Dive Brief:

-

The Environmental Protection Agency's top air regulator said Friday he is still determining whether climate change is a "crisis," but said his agency will continue its rollback of carbon regulations proposed by the Obama administration as he studies the issue.

-

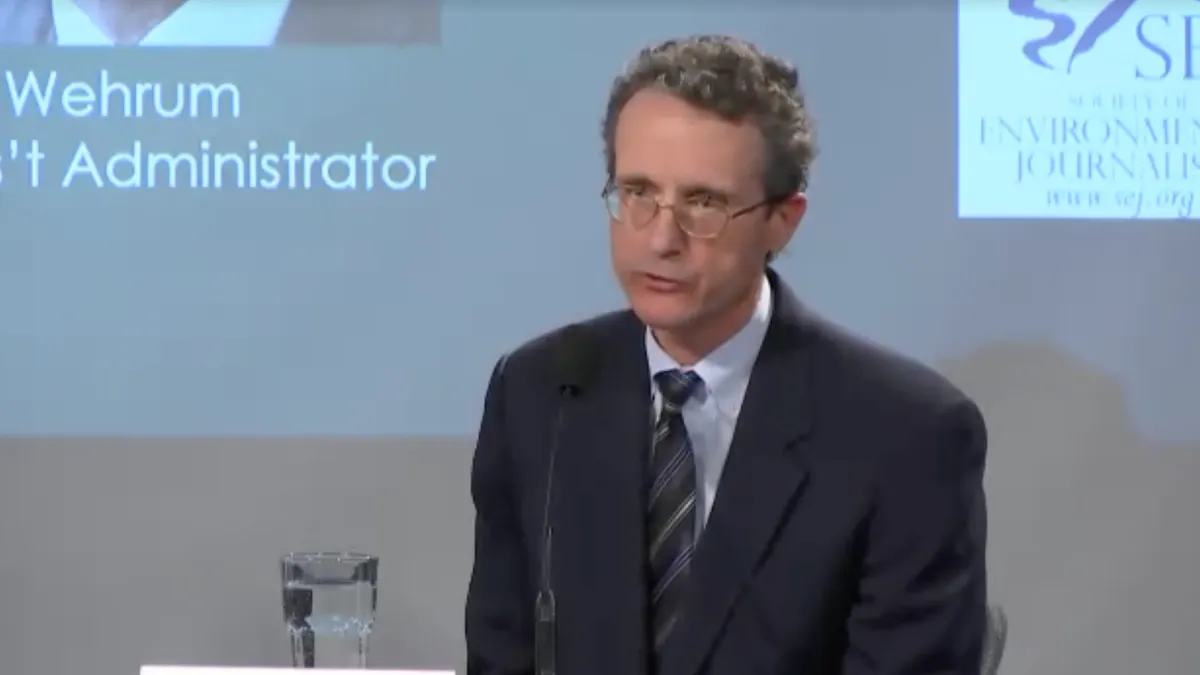

EPA Assistant Administrator Bill Wehrum said he is "trying to figure that out" when asked about the severity of climate change, but argued his agency's proposed Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule would cut carbon emissions to nearly the same level as Obama-era rules, despite being less stringent.

-

Wehrum also addressed the EPA's proposed changes to the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS), saying they would not cause power plants to turn off pollution control technologies, but could set a new precedent for how EPA writes regulations.

Dive Insight:

Wehrum's comments Friday afternoon at the Wilson Center are the latest from a Trump administration official to cast doubt on the scientific consensus around climate change and the severity of its threat to the U.S.

"There's a mountain of science related to climate change and I've only scaled foothills of it," he said, adding that "everybody is still exploring the science behind climate change."

In November, the EPA and 12 other federal agencies released a report warning that by the end of the century, annual climate change damages on U.S. industries could reach the hundreds of billions of dollars — more than the economic output of many states.

Wehrum said he had read the report summary and some key chapters, but remains unsure of the severity of the threat.

"I could spend all my available time and still not understand all there is to understand" on climate, Wehrum told the audience during a live interview. "I'm going to keep working at it, but in the meantime we're going to keep working on the rules, because our time is limited."

Chief among those rules is the agency's proposed ACE rule, which would set efficiency standards for coal generators and loosen permitting requirements for plant upgrades.

The EPA's analysis of the rule concluded that it would cause 1,400 more premature deaths than the Obama administration's Clean Power Plan (CPP), a more sweeping carbon regulation that was put on hold by the Supreme Court in 2015.

Wehrum, however, said that comparison was "taken out of context," because the CPP was not put into effect. EPA abandoned its legal defense of the rule after President Trump took office.

"The real comparison is how does ACE stack up against the world as it really is right now," he said. "Against that, ACE makes real progress in conjunction with amazing American ingenuity."

EPA estimates that ACE will reduce emissions 34% from 2005 levels by 2030, but a number of energy analysts warn it could actually raise emissions by allowing more efficient coal plants to run more often. An academic study released this month argued that when this "rebound effect" is taken into account, projected emissions reductions from ACE are much lower.

Wehrum pushed back on that argument, saying the agency had modeled the "rebound effect" in its proposed rule.

"I believe that we did and I'm being careful when I say that because a lot of analysis went into the proposed ACE rule and part of that came from the IPM rule, the integrated planning model rule," he said. "It's a very sophisticated rule that attempts to model how the power sector across the country will respond to regulations like this."

That model "predicts which facilities are going to operate and the level at which they will operate," he added, "so I believe our analytical measures take into account the relative load shifting from plant to plant depending on the effects of regulations that we propose to impose."

Wehrum and an EPA spokesperson did not respond to multiple inquiries on whether the agency is considering building a "safeguard" provision into the ACE rule to ensure emissions do not increase.

Altering MATS

Wehrum also addressed the EPA's decision to reconsider the underlying rationale for MATS, Obama-era rules on mercury and other toxic air pollutants from coal plants.

EPA in December moved to rescind its initial finding that the rule was "appropriate and necessary," sparking concern in the power sector that the agency could rescind the rule — one with which utilities have already complied.

Wehrum, however, reiterated the message that his boss, EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler, delivered to a Senate committee earlier this month: the agency will not attempt to roll back the mercury rules.

Instead, Wehrum said EPA intends to narrow its interpretation of whether a regulation is necessary after the Supreme Court invalidated the EPA's original finding in 2015.

"The Supreme Court in the Michigan case remanded the appropriate and necessary finding back to EPA and said we had done it wrong and we made a big mistake, and the big mistake we made was not to consider cost in deciding if it's appropriate and necessary to regulate power plants," he said.

The Obama-era EPA swiftly rewrote its underlying justification for the rule, but Wehrum said he believes that interpretation was "in error" because it accounted not only for the benefits of reducing hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) — the emissions target by MATS — but also the benefits of cutting particulate pollutants, which are covered by a separate section of the Clean Air Act.

Clean air advocates say narrowing the EPA's interpretation in this case could alter agency rulemaking in the future. Wehrum said that is part of the motivation behind the change, but "in a more targeted way" than critics argue.

"What we say in the proposed rule is that's the wrong way to think about it," he said. "Section 112 [of the Clean Air Act] is about regulating HAPs and if the threshold question is about whether it's appropriate and necessary to regulate HAPs, then we should look at HAPs and we shouldn't look at criteria pollutants."