Mandate innovations should no longer be limited to megawatts of wind and solar.

State mandates, called renewable portfolio standards (RPS), set a standard for the renewable MWs that state load serving entities (LSE) must have in their portfolios by a specified date. RPSs, mandated in D.C. and 29 states, are at least partially responsible for 56% of the 120 GW of renewables built since 2000, according to Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL).

RPSs were conceived as a means to drive the market for renewables to achieve policy goals like reducing greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) and increasing power system reliability through resource diversity. As the supply of renewables has expanded, states like Massachusetts and Arizona are experimenting with new policies to achieve the same goals in new ways.

Ideas like Massachusetts' Clean Energy Standard (CES) and Arizona's Clean Peak Standard (CPS) are gaining momentum as policymakers come to understand the need for ways to evolve the RPS concept.

"The premise that every kWh of renewables will reduce greenhouse gas emissions is just incorrect," V. John White, executive director for the Center for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Technologies, told Utility Dive.

Megawatts and the RPS

The power system is being transformed from reliance on coal and nuclear generation to reliance on natural gas and utility-scale renewables. That transformation is driven primarily by low natural gas and renewables prices, but the mandates that drove renewables prices down are, despite their success, being reconsidered.

There have been many efforts to repeal, reduce or freeze RPS mandates. Only two succeeded, and Ohio's mandate was reversed, LBNL reported.

The price of natural gas fell due to abundant new supplies. But it was market-driving policies, primarily state renewables mandates, that dramatically grew the installed capacities of wind and solar after 2009. The result was a 38% drop in wind's contract price and a 77% drop in solar's contract price, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finances.

Climate mitigation and health benefits from RPSs are "in the $3 billion to $4 billion range," Breakthrough Institute energy and climate analyst Jameson McBride told Utility Dive. That "significantly outweighs" the roughly $1 billion in implementation and compliance costs.

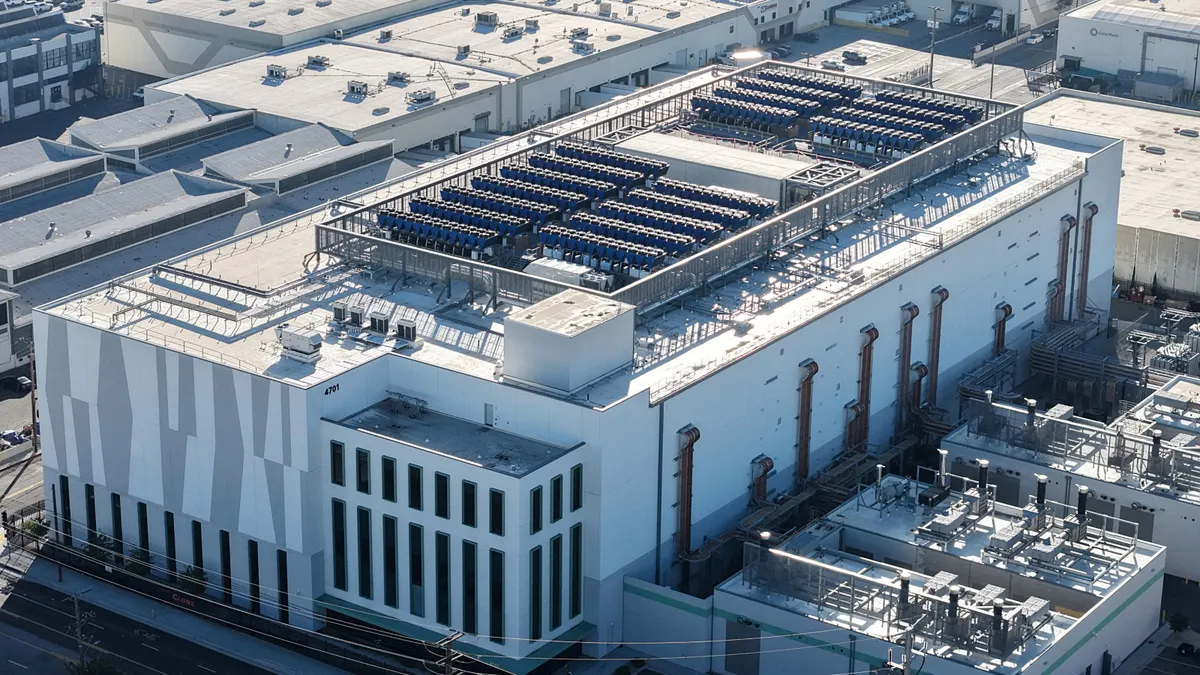

For example, while California has 11.4 GW of solar and 6.3 GW of wind, the state's goal to "just build MWs" should shift focus to servicing the grid and meeting the state's climate goals, CEERT's White said. The group was among the main advocates that pushed for California's original renewables mandate and for its current 50% by 2030 law.

Searching for solutions, policymakers proposed 181 changes to RPS laws in 2016 and 2017. Only 13 were enacted.

"RPSs are definitely succeeding," Clean Energy States Alliance (CESA) Executive Director Warren Leon told Utility Dive. There is strong evidence they played an important role in the growth of clean generation and in driving down costs. But they are changing and the future of the RPS may be very different."

RPS goals can focus on MW of new renewables, but can also include environmental, economic or technology development objectives, CESA found. Simplicity, specificity, cost-effectiveness and predictability are key to an RPS, according to the group. CESA determined that an effective mandate, targets, goals and rules should be achievable in the allotted time, and monitoring of LSE compliance is necessary.

Over time, RPSs have become increasingly varied, Leon said. It is possible for states rich in wind or solar "to outgrow the need for an RPS." It is also not "the total solution for decarbonization," he added. "It helps make significant progress in one sector of the energy market and that is all it was intended to do."

Several states have moved to a Clean Energy Standard (CES) that includes things like energy efficiency, fuel cells or nuclear power, he said.

"If the supply of qualifying electricity is increased and the demand is not increased, that will crash prices for renewables and nuclear," Leon added.

An RPS design study for the peer-reviewed journal Nature, found that a mandate's "stringency" increases renewable energy by 0.2%, solar generation by 1%, and energy capacity by 0.3%.

"Stringency is how high the benchmarks are and how quickly those benchmarks ratchet up," paper author and Indiana University associate professor Sanya Carley told Utility Dive. In 2014, the last year assessed by the paper, Hawaii had the most stringent standard, followed by Ohio, Michigan, Kansas and Colorado.

An RPS must be ambitious enough to not constrain the market, but not so ambitious that the goal is not achievable, Carley said. The next most important factor for an RPS's success is ongoing planning for transmission expansion and renewables integration, she said. That assures renewables developers that the generation they build can be marketed.

Non-mandated goals and voluntary targets are not effective "except where the resource is so strong it is price-competitive, like wind in the Great Plains states," Carley said. "If it is the least cost resource, it will be chosen, whether there is an RPS or not."

States also need to be cautious about experimentation, Carley found. Although few states have special provisions for non-renewables, such as nuclear and clean fossil generation, those states "do not produce any more or less renewable energy than those that do not," Carley said.

Beyond megawatts — the CES

Federal action on climate change seems unlikely for the remainder of the current administration, a Third Way and Breakthrough Institute paper observes. But a CES that includes "renewables, nuclear, carbon capture and other low-carbon sources" can be a way to get to "more ambitious targets for decarbonization."

"A CES works the same way as the RPS," McBride told Utility Dive. "It is the same thing but more."

At present, New York, Illinois and Massachusetts have leading CESs. Massachusetts' standard for 2050, requiring 80% clean energy and 45% renewables, is the best because it assures an increase in renewables and in clean energy, McBride said.

Some CESs include tradable zero emission credits (ZEC), he said. Like the renewable energy credits (REC) that utilities must acquire to meet their RPS obligation, utilities acquire ZECs to meet their CES obligation. Unlike the other two states, Massachusetts ZECs do not support existing nuclear generation.

To reduce GHG emissions, the RPS focuses on the "means" of specific technologies, MIT Energy Initiative analyst Jesse Jenkins told Utility Dive in an email. The CES is more flexible because its focus is on "ends" of "reducing emissions of CO2 and other pollutants in the power sector."

That greater range of resources available through a CES makes it a more politically viable policy in states that have rejected RPSs, the paper reports.

CESs could preserve the one-fifth of U.S. generation now supplied by nuclear power plants, McBride said. And, because shuttered nuclear plants are often replaced by natural gas generation, "failing to preserve them could cancel out almost all the recent U.S. GHG reductions from wind and solar," he added.

The CES is not enough of an incentive to make new nuclear viable in the U.S., McBride said. But it would be a market signal to nuclear developers that a cost-competitive technology approved by regulators could have a role in future "deep and complete decarbonization."

There are risks with nuclear energy, he acknowledged. "But it should be reconsidered for its climate benefits."

In the near-term, "the vast majority" of resources needed to meet a CES would come from wind and solar, Jenkins said. But at high penetrations, a CES could allow those variable resources to be balanced by "'firm' or 'dispatchable' low-carbon energy resources," including renewables, like bioenergy and geothermal, as well as non-renewables, like nuclear and carbon capture technologies.

Getting to 100% decarbonization through renewables, as proposed by Stanford Professor Mark Jacobson, would require significant battery energy storage and an over-building of renewables, McBride said. Jacobson has inconclusively debated scientist Christopher Clack about the cost-effectiveness of his proposal, but McBride said the cost of battery storage makes it "not yet a complete solution."

Jacobson and others say the costs for renewables and battery energy storage are coming down so fast that they are offering solutions never thought practical before, like the CPS.

The CPS and the peak

The newest innovation in clean energy mandates may be a more cost-effective way of taking advantage of battery energy storage.

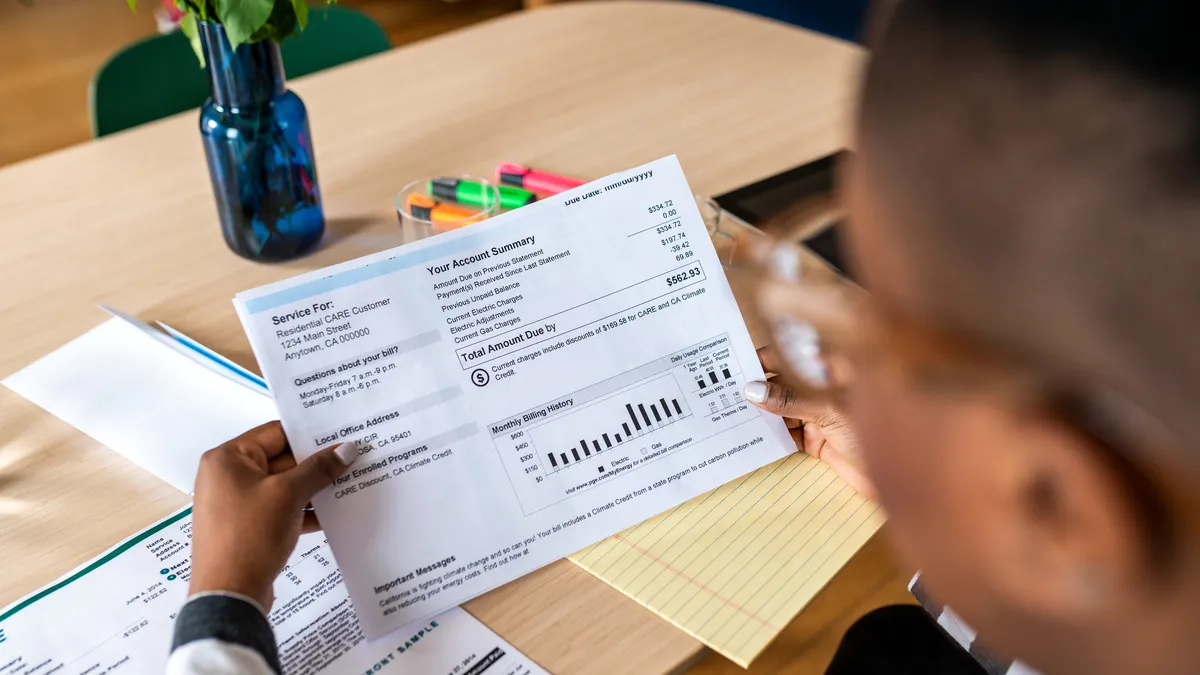

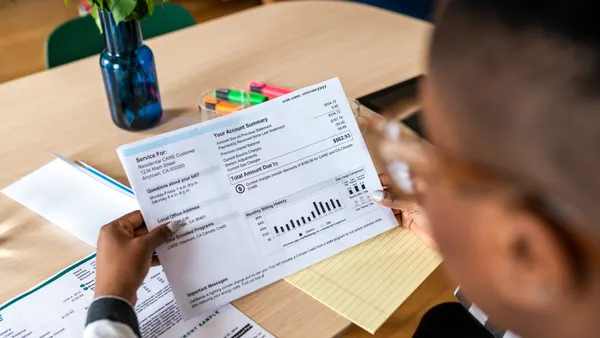

"States thinking about what the next step in clean energy policy is should begin by asking what produces the most value to ratepayers," Navigant Director Lon Huber told Utility Dive. "Any new renewables policy should be shaped around the answer."

"[The CPS] opens up new opportunities to address today's greatest energy challenges like enhancing reliability and resiliency on the power grid and meeting peak energy demand without the need for new fossil generation."

Kate McKeever

Director of regulatory affairs, Enel Green Power

That question led Huber to design the Clean Peak Standard (CPS). And it is the high cost to customers for meeting spiking peak demand that led Arizona, California, Massachusetts and New York to take an interest in Huber's 2016 white paper introducing the CPS.

The CPS expands a state's RPS by adding a mandate requiring a portion of its peak demand to be met by renewables, accomplishing "two things with one policy," Huber said.

"It adds more renewables, but it adds them when the system most needs capacity," he said. "That means it uses renewables to deal with system cost drivers and saves ratepayers money when electricity prices are highest."

The CPS "opens up new opportunities to address today's greatest energy challenges like enhancing reliability and resiliency on the power grid and meeting peak energy demand without the need for new fossil generation," Kate McKeever, Enel Green Power director of regulatory affairs, emailed Utility Dive. "It will drive deployment of resources like renewables and storage."

On July 31, Massachusetts lawmakers passed H.4857, which adds a CPS to the state's mandates. The CPS requires a "minimum percentage of kWh sales to end use customers from clean peak resources." Specifics were left up to regulators.

Arizona regulators are currently reviewing a CPS proposal. California's proposed CPS was negotiated out of Senate Bill 338, but advocates protected language requiring utilities to consider how energy storage and other zero emissions resources can replace natural gas generation in meeting peak power needs. And New York regulators are considering the CPS to address capacity needs in supply-constrained localities.

"We expect more states in the coming legislative sessions to tackle these issues," Huber told Utility Dive. "There is no point in increasing an RPS to 50% just because the Jones are doing it. Now that we have storage and advanced inverters, we need to do things we never thought possible before. We can now think bigger about renewable energy strategies."