a spokesperson for the American Clean Power Association told Utility Dive last month.

But the Moss Landing incident has nevertheless focused utilities, regulators and lawmakers attention on lithium-ion battery safety. It could also create an opening for non-lithium energy storage technologies to compete, some experts say.

Backlash fears spur renewed focus on lithium-ion battery safety

Despite the political backlash, the Moss Landing incident is unlikely to dent demand for battery systems in the long run, according to experts interviewed by Utility Dive.

“We don’t think Moss Landing will have a very material impact,” said Tim Woodward, managing director at Prelude Ventures. Woodward’s firm is an investor in Element Energy, which offers a proprietary battery management system it says significantly improves battery safety, efficiency and longevity.

The industry has made great strides on battery safety since Vistra commissioned Moss Landing One in 2020, said Ravi Manghani, senior director of strategic sourcing at Anza, a solar and storage analytics firm. He cited the advent of national energy storage safety standards like UL 9540, UL 9540A and NFP 855, all of which factor into a model energy storage ordinance framework released in June by the American Clean Power Association.

“We expect the industry to use this incident as a learning opportunity and push the envelope on safe operations of the multiple gigawatt-hours of projects that are projected to go online in the coming years,” Manghani said.

Such envelope-pushing could benefit technology providers like Element, which claims to “eliminate fire risk” while reducing total cost of ownership by 20% in first-life battery storage systems and 40% in second-life systems. Whereas legacy BMS technology treats the entire battery as a static system, Element’s BMS enables real-time monitoring, diagnostics and controls at the cell level, it says.

“Fundamentally, we think this technology could predict the elements that may result in thermal runaway 50 to 80 cycles in advance,” allowing operators to take cells offline and avoid potentially catastrophic outcomes like Moss Landing, Woodward said.

This capability is particularly important for second-life battery installations, where individual modules “are already in a state of divergence,” Woodward added. Element has nearly 2 GWh of used electric vehicle batteries in inventory and in November deployed about 900 of them to create the world’s largest second-life stationary storage installation, a 53-MWh facility in West Texas.

Dramatic improvements in lithium-ion battery safety require fundamental changes to battery management and architecture, said Jon Williams, CEO of Viridi.

UL 9540 and UL 9540A are “observation standards based on putting the technology into failure mode … not an acknowledgement of safety [but rather] what you can do to avoid burning everything down,” he said.

Viridi’s mobile and large-scale lithium-ion battery systems have a “defense in depth” approach that uses the company’s proprietary “fail-safe anti-propagation architecture” alongside other physical and software-based safety systems, according to a presentation shared by Williams. A Viridi 50-kWh battery pack has a predicted failure rate of 1 in 158.5 GWh, compared with 1 in 3.3 GWh for traditional BESS, Viridi says.

Viridi’s systems cost more than standard BESS, but “over the full lifecycle, it’s more cost-effective not to have to build more ventilation and fire suppression,” he said. “It’s also cheaper to run diesel engines with no emissions controls, but we acknowledge that there is more cost embedded in that emission than just the fuel and hardware.”

In the longer term, efforts to develop solid-state lithium-ion vehicle batteries by automakers like Toyota and technology developers like QuantumScape could benefit the stationary storage industry, said Ric O’Connell, founding executive director of GridLab. That’s because stationary storage is a “technology taker” dwarfed by the electric mobility industry, which is likely to continue driving battery innovation.

“You can’t afford to build a technology just for stationary storage,” he said.

Is 2025 the year for electrochemical alternatives?

Some non-lithium battery technology companies would disagree.

“[Moss Landing] has been a disruptor for the energy storage industry in general [and offers] an opportunity to highlight the alternatives to lithium-ion batteries,” said Giovanni Damato, president of CMBlu Energy’s U.S. subsidiary.

With no high-toxicity materials, almost 50% water in its active chemistry and better performance in extreme weather conditions, safety is a key part of Damato’s pitch for CMBlu’s organic flow battery systems. The modular systems also scale well, making them economical at durations longer than four hours, Damato told Utility Dive last year. And the supply chain is straightforward to localize thanks to off-the-shelf modules and a polymer-based chemistry that can be sourced wherever plastic feedstocks are available, he said this month.

CMBlu recently secured funding to build a 4-GWh factory in Greece that it aims to commission next year, followed by a “copy-paste” production facility in the United States, Damato said. In the meantime, it’s running at least two utility pilots: a 5-MW/50-MWh deployment for Arizona’s Salt River Project and a “1-2 MWh” installation at a WEC Energy Group cogeneration plant in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

The Wisconsin deployment sits “just feet away from the boiler unit, so that gives you an indication of what they think the safety profile is,” Damato said.

Utilities and other customers are piloting other non-lithium battery technologies as well. In September, the Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians and the U.S. Department of Energy Loan Programs Office closed on a $72.8 million loan to build out a microgrid pairing 15 MW of solar with 10 MWh of vanadium flow batteries and 60 MWh of aqueous zinc batteries. Form Energy — another Prelude Ventures portfolio company — is demonstrating its 100-hour iron-air battery system with utilities in California, New York, Washington and Minnesota.

Outside the U.S., sodium-ion chemistry is making inroads into the Chinese battery market thanks to a growing cohort of homegrown technology developers and manufacturers, said Cam Dales, cofounder of Peak Energy, which aims to produce and deploy sodium-ion batteries in the U.S. at utility scale.

NFPP, a variant of sodium-ion battery similar to the lithium-iron-phosphate chemistry popular with American BESS developers, “is fantastically suited to stationary storage,” Dales said. Peak is targeting its first deployments with U.S. utilities and independent power producers this year and intends to stand up the country’s first gigawatt-scale sodium-ion battery factory in 2027, according to its website.

Sodium-ion chemistry is less energy-dense than lithium-ion, trading higher stability — and lower risk of thermal runaway — for lower space efficiency. In addition, the U.S. happens to have one of the highest-quality, lowest-cost sources of raw sodium in the trona fields of Wyoming, Dales said, potentially mitigating supply chain risk as trade tensions rise between the U.S. and China, which continues to dominate the lithium battery supply chain.

Sodium-ion batteries also have “drop-in compatibility with Li-ion manufacturing infrastructure,” which “suggests rapid scaling timelines,” Stanford University researchers Adrian Yao, Sally Benson and William Chueh said in a study published last month. But the technology might not be cost-competitive with lower-cost lithium-ion variants until sometime in the 2030s, “assuming that substantial progress can be made along technology roadmaps via targeted research and development,” they said.

An August analysis by DOE likewise cast doubt on sodium-ion’s near-term cost-competitiveness, projecting 2030 costs between $0.23/kWh and $0.553/kWh against $0.067/kWh to $0.143/kWh for lithium-ion.

Dales is more optimistic, predicting sodium-ion batteries would reach cost parity with LFP at the cell level by 2027. And sodium-ion chemistry promises significantly lower 20-year cost of ownership thanks to a simpler balance-of-system, higher round-trip efficiency and “a long list of improvements that the chemistry enables,” he said.

“There’s a lot of chatter across the industry based on incomplete information,” Dales said. “Even today, [NFPP] wins by a large margin on cost at the project level.”

But as lithium-ion battery prices continue to fall and system safety improves, the technology could prove difficult to dislodge, at least in the energy storage industry, Woodward said.

“We’ve tried in the past to invest on the thesis that people will say lithium is not safe, and it just hasn’t happened,” he said. “[Lithium] keeps coming down the cost curve and will keep getting deployed as people find ways to minimize the risk.”