Microgrids have typically been considered a resilience solution, but increasingly they can also help to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and should be considered as options in a flexible energy portfolio, according to research from two non-profits focused on state policy.

The National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners and the National Association of State Energy Officials jointly issued the report last week examining the capabilities, costs and benefits of microgrids, as well as digging into deployment strategies and barriers to their development.

“Ensuring energy resilience and meeting state decarbonization goals are two major challenges that state regulators are tasked to address,” NARUC Executive Director Greg White said in a statement. The report aims to assist state public utility commissions “grappling with these interrelated topics,” he said.

“Clean energy microgrids can provide both benefits simultaneously and even decrease overall emissions when replacing diesel or natural gas backup supply or large-scale fossil fuel generation,” the report said. Backup generation fueled by fossil fuels can be particularly dirty, but when paired with renewables on a grid-connected microgrid that system could potentially earn renewable energy certificates.

“This could alleviate reliability concerns of microgrid customers considering variable renewable energy sources for a microgrid, particularly without a battery system, and allow for a gradual emission reduction until further energy storage or non-variable clean energy generation sources are installed,” the report said.

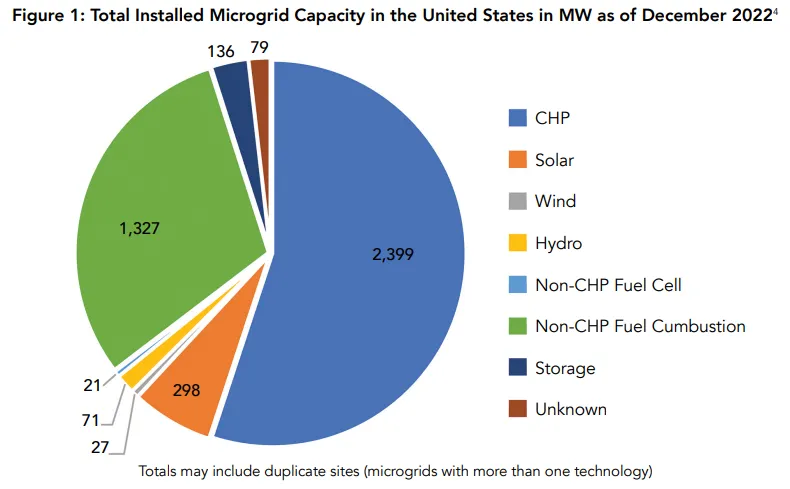

The most common microgrid technology is combined heat and power, where electricity and useful heat are produced from the same fuel source.

While nuclear energy has not been a generation source for microgrids, “new small modular reactors have the potential to provide carbon-free energy to microgrids in the future,” the report notes.

Microreactors, with capacities often ranging from 1 MW to 20 MW, “are likely to be deployed in the near term” though the report notes that the timeline is uncertain. Some experts estimate microreactors will be ready for deployment “either for remote or grid-connected pilot projects in the next 3 to 4 years, and others seeing a slightly longer timeframe — until 2030 for pilot projects and commercial development between 2030 and 2040.”