Shahid Mahdi is a product manager at EnerKnol.

Gas giant Colonial Pipeline falling to the stealthy sabre of DarkSide, a notorious Russian ransomware group, was a seminal moment in the annals of cybersecurity. Prior to this, cyber influence was either mythologized as being a capability for states to accomplish their geopolitical or informational goals, like Stuxnet, or it had been relegated to being a peripheral topic of pop culture, with mass media promulgating images of people frantically hammering away at keyboards and hooded figures lurking in dark corners.

But in May of 2021, Colonial Pipeline, acting out of panic in the face of an invisible adversary they had not faced before, shut down, and in doing so stymied millions across several critical infrastructure sectors. Cyberattacks and disruptions have embedded themselves into the fabric of this decade's life as nations all jostle to spread their influence within a new, formidable plane beyond land, air and sea, and the automotive industry is in for a not-so-joyful ride.

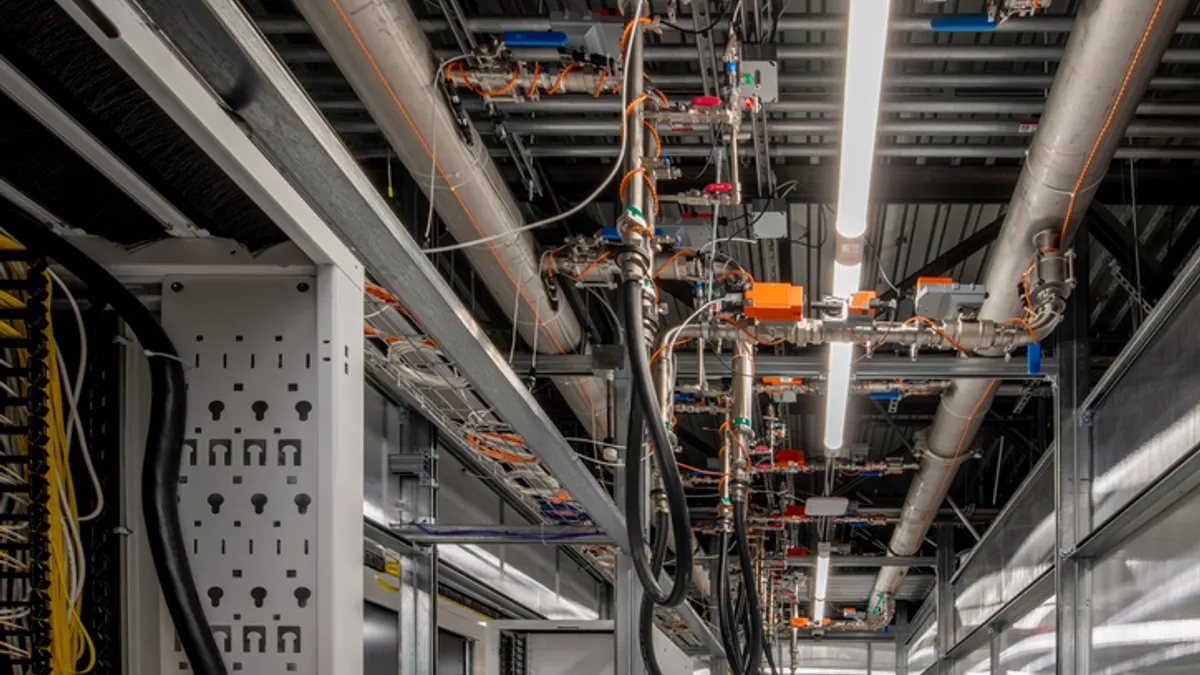

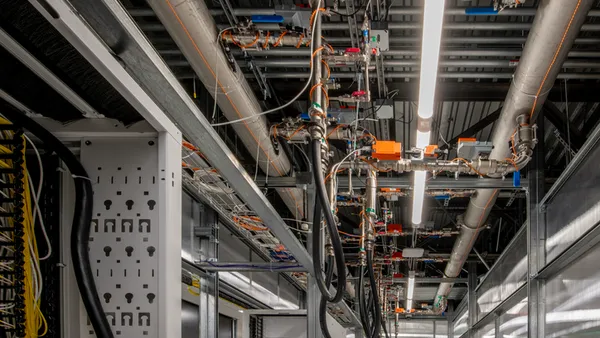

The digitization of vehicles, notably electric ones and commensurate charging infrastructure, presents new challenges and risks in the cyber domain. The average electric vehicle has about 3,000 chips, more than double the number in non-electric vehicles, rendering it that much more prone to cyber risks from these chips' software. Charging stations — 500,000 of which will be installed with funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act — will be relied upon to safely store sensitive, personal data including payment information and insight into drivers' routines.

Yet, all of the above exists on IoT networks as part of a collective surge towards a "smart device" future. Our fridges, phones, audio speakers, thermostats and fitness trackers exist on highly sophisticated, shared networks, and now our cars do too. In one respect, the notion of everything slotting into the same software ecosystem, e.g. Apple synchronizing your iPhone's contacts on CarPlay, is massively convenient. Looking up that upstate getaway route on your iPad? Your car's GPS is already suggesting the fastest path as you turn the keys.

However, we must come to terms with the unsavory truth: anything that is “smart” digitally is also entirely hackable. Vehicles from an array of manufacturers now experience software updates as routinely as your smartphone does. Said updates account for dozens of vulnerabilities that a car software’s native engineers are paid to discover before an adversary can exploit them.

The future is now, and we’re getting a peek into the multifaceted threats that "smarter" technologies, notably cars, are vulnerable to. The NCC Group, a notable cybersecurity firm, showcased how easy it is to unlock Tesla car doors by interfering with their Bluetooth capabilities. Pen Test Partners were able to identify a "backdoor" in charging stations that can permit the perpetrator access to the smart-device network in homes.

Public charging infrastructure, which is embedded into outdated grid systems, has already cemented itself as a ripe target for compromise. As is the case innately with cyber affronts, the enemy is invisible and clandestine — Deloitte Canada reports that 84% of cybersecurity-concerning EV incidents derived from remote attacks; with 50% of said malware deployed in the past two years.

As buyers switch from gasoline-powered vehicles to electric ones, they need to be cognizant of the new frontier of cyber threats. Reputable cybersecurity experts including Roy Fridman, CEO of C2A, have been vociferous about how security needs to start at the automaker level. But beyond that, regulatory standards should be set in place.

Some promising steps, and more to be done

Across the past year, some promising steps have been taken, notably in the form of ISO/SAE 21434:2021, which outlines software testing requirements for vehicle manufacturers, as well as the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's proposals pertinent to said software. State and federal legislatures, in the wake of the Colonial Pipeline incident, have also begun to push cyber security preparedness bills through their chambers: The U.S. House of Representatives introduced an abundance of cybersecurity training bills in November 2022, along with the Small Business Cybersecurity Enhancement Act and the U.S. Senate’s Intragovernmental Cybersecurity Sharing Act.

But automakers, car owners, grid operators, governmental entities, and especially car owners need to be in tandem about holistic cybersecurity protocols. Non-state cyber threats that are fostered and tolerated by the governments of Russia and China will only increase in power as geopolitical bellicosity rises.

In the same manner that the North American Electric Reliability Corporation erected the Reliability and Technical Committee to uphold summer and winter readiness standards in the wake of Winter Storm Uri battering Texas in 2021, the Biden Administration ought to create a specialized, public-private partnership forum wherein manufacturers, highway administrators, cybersecurity experts, and state representatives can begin to foster a dialogue that urgently needs to start.

By 2030, it is projected that over 60% of all vehicle sales globally will be electric. This permeates into industries and functionalities beyond the common civilian motorist: freight transportation, law enforcement, ambulances and emergency response team vehicles; even gig-economy worker transportation methods. If action is not taken to uniformly protect electric vehicles and charging infrastructure from cyber threats, the mobile exoskeleton of the U.S. could be targeted.

Smart technologies have dramatically convenienced our lives, and the environmental ramifications of en masse fleet electrification is a firm step in the right direction. But in cars getting “smarter” as they get more digitized, we must also ask if they are getting safer