Illinois regulators unanimously approved the Rock Island Clean Line that promises to cut power bills by delivering low-priced, wind-sourced electricity from Iowa for distribution throughout the East.

The green light is also good news for the same developer’s controversial Grain Belt Express that would deliver wind-generated electricity from Kansas to eastern markets.

By a 5-0 vote, the Illinois Commerce Commission granted developer Clean Line Energy Partners (CLEP) a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity for Rock Island. The approval will allow CLEP to go after the rights of way and financing necessary to build the Illinois portion of the $2 billion, 500 mile high-voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission system.

The line must still be approved by the Iowa Utilities Board, a decision CLEP hopes to get before the end of 2015.

If completed, Rock Island would carry up to 3,500 megawatts of electricity generated in wind-rich northwestern Iowa to a station just west of Chicago, explained Sean Brady, Wind on the Wires Regional Policy Manager. There, that electricity could be dispersed through the PJM Interconnection to denser populations with less access to wind from Ohio and Pennsylvania to Virginia and Maryland.

The line’s impact on the supply-demand balance in electricity markets could cut “the annual cost of wholesale electricity used to serve Illinois customers by an estimated $320 million in its first year of operation,” according to CLEP. It will also bring Illinois an estimated $600 million in direct investment and hundreds of temporary construction jobs and longer-lasting transmission and wind sector manufacturing and operations-and-maintenance jobs.

The Grain Belt Express

Transmission advocates say many of the same benefits would go to states along the path of CLEP’s Grain Belt Express, a proposed $2 billion, 750 mile, HVDC system that would move 3,500 megawatts of Kansas wind-sourced electricity eastward. A 500 megawatt portion would be delivered to a station in Missouri, where regulators will soon rule on CLEP’s plan.

Grain Belt already has approval from Kansas and Indiana, where it terminates. If Missouri approves, CLEP will go before the ICC again, Brady said.

“It makes a lot of sense to build wind where the costs are low and use transmission to get it to areas that don’t have good wind,” said Geronimo Energy VP and former Xcel exec Betsy Engelking. “But it is very difficult to get projects like the Clean Lines built because they cross state jurisdictions.”

Dealing with both state permitting authorities and public opposition can be daunting, she explained. “I have seen cross-jurisdictional planning end up with lines at different places where they are supposed to meet to cross a river.”

The keys are making a strong case to the permitting authorities and convincing the public that the line is needed, Engelking said. “It is a great idea and bless them for trying.”

Opposition from the local utility

Commonwealth Edison (ComEd), the regulated utility subsidiary of Exelon in Illinois, filed representative opposition to Rock Island during the ICC deliberations. It described CLEP as “a single-purpose thinly-capitalized private venture entity," and described the Rock Island proposal as a “speculative plan.” It argued against the project’s approval because it said CLEP did not show:

- the project “is necessary to provide adequate, reliable, and efficient service”

- CLEP “is capable of efficiently managing and supervising the construction process”

- CLEP is capable of financing the proposed construction

“The project is ‘a Field of Dreams,’” ComEd asserted. Though CLEP “may hope that ‘if we build it, they will come,’ that is not what the law requires.”

“Our lines are participant funded,” explained CLEP CEO Michael Skelly. Financing will not be certain until the lines take on subscribers. “But if you are a wind farm and you want to get to market, you will buy a little slice of our capacity to move your power.”

In its final order, the ICC decided "assessment of the issue at hand is complicated by the many unknowns associated with the ‘merchant’ nature of the proposed transmission project.” But, it added, CLEP adequately addressed the “pertinent concerns.”

CLEP has a satisfactory construction management organization that it can fill out if and when a final route, rights-of-way, and financing are completed, the ICC found. It did, however, make CLEP's final right to proceed subject to obtaining “commitments for funds in a total amount equal to or greater than the total project cost.”

Unlike ComEd in Illinois, Ameren and Kansas City Power & Light did not intervene in Missouri, Skelley noted. “Most utilities recognize that we need to do a better job building the U.S. grid. They are typically the last to object to new projects. But ComEd owns a lot of assets and a new entrant to the market could affect prices.”

Opposition on the basis of need

In assessing the Grain Belt Express in Missouri, a Missouri Public Service Commission staff report found that while CLEP demonstrated abilities to finance and build the project, it had not “established the need.”

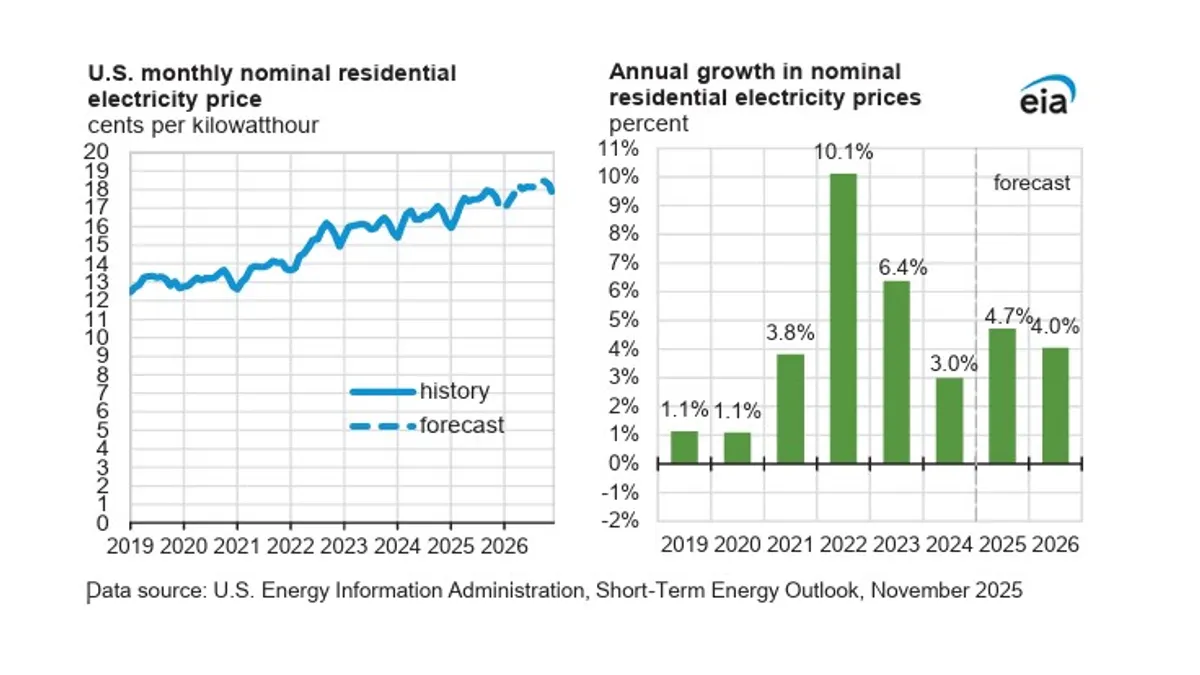

The need for either line comes down to economics, according to Skelly. The estimated price of wind-generated electricity from Kansas or Iowa delivered to PJM or to the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) is estimated at $0.045 per kilowatt-hour or less. That includes the cost of the electricity and the transmission fees. It is expected to be competitive with the projected $0.057 per kilowatt-hour electricity price in those markets, he explained.

Adding 3,500 megawatts of generation will create competition that will drive prices down further and cut ratepayers’ bills, Skelly added. And the proposed EPA Clean Power Plan will drive still greater need for renewables in PJM and MISO states.

Opposition to granting eminent domain authority

There is another objection to the lines in both Iowa and Missouri.

Grain Belt Express “does not merit certification” because neither its purpose nor its potential benefits to Missourians “justify the authorization to exercise eminent domain power,” asserted the Missouri Farm Bureau. “Potential benefits are outweighed by the concerns expressed by many of Farm Bureau’s members.”

Without eminent domain authority, Engleking said, they have to find landowners willing to grant easements. "Getting route approvals is where the rubber meets the road,” he said.

Producing a final route is the big challenge ahead of CLEP once all state approvals are obtained.

Rights-of-way

The goal is obtaining rights-of-way “through negotiations with landowners and voluntary transactions, to the maximum extent possible,” Skelly said in his ICC testimony. To do that, CLEP offers “effectively the whole market value” for a 150-foot wide to 200-foot wide easement, he said. It also promises a yearly fee to owners of land on which a tower is built as well as payments for other impacts.

Like infrastructure projects such as pipelines, telephone lines, and electricity lines, Skelley said, CLEP “may seek to acquire certain easements through condemnation, but only as a last resort after exhausting all reasonable attempts at voluntary easement acquisition.”

“They will get their rights-of-way,” Brady said. “The standard is typically the shortest, most direct route.” If there are obstacles, the standard becomes the shortest route that avoids them. “The route ends up getting moved one way or another to find the most cost-effective route.”

Brady would not predict eminent domain would not be used. “The likelihood is directly proportional to the number of landowners you need to negotiate with,” he said.

“What we are talking about is not impossible,” Engleking said. “The hurdle is the sheer size of the convincing they have to do.”

Editor's Note: This is the ninth piece in an ongoing Utility Dive series on new high voltage transmission. Other installments in the series are:

What happened to that national high voltage transmission system? Clean Line and others are still pioneering lines for remote renewables.

Can Warren Buffett's Pacificorp bring the Northwest's renewable riches to market? The Energy Gateway will change the way America uses energy — when it gets finished.

How new transmission will bring Wyoming wind to California: President Obama’s transmission plan aims to bring remote renewables to load centers.

How to build high voltage transmission in America: Projects are struggling with permitting across the country, but PSE&G and PPL got it done.

Is SunZia ready to deliver New Mexico wind to Phoenix and Los Angeles? After years of fighting for permits, SunZia is about to get a green light—or a lawsuit.

Idaho Power's vital Boardman-to-Hemingway transmission line wrestles with permitting; Instead of delivering renewables, it’s struggling over sage grouses and ground squirrels.

One grid to rule them all: Is a national transmission system coming to America? A bold idea to interconnect the nation’s three grids is just a financing agreement away

Grid of the future: How transmission and new technologies can work together; Ex-FERC Chairman: "We may get to the point where we don't need a network of wires. But I can't foresee that."