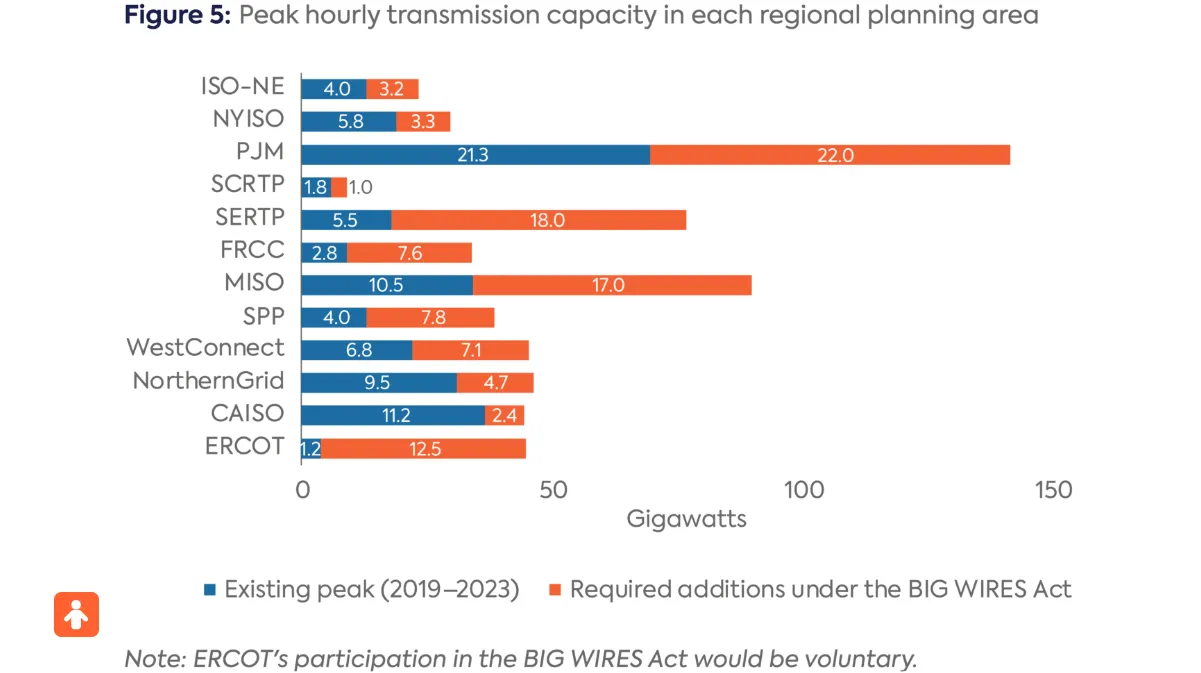

Interregional transmission transfer capacity in the U.S. would more than double to 191 GW in 10 years from 84.4 GW today under the BIG WIRES Act, according to analysis released Tuesday by researchers at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University.

The bill — introduced in September by Sen. John Hickenlooper, D-Colo., and Rep. Scott Peters, D-Calif. — is one of several potential catalysts that could lead to an expansion of transmission capacity between regions, said Abraham Silverman, the center’s director of the Non-technical Barriers to the Clean Energy Transition initiative and one of the report’s authors.

In addition, there is a growing recognition of the benefits of increased transmission capacity, such as reducing costs and allowing neighboring regions to share electricity during extreme weather, according to Silverman, formerly the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities’ general counsel.

The BIG WIRES Act directs the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to set minimum interregional electricity transfer capacity requirements within 18 months of the bill becoming law. Regions would then have two years to file plans at FERC describing how they would meet the transfer requirements by the end of 2035.

“The BIG WIRES Act process addresses several of the issues bedeviling today’s transmission planning processes: the lack of a ‘venue’ for regions to engage in planning, uncertainty on how costs would be allocated, and designating who builds the infrastructure,” the report’s authors said.

The bill would require FERC to set a region’s transfer capacity at 30% of its peak load or at its peak transmission plus 15% of its peak load, whichever amount is smaller.

Under the bill, the Southeast would see the largest percentage increase in transmission, according to the analysis. The Southeastern Regional Transmission Planning area would need to increase its transfer capacity by 18 GW from 5.5 GW and Florida would need to add 7.6 GW to its 2.8 GW of transfer capacity, the researchers found.

To meet the bill’s requirements, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas — which is outside FERC’s jurisdiction — would need to build 12.5 GW on top of its 1.2 GW of existing transfer capacity, according to the report.

Although a minimal amount of interregional transmission has been built in recent years, there is a growing consensus it is needed and there are several pathways to building it, according to Silverman.

Besides mandates, such as those in the BIG WIRES Act, Sen. Martin Heinrich, D-N.M., last year introduced a bill that directs FERC to require interregional transmission planning, Silverman said. FERC commissioners have indicated the agency could take up interregional transmission planning after it issues a pending rule revising the intraregional planning process.

The Department of Energy and FERC are also advancing new rules for building power lines in designated transmission corridors, Silverman said.

Meanwhile, 10 Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states, including Maryland and Delaware, are exploring how they can increase interregional transmission capacity between themselves, Silverman noted.

“All of these various legislative proposals and these various plans that people are pushing forward, all come back to solving the real problem that we just don't have an interregional planning infrastructure at the moment,” he said.

Silverman said he is optimistic that a solution to the lack of interregional transmission development will be found, in part because there is a growing recognition of its economic benefits and the growing risks of extreme weather.

“You have an increasing realization from across the political spectrum that we need to do something,” he said. “Once that consensus exists, it's only a matter of time.”

Congress could act on transmission and permitting reform this year, possibly during a lame duck session after the election, according to Silverman. But, even if nothing gets passed, at a minimum, work in Congress this year could pave the way for action in future Congressional sessions, he said.