Sarah Steinberg is a director at national business association Advanced Energy United. Brad Cebulko is a senior manager at consulting practice Strategen.

In business, the only constant is disruption and change. We’ve seen this truth manifest across all industries, from telecommunications to retail to computing and manufacturing. The energy industry is no exception. Both gas and electric energy systems are becoming increasingly complex, with more dynamic supply and demand-side market forces instigating a profound evolution in how our power is sourced, priced and delivered. Change has come quicker to the electric side, but recently we have begun to see how the gas delivery system used to heat and cool homes and businesses is primed for change, and it should challenge the business-as-usual strategies currently used to regulate these essential services for ratepayers across the country.

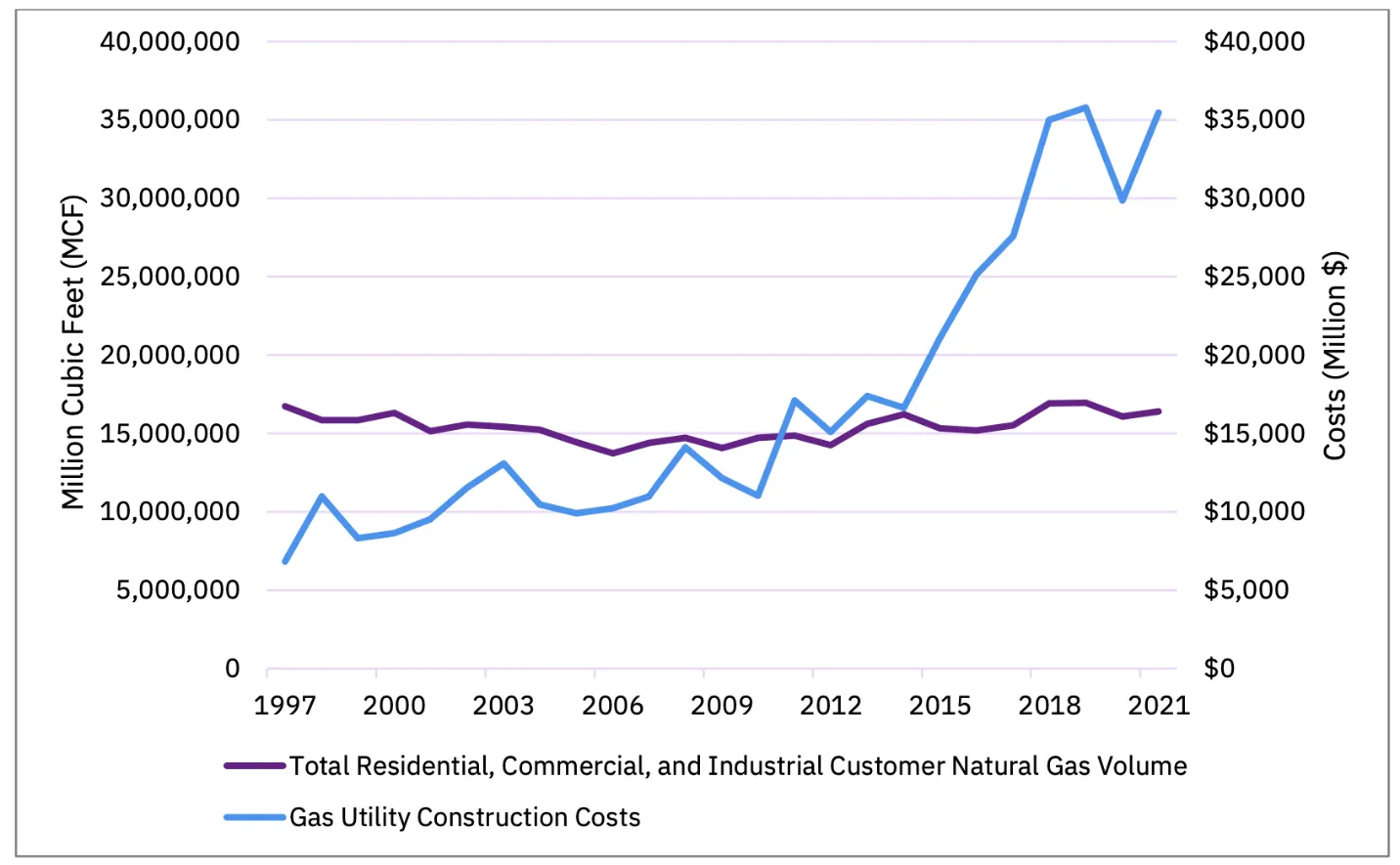

The rise of high-performing electric appliances in the marketplace — including, but not limited to, air and ground source heat pumps, mini-splits, heat pump water heaters, heat pump dryers and induction stoves — is threatening the gas utility monopoly over home heating and hot water. In fact, heat pump shipments have surpassed those of gas furnaces for two years running, all while new federal tax credits and rebate programs that lower the upfront cost of these clean technologies are just beginning to kick in. Gas prices remain volatile, and as shown in the figure below, pipeline infrastructure spending is accelerating far faster than demand is growing.

Moreover, many states have grown their ambitions to phase out fossil fuels, all necessitating further action to deploy non-polluting technologies. The risk to gas utilities, and the future use of their infrastructure, is obvious. Accelerating capital investments in long-lived gas pipelines combined with flat or declining load leads to rate increases. And given the growing penetration of high-efficiency electric appliances, the gas industry now may be overinvesting in infrastructure buildout when the demand for this service may have peaked, increasing the risk of stranded system assets and excessive costs passed to ratepayers.

Herein lies a fundamental question about the future: What long-lived energy infrastructure, with an operational life of more than 50 years, is right to build for our needs? Our needs today? Ten years from now? Thirty years from now?

In the electric utility sector, most states require utilities to submit regular “integrated resource plans,” that are subject to extensive modeling exercises to forecast customer demand over decades, estimate energy commodity and technology costs, assess the potential of various resource types, anticipate future policy changes, and more. Given these inputs, the utilities select a portfolio of resources — for example, solar and wind, geothermal, energy storage, transmission, energy efficiency and demand response — that together meet the needs of their forecasted customer base at the lowest reasonable cost, balancing near-term need with longer-term risk. Though it varies state by state — and some are better than others — most of these planning processes allow stakeholders to participate or intervene to understand, question, support or oppose the vision of the future put forth by the utility. After receiving a stamp of approval by regulators, utilities begin the process of procuring the resources and investments identified in the plan.

Such a transparent and public framework barely exists when it comes to gas distribution utilities, which are more often assessing resource and infrastructure needs in private. Afterwards, these companies use general rate cases and purchase gas adjustments to recover costs on those investments already made, or a budget within which they have the discretion to allocate among projects. Without a public, long-term planning process, state regulators and other parties have little ability to scrutinize a utility’s assumptions about the future, its forecasted costs and performance of various resources, and little insight into the long-term vision of the utility. It also means that regulators and stakeholders have no real idea of what a gas utility’s plan is if either gas sales or customer counts decline.

Under this regulatory paradigm, gas utilities are incentivized to continue making capital investments, as this is how the utility earns its return on equity for shareholders. Yet in this moment of technology, market and policy risk, it is not in the best interest of captive utility customers to let long-lived gas delivery infrastructure spending go unvetted, especially if that infrastructure may no longer be fully utilized in the near future.

Each state is likely to choose a different energy future for its residents, and regulators need to take advantage of the tools available to them. That’s why we believe that the time is now for states to create new gas utility planning processes akin to their electric utility counterparts.

Comprehensive, modern gas system planning has numerous benefits, including cost and risk mitigation, transparency, modeling of pathways that comply with state energy goals, and improved intra- and inter-utility coordination. Yet setting up, modernizing and iterating on regulatory processes can be challenging. It’s with this in mind that Advanced Energy United and Strategen Consulting crafted a “Regulator’s Blueprint for 21st Century Gas Utility Planning,” which explores the benefits of modern gas planning, details the process and analytical features that make a gas plan robust and reviews several existing gas planning processes in states such as Washington, Michigan, Colorado and New York, as well as the Canadian province of British Columbia.

Gas customers need reliable, affordable and safe service. Yet energy customers also deserve to know whether their utility is charging them the lowest possible cost for service, which means that the utility must have assessed all future risks, bill impacts and lower-cost alternatives to traditional pipeline service under regulatory and public scrutiny. Ultimately, it’s the gas utility customers who bear the risks of over- or under-investment, or of investment in the wrong resources. Utility regulators have a responsibility to understand and mitigate these risks.