After enjoying great fanfare last decade, concentrated solar power has gone out of vogue lately in the power sector, eclipsed by the rapid cost declines and proliferation of photovoltaic systems. But while the technology remains more expensive than PV in head-to-head comparisons of PPA price, a slate of new projects coming online with energy storage and dispatchable power capabilities points to a new way forward for the sector.

The technology is called concentrated solar power because the facilities take energy from the sun and focus it to produce heat, explained Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD) Senior Project Manager Bud Beebe, the moderator of a CSP Panel at Solar Power International 2015 (SPI), the recently-concluded annual solar conference.

“It may be more accurate to describe it as taking energy from the sun and making it into stored high temperature heat energy that can be used for, among other things, generating electricity," he said.

The three solar-to-steam towers that make up the 377 MW BrightSource Energy (BSE) Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System are now providing electricity to Southern California Edison and Pacific Gas and Electric. The 280 MW Solana trough project with six hours of molten salts storage, built by Abengoa Solar, is sending electricity to Arizona Public Service (APS), and the 110 MW Crescent Dunes solar power tower with ten hours of molten salts storage will start sending generation to NV Energy next month.

With the long-overblown question of harms to migrating birds resolved by documentation showing the facilities have low to no biological impacts, the pioneering companies' attention has turned to their real challenge.

“The biggest challenge U.S. CSP has, even with storage, is price," explained SolarReserve CEO Kevin Smith.

"PV prices have dropped dramatically and the U.S. has a very well built-out generation and transmission system with lots of baseload generation and lots of peaking power, so the value of storage has not been fully realized," he said. "That is why we are moving into other parts of the world.”

“We are all looking internationally to places where the disparity between dispatchable and non-dispatchable is better recognized,” agreed BSE Chair/CEO David Ramm. “The ability to shift the delivery of the electricity to when they want it is worth about 2.6 times the underlying rate in South Africa.”

With CSP, Beebe said, the sun's presence and making electricity are decoupled.

“This is not as widely understood as it should be," he said.

A new understanding of concentrated solar

While CSP is the acronym the power industry knows, the technology is more accurately named Solar Thermal Electric Power (STEP) because it takes solar energy to thermal energy and then to electricity, said Abengoa Solar Managing Director Fred Redell.

“It is what you do with it while it is thermal and where you put it later that really matters," he said.

New opportunity will emerge for the technology as utilities and grid operators begin to understand the implications of the STEP name by which the technology was known in its earliest days of development.

The solar photovoltaic (PV) panels being built on homes and businesses across the country and around the world at a record pace transform the sun’s light into electricity. STEP uses mirrors called heliostats to concentrate the sun’s heat on a focal point. Molten salts passing through the focal point are heated to 1050 degrees Fahrenheit and stored in a hot tank.

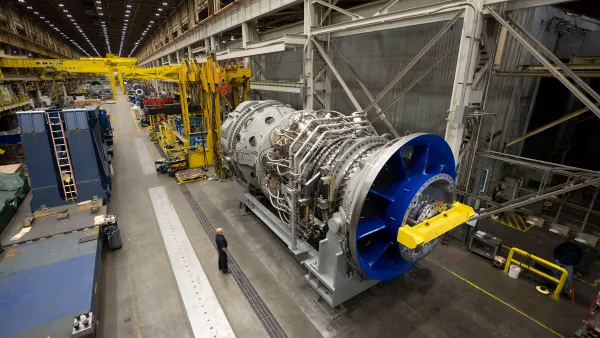

When power is needed, the heat in the salts can be transferred to water in a heat exchanger, creating steam to drive a turbine that generates electricity. The salts then flow back to a cold storage tank to await recirculation through the closed system.

Off-takers not only need to understand a facility’s nameplate capacity and hours of storage, “but also that it is decoupled from the resource,” Redell said. “You could configure a project to deal with just the peaks. You could also configure it as just a baseload product. That capability is because of the storage component."

This is important, Redell added, because prospective off-takers can then begin to understand how the cost changes depending on how decoupled it is from the resource.

Beating the Duck Curve

Until now, utilities have met renewables mandates with "just renewables," without considering when or how they'd be used, Beebe said. But going forward, utilities will need to pay attention to renewables that are “there when the electricity demand is there."

If the only criteria in a state renewables mandate is energy cost, “you will always bias in favor of intermittency, which puts more intermittency on the grid and makes some of the intermittent energy not worth very much,” Ramm said.

High levels of PV acquired to meet a mandate can contribute to a problem the California grid operator calls the Duck Curve.

In the late afternoon, “PV starts to fade, and demand ramps up,” Smith explained. “You can handle that with conventional energy, with batteries tacked on the back of PV and wind, which is expensive, or with solar thermal with storage.”

“Or like they do in South Africa with rolling blackouts,” Ramm joked.

But the Duck Curve offers the opportunity to do “something else” with concentrated solar power, Redell said. It can continue to provide baseload energy, but it can also provide electricity when the sun is not shining to help manage the Duck Curve ramps.

Studies from NREL and LBNL show issues that come from high penetrations of PV and wind can be alleviated by solar thermal with storage, Beebe noted.

Flexibility

Think about a grid operator managing a system in a regulatory environment that promotes intermittent renewables to an extreme, Ramm said. That grid operator has to account for all the intermittency.

Grids are getting smarter and spreading resources across large grids can be helpful, he said, "but all that intermittency requires economic choices."

Grid operators have to take and pay for the intermittent resources. "But they also have demand curves and intermittent renewables may not satisfy them," Ramm said.

STEP gives the grid operator a renewable resource that comes with the choice of using it on a continuous basis or storing for a peak demand period or using part of it and holding back part of it.

“It provides choice without penalizing the grid operator," Redell said, and also adds no serious complexity for the grid operator.

APS sees and uses the full value of the Solana STEP project, Redell explained.

“It was designed specifically to meet both their summer and their winter needs," he said. "They have a dual peak need in the winter and an extended peak need in the summer.”

Because Solana has extra generation in the summer and adequate generation in the winter, “they have seen the value in the product’s ability to do both those things.”

Crescent Dunes is expected to be used by NV Energy to meet the Las Vegas noon to midnight demand, Smith said. “The storage capability is why they chose us in their bidding process.”

Integrating the 110 MW Crescent Dunes generation into NV Energy’s nearly 600 megawatts of utility-scale solar is not expected to be “overly significant or troubling,” said NV Energy Communications Director Mark Severt. “It will flow initially on our 230 kV system in Northern Nevada and then the 500 kV One Nevada Transmission Line will carry its production to our customers in the Las Vegas area.”

If a utility has no need for STEP’s capacity or ancillary services, which appears to be the case for NV Energy with Crescent Dunes, it can use the stored energy like baseload generation, Redell said. Because STEP has flexibility, “it is about the nuance of fitting the product to the utility’s needs.”

If the utility develops a peak demand need further on and has no need to meet a renewables mandate, contracting with an existing fossil fuel peaker facility could be the least cost approach. “But if there is a need for new steel, one of the alternatives can be a solar thermal peaker and we think it can be a cost-competitive product against gas turbines,” Redell said.

The competition for STEP

STEP should be compared to conventional energy, not intermittent resources, Smith said.

“It is already cheaper than new-build coal or new-build nuclear," he said. "Natural gas prices are below $3 per MMBTU today but if you look at the price over the next 25 years, it will look different. Internationally, natural gas is much more costly and solar thermal with storage can be the cheapest option.”

Solar thermal with storage is the cheapest non-carbon baseload resource and also the cheapest non-carbon peaker resource, Redell agreed.

Without storage, this technology is not worth much because you are competing against PV which converts sunlight directly and you are at a disadvantage, Ramm said. “But in the energy world technologies are compared on cost competitiveness, and we think our dispatchability is worth $0.05 to $0.07 kWh relative to PV or wind.”

The configuration of the facility really matters to the grid, Redell said. The Abengoa Chile facility was built with 17.5 hours of storage to be used entirely as baseload, but 12 MW of battery storage were designed into the system so stored solar can also provide the grid operator with spinning reserves.

In the U.S., batteries could supply capacity or greater dispatchability.

“You know you have thermal energy in the tank, you know what the day-ahead market wants, and you dispatch it the next day," Redell said. "It is a different way of looking at solar.”

A facility can also be designed to incorporate both STEP and PV, as SolarReserve is doing in South Africa and at other international sites, Smith said. “You run the cheaper PV during the day when the sun is shining and when that ramps down, you ramp up your stored solar thermal. In Chile, it comes out to a cost of less than $0.10 per kWh.”

The developer creates the design with the needs of the utility or the grid in mind, Redell said. Because of the storage, STEP is like baseload generation, but with the added bonus that off-takers can meet renewables mandates with it. But, unlike meeting their mandates with PV or wind, “they don’t have the need to complement it with backup generation.”

Looking ahead

U.S. utilities and grid operators don’t yet have a need to recognize the flexibility of solar thermal with storage, Redell said. “They know what it can do and many are excited about it but it is something completely different.”

The one strong metric is that solar thermal with storage is much cheaper than PV or wind with battery storage, Smith added. “Battery storage is ten times the cost of the storage component of solar thermal and batteries have duration and other issues while molten salts storage lasts 20 or 30 years without replacement.”

Policies that value storage like those introduced in California will be important, Smith said. The main one is primarily for battery storage but a large scale storage mandate is in the works.

More significantly, “California’s new mandate for 50% renewables by 2030 will by definition require storage. They can’t put that much intermittent generation on the system without a lot of natural gas peakers or storage,” Smith said.

Internationally, the cost of natural gas is pushing system operators toward STEP but in the U.S. they are still largely using conventional fuels as backup.

The future of STEP in the U.S. depends on whether or not the value of the storage is recognized, Redell said. “It is dispatchable. It is flexible renewable power. It is ancillary services.”

“Wind and PV lack dispatchability and the visibility of the value of storage is becoming more apparent internationally,” Ramm said. “It will eventually become clear in the U.S. and bring the technology back.”