The media has not been kind to the concentrated solar power (CSP) industry of late.

Not even a month ago, Greentech Media wondered aloud if the now-defunct Palen CSP project might be the last of its kind built in the U.S. And not long before that, the Christian Science Monitor asked if CSP had “missed its chance” to capture the industry from solar photovoltaics. Consulting firm Navigant told the world it thinks the CSP market is losing steam, the Wall Street Journal (among others) mocked it for “scorching” birds and the Motley Fool called it “already dead.”

But to many close to the CSP business, rumors of its demise have been greatly exaggerated. Analysts and industry insiders both acknowledge that the economic landscape in the short term is rough for new CSP projects. But, given time for cost reductions and the right regulatory environment, CSP may still have a robust role to play.

The looming end of the investment tax credit

One of the biggest questions about CSP’s future has to do with the federal investment tax credit (ITC).

The current ITC for solar provides a 30% credit for any residential or commercial project once in service, but the ITC is due to expire at the end of 2016. As it turns out, the “in service” part has proven to be a problem.

Under Section 45 of the tax code, certain renewables are allowed to take advantage of the ITC once construction begins—an exemption written into the 2013 ITC extension known as a “commence construction” requirement. Solar, however, is listed in Section 48 of the tax code, and cannot take advantage of the loophole. Instead, solar projects must be placed in service before investors can take advantage of the ITC.

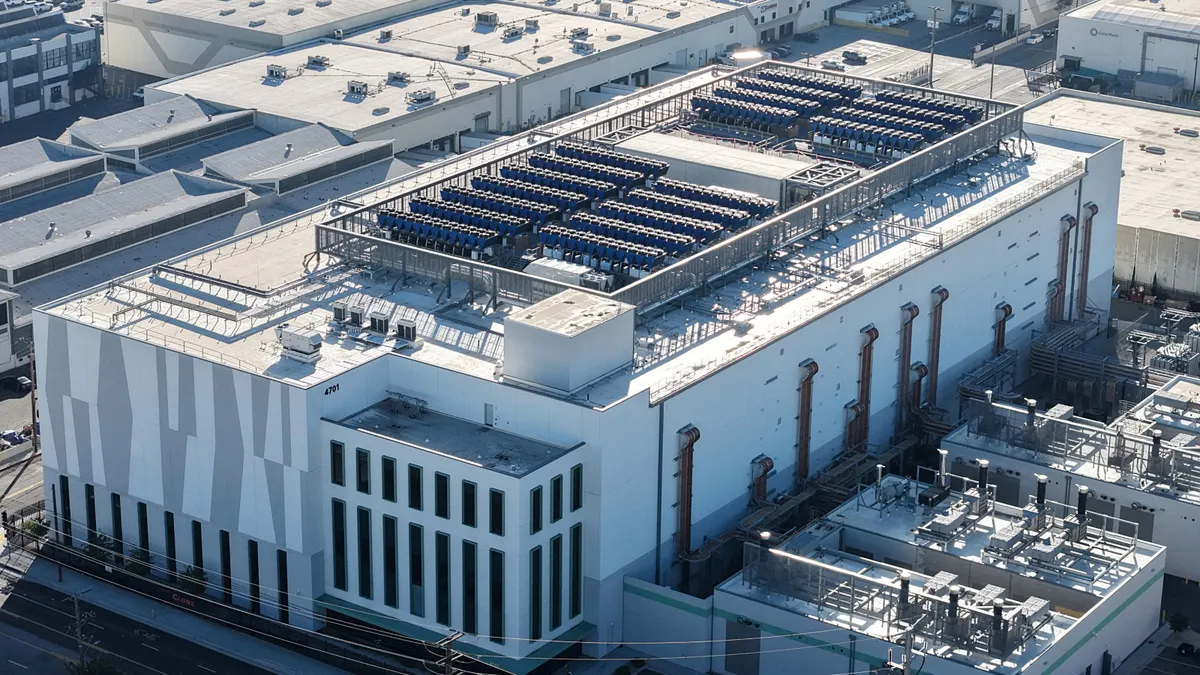

For CSP, that timeline spells trouble. The gigantic solar arrays, towers, and parabolic troughs used in CSP projects can take years to build, and even longer to get permitted and approved by local, state, and federal stakeholders. The developers of Ivanpah, the largest CSP plant in the world, for instance, first began applying for loan guarantees in 2006. The plant began operating earlier this year.

The lengthy timeline means it is practically impossible to get new CSP projects up and running in time to take advantage of the tax credit. And lenders demand months of cushion between the expected completion date and the expiration of the tax credit, squeezing the schedule even more.

“While the ITC expires at the end of the 2016—assuming there’s no extension—lenders require you to be placed in service at least 6 months prior to that,” Joe Desmond, senior vice president for marketing and governmental affairs at solar project developer BrightSource, told Utility Dive in an interview.

For the CSP industry, it’s as if the ITC has already expired, he said.

“If you’re a large power plant, no investor is going to lend money for a CSP project and say ‘As long as you’re operational by December 30, 2016 and everything goes perfect [we’ll approve a loan].’ No one is going to take that risk,” he said. “They’re going to back that off a few months, and from there you would back off construction time, and then you begin to see that the impact of the expired ITC is being felt today as opposed to another two years.”

That elongated timeline for construction and permitting explains why the CSP industry is committing much of its time and energy to addressing the discrepancy between “placed in service” and “commence construction” requirements. Private companies and the Solar Energy Industry Association (SEIA) have been pressuring Congress and the Obama administration to include Section 48 in the “commenced construction” requirement—if not extend the ITC outright.

“There was a Dear Colleague letter that 30-some senators signed, and lot of work that the industry has done to educate folks,” Desmond said. “But, it’s because these projects require multi-year development timelines and [expanding the 'commenced construction' requirement] gives you certainty and flexibility to move forward.”

“Arguably, when Congress wrote the tax credit, they intended it to be utilized for the entire term, not so no one could use it two years before it expired,” he added.

Of course, passing new tax legislation through Congress either before or after the midterms would be no small achievement. But even if their efforts stall, CSP proponents still see a bright future for the technology. Particularly when paired with energy storage, they say, CSP offers advantages that other resources do not.

The future of CSP: Hybridization and cost reductions

While the CSP industry may be going through a rough patch of tax uncertainty today, some analysts say there is a turnaround in the offing.

“I would say that further down the line there’s still ... opportunities for a revitalization of CSP’s role in the broader energy landscape, especially relative to PV,” Cory Honeyman, solar analyst with GTM Research, told Utility Dive in an interview.

Honeyman, like many in the CSP industry, stakes his hope on the technology's ability to store electricity efficiently, a feature other renewable resources conspicuously lack. Instead of relying on still-costly batteries, CSP plants can store water, oil, molten salt, or air that gets super-heated by the sun’s rays. When the grid reaches peak demand in the early evening and solar PV systems aren’t producing at maximum output, CSP systems can step in to fill the demand. The symbiotic relationship between CSP and PV is why casting the two as competitors in the market is like making an “apples to oranges comparison,” Honeyman said.

“I think down the road we will be talking about PV as being the primary daytime renewable whereas CSP represents a really attractive opportunity for providing power in the evening when it's paired with storage,” Honeyman said.

For Desmond, the advantages of CSP with storage go beyond providing reliability. The “solar steam” produced from CSP plants could be used as a low-carbon alternative in a variety of industries, mining processes and agricultural applications, he said. The steam can also be run through conventional power generators.

“There’s been a number of solicitations out in the last couple of months for augmenting solar steam into the steam cycle for a natural gas or a coal plant,” Desmond said. “That sort of hybridization remains a very good opportunity in light of the proposed EPA [greenhouse gas] rules.”

The economics of pairing CSP with storage is still at a nascent stage, Honeyman warned, but “at this point in time, the ancillary benefits of pairing CSP with storage is the beacon of hope for new projects.”

Fortunately for the CSP industry, the cost of constructing large scale CSP plants is likely to drop significantly in the next few years, Honeyman and Desmond agreed. While the red-hot PV market has driven down prices 80% since 2008, there’s still room for big savings with CSP.

“For CSP, the silver lining of the challenges to date is that there’s still a lot of opportunities for meaningful cost reductions on the hardware side,” Honeyman said.

Even better for CSP, peak periods will likely be pushed back into the late afternoon and evening in the coming years as the penetration of rooftop solar increases. This, Honeyman explained, will accentuate the value proposition for CSP with storage. But he was quick to add that there’s no set timetable for when CSP can begin to play a meaningful complementary role to PV and other distributed generation.

“That’s solely dependent on the ability of CSP to continue to manage these cost reductions,” he said.

The never-ending challenge of permitting

Costs may not be the most challenging problem for new CSP projects.

Siting and permitting new solar arrays has proven quite difficult for a number of ambitious projects, most recently the Palen Solar Power Project planned by BrightSource and Abengoa. After public outcry over bird deaths at other CSP installations like Ivanpah, as well as other permitting difficulties, the Palen developers scrapped the project.

“I think looking at the Palen project and its proceedings is sort of a microcosm of some of the challenges that any developer of CSP is facing,” Honeyman said. “There are a lot of challenges with siting and a lot of other early stage development milestones with respect to permitting and environmental compliance issues, and we saw that with Palen.”

While the site is still active and could be developed in the future, BrightSource and its development partners determined it was “in the best interest of all parties to bring forth a project that we felt would better meet the needs of the market and of consumers,” Desmond said.

But, despite the positive economic outlook for CSP projects in the future, permitting issues are highly localized and complex, Honeyman cautioned. The CSP industry, even as it manages its cost reductions, will continue to wrestle with the most effective way to move through permitting processes around the country. The industry's ability to quickly and efficiently get permitting may well prove as important as any other single factor in the development of CSP technology.

“That’s a challenge where the solutions, at least from my perspective, seem a little bit murky,” Honeyman said.