UPDATE: October 13, 2021: FERC Chairman Richard Glick on Tuesday named Elin Katz as director of the commission’s Office of Public Participation.

Katz led the Connecticut Office of Consumer Counsel until 2019. The office advocates for consumers at the Connecticut Public Utilities Regulatory Authority and in court cases. Most recently, Katz was vice president for utilities at Tilson Technology Management. Katz starts her job at FERC in late November.

"This is a groundbreaking position at FERC that will assist the public and drive meaningful participation from a diverse range of stakeholders to help strengthen our decisions," Glick said.

June 30: Forty-three years ago, President Jimmy Carter signed the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) into law, in a move intended to wean the U.S. off traditional sources of power and strengthen energy security. But a lesser-known provision in the law escaped implementation until now.

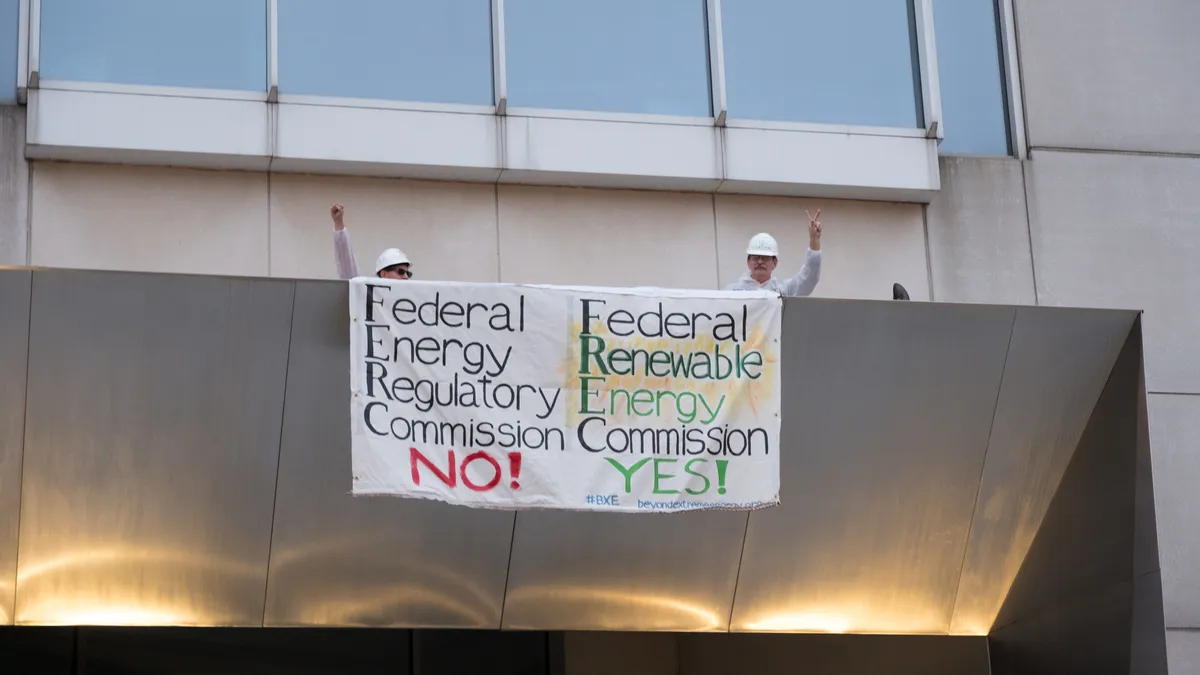

Last week, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission — pursuant to section 319 of the Federal Power Act (FPA), implemented under PURPA — established the Office of Public Participation (OPP), an office intended to make it easier for smaller organizations and individuals to participate in FERC proceedings.

The effort was led by Commissioner Allison Clements, and is the culmination of months of listening sessions and almost 250 comments from intervenors.

"As commissioners, we take votes on many important and pressing issues," said Clements. "That said, I'm sure this is one of the most important things that will happen during my tenure at the commission."

"There's no doubt there's an inequity" in who is able to engage in FERC proceedings, said FERC Chair Richard Glick. "And I think that's part of what this Office of Public Participation is intended to do, is to provide an opportunity — not just for those that with significant resources — but those that may not have similar resources to be able to get some insight into what we're doing, and hopefully have a say in the outcome."

Though the office was mandated by PURPA in 1978, the funding was removed from appropriations just a year later and never taken up again by FERC until this year, despite some advocates pushing for the independent agency, which became self-funded in 1986, to establish the office.

But in Congress' fiscal year 2021 consolidated appropriations act, a single paragraph on page 153 of the 217-page energy and water section directed FERC back to its 1978 mandate. The paragraph was the result of a nearly 20-year battle, led by Tyson Slocum, director of Public Citizen's energy program following his discovery of the provision after the California energy crisis in 2000/2001.

"This was an issue that I raised with every FERC chairperson, ... Democrat and Republican," said Slocum.

"And we just never were able to get that done," he added. "Nobody was willing to do it."

Four decades in the making

In a 1977 analysis of the National Energy Act, Joseph Swidler, representing Commonwealth Edison, called bureaucratic delays on rate and certification proceedings "[o]ne of the greatest burdens on the electric utilities in their efforts to plan for the future." He cautioned that the intervention of "special interest groups … purporting to speak for a variety of environmental and consumer interests" has made those proceedings even more tedious, and argued that to fund these public participation efforts was to fund unnecessary delays to rate proceedings.

"In effect, the funding of intervenors represents frustration through the use of federal funds of the purposes for which regulatory authorities are established, which is to dispose of proceedings as promptly as possible, consistent with a full and fair hearing," he wrote in his analysis presented to Congress.

His testimony is the only evidence in front of Congress on record Public Citizen found that argues against establishing the Office of Public Participation. It's unclear whether this testimony influenced Congress, but in the Congressional appropriations for fiscal year 1979 — seven years before FERC became self-funded — a single line took away FERC's authority to implement the OPP that year: "None of the funds appropriated for Department of Energy activities by this Act shall be used to pay expenses of, or otherwise compensate, parties intervening in regulatory or adjudicatory proceedings funded in this Act."

It wasn't until more than 20 years later, in the midst of fallout from the Enron scandal and efforts by President George W. Bush's administration to pass sweeping energy policy, that the provision bubbled up again.

As Congress was considering broad reforms to U.S. energy policy, the office of then-Rep. Ed Markey, D-Mass., was looking for ways to increase consumer protections, and in digging through statutes found the 319 provision that had yet to be implemented.

"Nobody had really a good explanation as to why that happened," said Markey's senior adviser at the time Jeff Duncan. "But the reality is basically it passed towards the end of the Carter administration, and the Reagan administration had zero interest in it."

Duncan brought the provision to Slocum in the early 2000s, but the Bush administration "had zero interest in it" either, said Duncan. "And the thing just got shelved basically."

But the provision got Slocum's attention, and he lobbied FERC chair after chair, eventually gathering a coalition behind him to formally petition the commission in 2016 to establish the office. After FERC failed to respond, in early 2020, Slocum began to engage groups in bringing forward a lawsuit against the commission.

Then, the pandemic hit. Public Citizen was attempting to prevent rulemakings from happening in the midst of the economic shutdown, and realized they couldn't ask the administration to do that and then sue them for not moving forward on their petition.

So Slocum instead turned to Congress, and managed through the House Energy and Commerce Committee to stick the OPP language into appropriations for 2021 before the omnibus spending bill passed. Ultimately, the addition, when set next to everything else included in the bill, didn't raise any concerns on either side of the aisle, and it passed.

"It was a situation where there were a lot of presents under the Christmas tree," said Slocum. "And this one ended up making it through until Christmas morning."

The provision directed FERC to send Congress a report on establishing the OPP by June 25. FERC released its report June 24.

Adam Benshoff, vice president for regulatory affairs at Edison Electric Institute, which represents investor-owned utilities, said in an emailed statement "the office will play an important role in demystifying the process while providing interested stakeholders with the information they need to ensure their voices are heard."

Tony Clark — a former FERC chair who is now a senior adviser at law firm Wilkinson, Barker, Knauer, LLP, and regularly works with utilities — said the office could be helpful to many parties "if the OPP can help facilitate a sharing of information between the commission, public and industry."

"FERC depends on a good record to make decisions; and FERC processes, like those of so many regulatory agencies, are complex, especially to most members of the public who don’t interact with them much, if at all," he said in an email, adding that "[t]he only caution I've expressed is I wouldn’t want it to become just one more cog in the bureaucracy that adds red tape to a regulatory [process] that isn't in need of any more complexity."

Glick cautioned the office is still in its early stages, and urged stakeholders to be patient as its rolled out. "This isn't going to change overnight," he said.

'The commission has a long way to go'

Ultimately, the Office of Public Participation was intended to ensure ratepayer voices were given an equal opportunity to be heard. In its petition to FERC in 2016, Public Citizen quoted Sen. Howard Metzenbaum, D-Ohio, speaking on the Senate floor in 1978 about the provision.

"For the first time, the Congress has assured the electric consumers of this country that their voice will be heard. ... This is a great victory for the consumer, who will finally be able to compete on an even footing with the utility industry of this Nation," Metzenbaum said at the time.

Throughout FERC's six listening sessions and a 63-day comment period on its proposal to establish the OPP, the commission received comments from an array of stakeholders including landowners, community organizers, consumer advocates and Tribal governments, many impacted by FERC decisions and wanting to have a louder voice in the process. Glick and Clements said the meetings and comments showed them how complex, and sometimes inaccessible, FERC can be to the average person.

"The commission has a long way to go," said Clements. "I was surprised by how much it meant to individuals to have the chance to speak about their experience with the commission. And I think that establishing the Office Public Participation is a meaningful step towards ensuring that the voices of individuals and communities who are impacted by the Commission's decisions are not only heard, but are weighed in our decision making [and] in our votes."

"There's a strong feeling out there that our orders or actions — whether it be on the natural gas pipeline siting side, hydro electric licensing, electric rate cases, transmission and so on — they all directly impact these folks and people ... want to be part of the process. So that's really what I learned," said Glick.

OPP will be developed by FERC over the next four years, and in its first year the commission will hire a director, deputy director and administrative staff member. In 2022, the office will help the commission develop a rulemaking to establish intervenor funding, one of the most essential ways to ensure grassroots movements or smaller organizations can engage on a level playing field with utilities and other groups that have deeper pockets, according to Slocum. The funding will provide financial support to public interest groups to cover the costs of intervening before the commission.

"FERC can only address issues raised in the proceeding, and to raise issues in a proceeding, you have to have resources," said Slocum, adding that Glick and Clements deserve credit for ensuring that the funding mechanism is put into place as quickly as possible. Public Citizen also wants to see the commission go a step further to ensure true grassroots movements can have a seat at the table: It proposed in its comments filed with FERC on the proceeding that the commission establish a public interest attorney referral program. Such a program would find qualified attorneys and pay them through the intervenor funding to represent groups that aren't able to hire an attorney.

"All this does is level the playing field," said Slocum. "We're asking FERC to give us what they've given utilities from day one."

Glick said more specifics will be rolled out once a director is hired, and the rulemaking process under the advisement of that director will determine exactly how intervenor funding is allocated. He and the commission are weighing all comments, and stakeholders discussed different potential models in the workshop FERC hosted earlier this year, including exploring how different state agencies have set up their own intervenor funding models.

"We're weighing all of these factors, but in reality, we're going to wait until we get a director, and he or she will make some recommendations to us," Glick said.

This post has been updated with comment from EEI.