As utilities and customers look to cut carbon emissions and modernize their grids through the use of distributed energy resources (DERs), one of the nagging questions facing sector stakeholders nationwide is how to decide where, when, and how new technologies like rooftop solar or storage will be deployed on the grid.

New rules are needed, many stakeholders say, to convert the old grid, based on centralized generation, to one that readily integrates and promotes the proliferation of new grid technologies.

A new report from the Public Utilities Fortnightly attempts to address that issue, establishing five principles of "grid neutrality" designed to help utilities and policymakers design a more open grid — one impartial to the technologies being deployed on it, and who owns them.

“We are not being critical of existing grid policies," said Jon Wellinghoff, former chair of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and one of the authors of the study, “Grid Neutrality; Five Principles for Tomorrow’s Electricity Sector."

"We are formulating new policies necessary to optimize operations in a rapidly transforming grid dominated by customer DER acquisition and deployment," he said.

Debates about who should pay for what on today’s grid involve a host of political, business, and technology interests, the paper explains. But the concept of grid neutrality is based on “an inherent structural property of the grid itself.”

Electricity grids are not just conduits of generation. They are dynamic networks, the paper asserts, likening the concept of "net neutrality," which "seeks to maintain a fair and open Internet."

Grid neutrality, by definition, seeks the same thing, "[emphasizing] a fair and open electricity network.”

The extent to which regulators protect grid neutrality is a way “to evaluate future regulatory decisions in the rapidly evolving electricity sector,” said Shayle Kann, another co-author and senior vice president of GTM Research.

Regulatory processes, however, have caused friction in grid policy since they are are based on precedents and past costs that can be backwards-looking, said James Tong, co-author and vice president of strategy for Clean Power Finance (CPF).

Grid neutrality can “steer policies in the right direction,” he said.

For example, Kann said the limited bill reduction for distributed energy resources (DERs) given to customers installing such technologies often fails to accurately value the resource itself.

“Those DERs may have the potential to provide value to the grid, either at the utility level (as distribution deferral, resource adequacy, or another service) or at the ISO/RTO level (as frequency regulation or another service)," Kann said. “With a few notable limited exceptions, this just isn't available to consumers today.”

The grid will be sub-optimal, with consumers overpaying for energy services, until "we reveal values up and down the grid chain, from distribution through transmission and generation, and establish mechanisms to monetize and provide consumers access to those values,” Wellinghoff asserted.

That's a tall proposition, and another nagging question on the sector, but regulators looking for direction today can get their start in the grid neutrality principles, Kann said.

The five core tenets of Grid Neutrality

These five principles encourage empowering the consumer, clarifying boundaries between private and public interests, rewarding risk, ensuring transparency and opening access on the grid.

Allowing DERs onto the grid is an example of the first principle, which calls for enpowering the consumer, according to Kann.

Tong agreed that consumers should have a choice in how they manage their energy.

“We don’t expect every consumer to be a supplier to the grid,” Tong said. “But they should at least have that choice.”

Unintentional bias in regulatory proceedings has historically positioned customers as a uniform and passive block, explained co-author Jenny Hu, a CPF business analyst, but "the world has changed."

“We’re trying to change the language to assume someone wants choice, not that they don’t want it," she said.

Shifting some of the risk and potential reward previously held by regulated utilities to customers who want choice exercises the principles of clarifying boundaries and rewarding risk, according to the paper. Such a move draws a line between public and private interests by rewarding customers who take risks, while also protecting other consumers from the risks taken on by individuals.

These two principles also help ensure that DERs are not over-compensated if utilities more readily or more economically provide the contraptions and include them the rate base, Kann said.

Regulators have, except in rare cases, protected ratepayers from risk and the marketplace from unfair competition by denying regulated utilities the right to rate base residential solar, Tong acknowledged.

But at the same time, a number of utilities have entered the rooftop solar industry either with rate-based pilot programs, such as in Arizona, or through unregulated renewable energy developments arms. Those trends make the risk conversation even more important, Tong said, "because the dialogue in some places has been moving in that direction.”

To follow the fourth principle calling for a level playing field, a customer’s DERs can only be efficiently sited and fairly valued if data transparency exists, the paper argues. And consequently the fifth principle, which calls for open access to the grid, can only occur if the customer can bring DERs competitively to market.

All of that requires a fuller understanding of the value of distributed resources on an individualized basis, the authors said, and grid neutrality is the key to uncovering that information.

“Implementing the tenets of grid neutrality is a condition precedent to accurately valuing DERs,” Wellinghoff said. “Without their implementation in a policy structure, it will be difficult if not impossible to get DER values right.”

Changing the regulation of the past

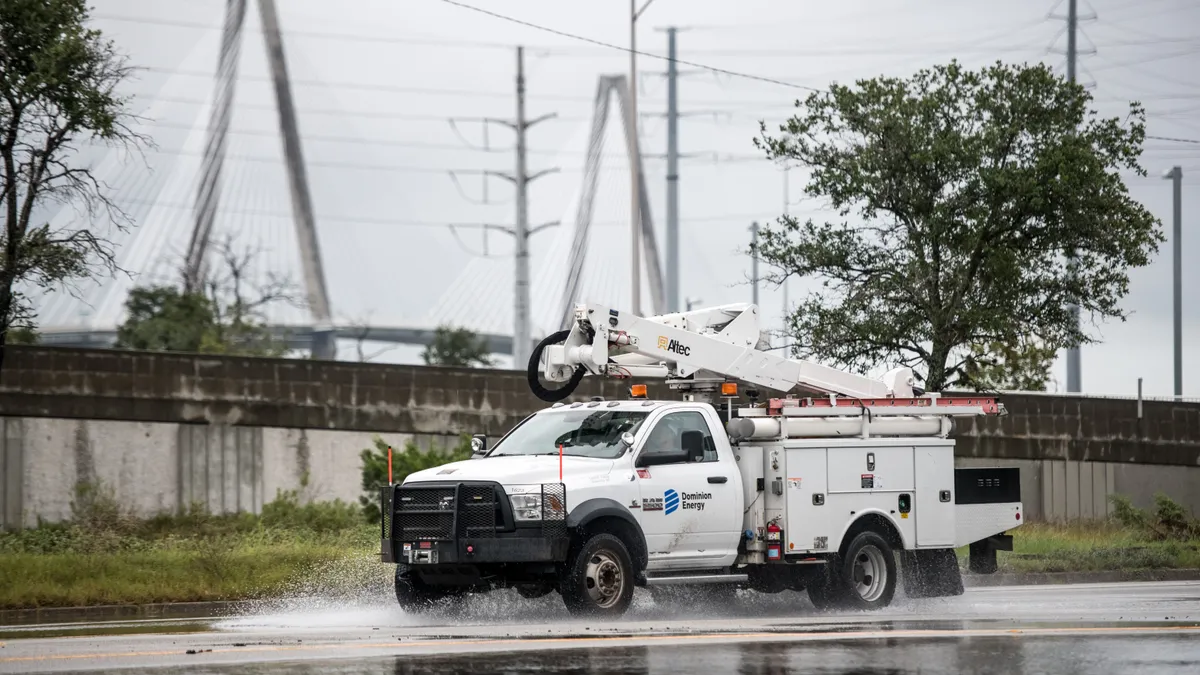

In the past, the power sector has done little to ensure grid neutrality, the paper asserts, especially on the distribution grid, which utilities still largely own as regulated monopolies.

“To take advantage of the enormous economies of scale associated with this grid architecture, governments granted exclusive franchises to monopoly providers," the paper explains. "That ensured a mostly uniform product for captive ratepayers."

That “one-size-fits-all model” doesn’t work anymore for three reasons, the authors argue: New infrastructure is not needed for universal access, and DERs can now often meet grid needs more efficiently than central generation. And the customer is no longer a mere taker from the grid but has in many cases evolved into a so-called “prosumer” by sending energy, capacity, and ancillary services to the grid.

In the last century, regulatory policy evolved for a "monopoly supplier," Tong said.

"Under that construct, everything centers in regulatory proceedings around what the utility does. Regulation is to protect the public from utility excesses.”

The current preoccupation with “the utility of the future” is an example of how today’s grid is not neutral, he said.

“It makes the utilities the center of everything," Tong said. "The center of regulation should be about what is best for the consumer. But in those conversations, the consumer is almost entirely absent. That’s why we put ‘empower the consumer’ as our number one principle.”

For instance, the starting point shouldn't be the prevailing cost of service regulation (COSR) paradigm because it “sets prices based on past costs, not on future potential,” the paper explains. Furthermore, the paper asserts that COSR is also “naturally biased in favor of minimizing harm rather than maximizing customer value.”

This paradigm is inadequate because it requires regulators to subject all grid users to a single interpretation of value. DERs’ value and cost “change constantly in response to locational and real-time constraints of supply and demand,” the paper says. “Setting prices through slow, periodic rate cases cannot keep pace with such a dynamic grid.”

This shortcoming is evident in current regulatory disputes over the value of DERs, the paper added. These disputes appear similar to debates over DER compensation, but the real problem is that the "pricing mechanisms are too blunt and rigid; prevailing regulation cannot dynamically balance the benefits of distributed resources to the grid and grid users.”

Tong added that utilities' integrated resource plans (IRPs) often don't include demand side resources. CPF's Hu agreed that the IRP process should include anyone who meets minimum grid standards, including consumers, utilities, or generator.

“They should be evaluated under the same metric without preference," she said. "And if somebody invents a new energy technology tomorrow, it would be evaluated on the same metric.”

Grid neutrality, Hu added, is “a call to create that kind of metric.”

Hitting all five points in Con Ed’s BQDM project

Consolidated Edison’s Brooklyn/Queens Demand Management (BQDM) Program is a good example of a project that hits all five points of grid neutrality, the authors said.

The utility and the New York Public Service Commission (PSC) “are laying out the framework for that metric but they have not created it," Tong said.

High electrical demand growth in Brooklyn and Queens meant ConEd faced a 69 MW overload of feeders serving two substations by 2018.

The traditional answer would have been a $1 billion-plus investment in new substations, feeders, and switching stations. But ConEd added a request for proposals (RFP) for demand side resources.

ConEd's $200 million-plus proposal to the PSC was for 17 MW of infrastructure investment and for the BQDM Program, which was 52 MW of demand side solutions on both the utility and customer sides of the meter. This was a plan following the five principles, according to the paper.

The BQDM empowered customers who wanted to provide demand side resources while the infrastructure build respected customers’ right to not buy in. The utility's decision to deploy both centralized and customer-side solutions "upholds the dual mandate of grid neutrality."

"It maintains grid reliability while maintaining the grid’s position as a platform via which customers are incentivized to reduce costs for all grid users," the paper explained.

ConEd will own and control the monopoly infrastructure, with most of the distributed solutions owned by customers and/or third parties. This enabled the utility and the PSC to “established clear boundaries for monopoly and market activities [and] protected the rate base.”

For the infrastructure investment, the PSC granted a regulated rate of return plus a 100 basis point reward for the programs built toward its customers. But the PSC denied ConEd’s request for a 50% share of BQDM customer savings. Instead, the agency returned the savings to the customers and third parties who owned the demand side resources. This follows the third principle by allocating various risks and rewards “among various willing and able participants.”

The PSC required the ConEd RFP to be transparent and ordered an independent third party monitor. It also required a public report on the bidding and will require “future public reports on all program expenditures and activities.” These moves augment grid neutrality as defined by the paper.

The RFP and bidding have been open with decisions based on merit, which allows "different technologies and stakeholders to prove their merit ensures an open playing field and upholds grid neutrality,” the paper said.

In meeting all five core principles, the BQDM program should “stand as an early example of the grid operating as an open, transparent platform.”

Without common ground, Tong warned that arguments about the direction of the grid could go on indefinitely. Setting up common principles for a dialogue between utilities, customers, regulators, and third parties can build a more fruitful conversation.

“The principles are agnostic. They are not anti-utility or pro-DER. If we can agree on these principles, we can talk more constructively," Tong said.