New public and private funding and expected strong federal power plant emissions reduction standards have accelerated electricity sector investments in carbon capture, utilization and storage,’ or CCUS, projects but some worry it is good money thrown after bad.

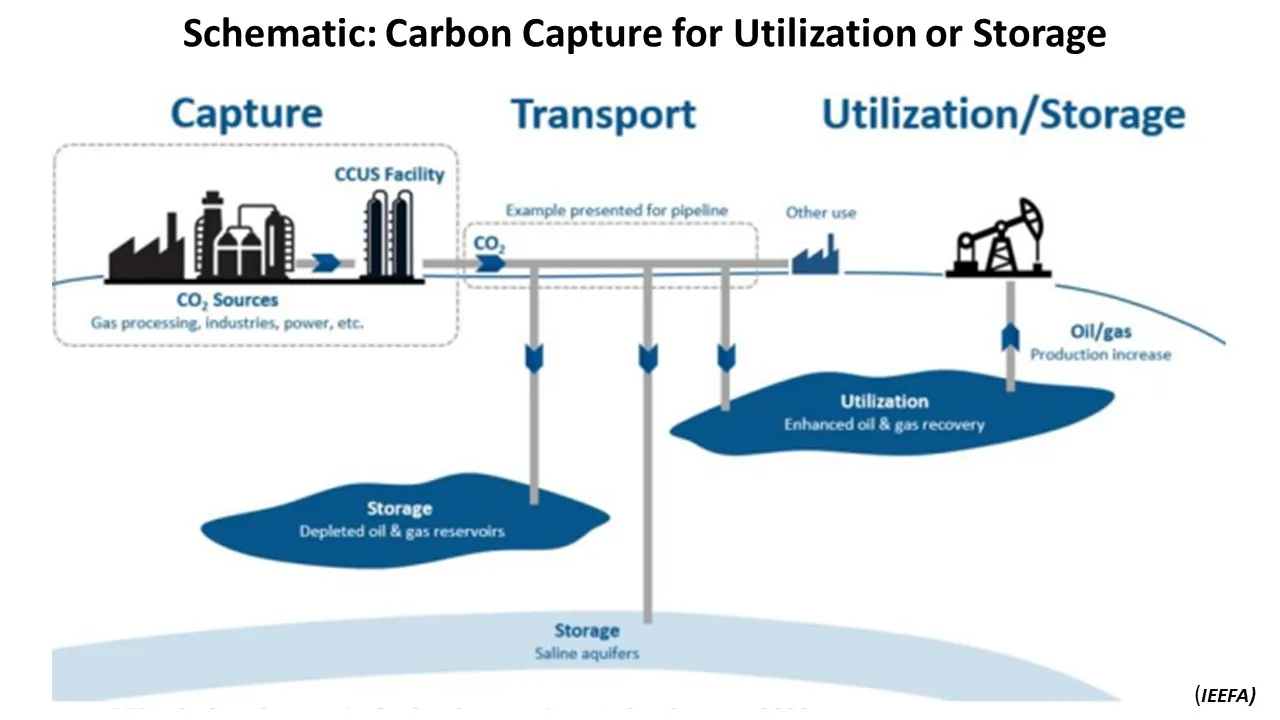

CCUS separates carbon from a fossil fuel-burning power plant’s exhaust for geologic storage or for use in industrial and other applications, according to the Department of Energy. Fossil fuel industry giants like Calpine and Chevron are looking to take advantage of new federal tax credits and grant funding for CCUS to manage potentially high costs in meeting power plant performance requirements, including new rules, expected from EPA soon, on reducing greenhouse gas emissions from existing power plants.

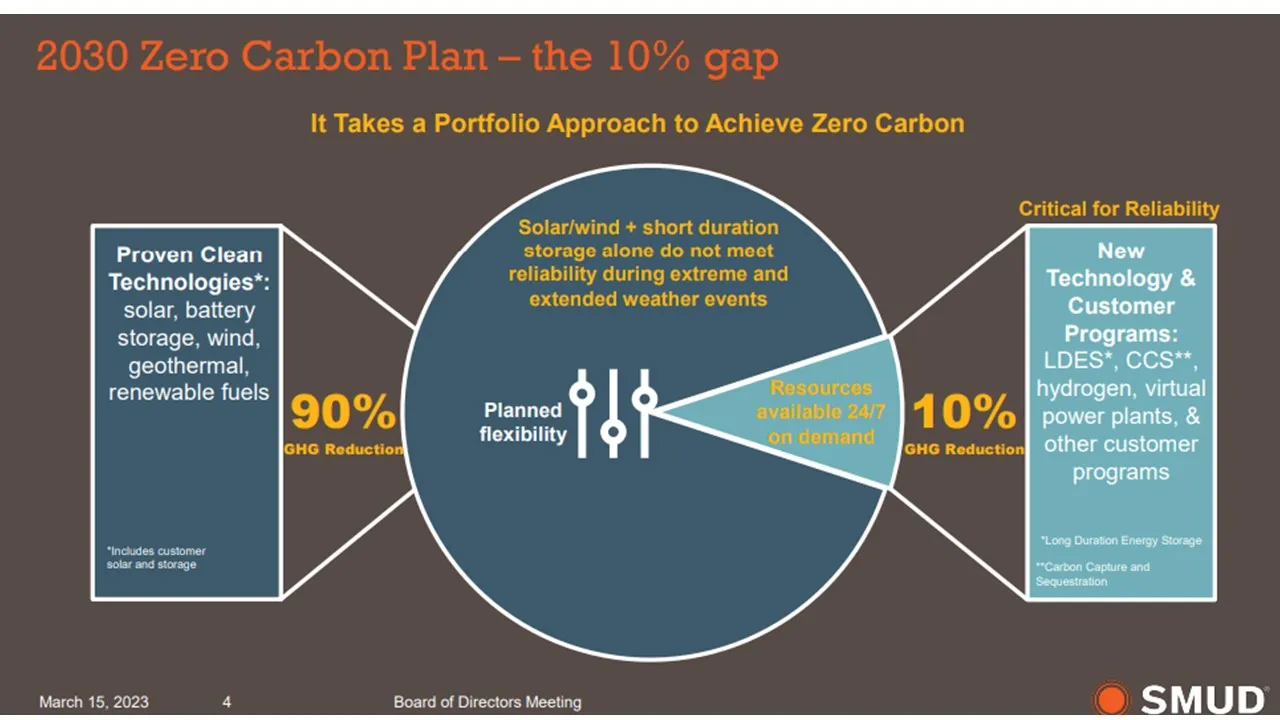

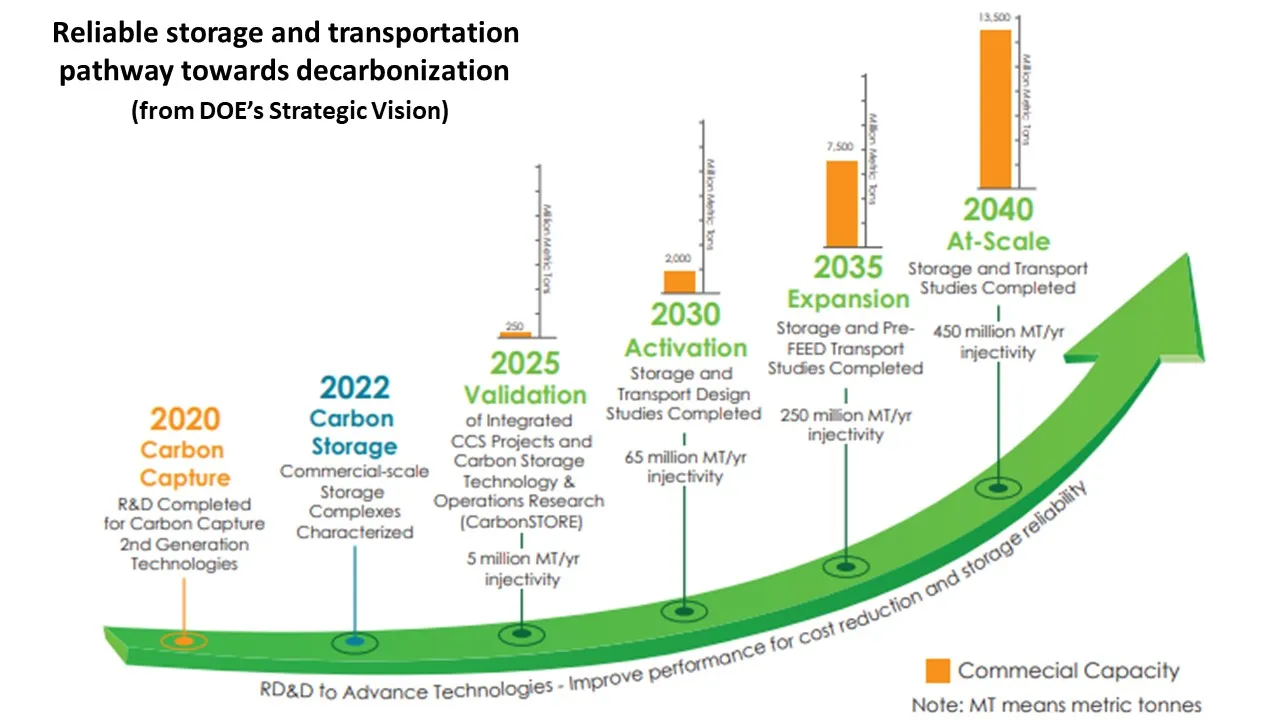

Power companies have “ambitious plans” to add CCUS to power plants, estimated to cause 25% of U.S. CO2 emissions, and the power sector “needs CCUS in its toolkit,” said DOE Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management Assistant Secretary Brad Crabtree. Successful pilots and demonstrations “will add to investor confidence and lead to more deployment” to provide dispatchable clean energy for power system reliability after 2030,| he added.

But environmentalists and others insist potentially cost-prohibitive CCUS infrastructure must still prove itself effective under rigorous and transparent federal oversight.

“The vast majority of long-term U.S. power sector needs can be met without fossil generation and there are better options being deployed and in development,” Sierra Club Senior Advisor, Strategic Research and Development, Jeremy Fisher said. CCUS “may be needed, but without better guardrails, power sector abuses of federal funding could lead to increased emissions and stranded fossil assets,” he added.

New DOE CCUS project grants, an increased $85 per metric ton, or tonne, federal 45Q tax credit, and the forthcoming EPA power plant carbon rules, will do for CCUS what similar policies did for renewables, advocates and opponents agreed. But controversial past CCUS performance and tax credit abuses must be avoided with transparent reporting requirements for CO2 capture, opponents added.

New funding, new life

Federal spending authorized by 2021’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the 45Q tax credit increase in 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act will make 2023 “a milestone year” for CCUS, moving it “from niche concept to mainstream investment,” and increase global CCUS capacity more than “sevenfold” by 2033, according to a March 2023 report by consultant Wood Mackenzie.

Tax credit support is a key reason many companies are investing in CCUS, Bloomberg News reported in January. Energy companies, like Competitive Power Ventures and Calpine, frankly acknowledged policy support as a key driver in recent CCUS proposal announcements.

The new public and private investment will allow power plants with CCUS to have a small positive or at least no more than a small negative financial return, said Clean Air Task Force Technology and Markets Director John Thompson. That may make CCUS a more cost-effective way to meet expected stricter pollution and emissions standards, he added.

DOE’s recent $2.5 billion offering for CCUS pilot and demonstration projects may be “an important opportunity for CCUS developers,” said Pamela T. Wu, a partner at the law firm Morgan Lewis. “It will identify which technologies are reaching implementation readiness levels to complement the continuing rapid deployment of renewables,” she added.

CCUS advocates agreed.

The point of CCUS support

“The point of the new federal investments is to support enough deployment to firmly establish the technology” and contradict some of the “misunderstandings” about past CCUS demonstrations, DOE’s Crabtree said.

Public debate consistently associates CCUS with enhanced oil recovery, which injects captured CO2 into aging oil wells to increase production, and “that is a misrepresentation,” Crabtree said. Congress set the enhanced oil recovery tax credit “at only $60 per tonne because producing oil earns revenue and because enhanced oil recovery limits the net climate benefit of CCUS,” he said.

CCUS opponents also argue the 2009 congressionally authorized grants for commercial-scale CCUS demonstrations at Boundary Dam, Petra Nova, and other coal plants underperformed, he added. But that should not stop DOE’s new efforts because “federal grants and tax credits supported solar and wind when early large-scale projects were expensive and performed hesitantly, and carbon capture is no different,” Crabtree said.

The new federal supports can make CCUS-equipped natural gas power plants valuable compliments to renewables and batteries in the U.S., added Carbon Capture Coalition Executive Director Jessie Stolark. And successful CCUS demonstrations at coal plants can allow U.S. technology “to help address Asia-Pacific region emissions where coal is still being used,” she added.

The history of past DOE-funded CCUS demonstrations, as detailed in the December 2021 Government Accountability Office report, “shows how to improve management and oversight,” Stolark wrote in January 2022. And the new federal tax credits and grants for power plant CCUS “go a long way toward providing federal policy parity” with clean energies, which was the “major barrier” to previous success, she added.

“The policy support for those big, complex, capital-intensive pioneer projects” was inadequate, Stolark said. “This time DOE made sure policy signals like the 45Q tax credit were in place before funding new demonstrations.”

And “proof” that CCUS is now “a cost-effective technology for reducing emissions” is the Clean Air Task Force - documented 160-plus project announcements since the 45Q credit was increased, she added.

But some environmentalists and economists said their data proves the opposite.

Performance and underperformance

Pioneer power plant demonstrations, like NRG Energy’s Petra Nova and SaskPower’s Boundary Dam, left many doubts about CCUS performance, according to Sierra Club, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, or IEEFA, and others.

The increased energy needed to run the Boundary Dam coal plant CCUS retrofit, for example, reduced its output from 160 MW to 110 MW, “a 31% parasitic load,” said independent analyst Brendan Pierpont, a former Climate Policy Institute analyst. A 2021 analysis found the result was underperformance that reduced the system’s design for 90% CO2 capture to 65%, he added.

Data submitted to DOE on Enchant Energy’s proposed San Juan Generating Station coal plant CCUS retrofit estimated its pre-CCUS output of 847 MW will drop to 482 MW, “an over 40% parasitic load,” Pierpont said. That would lead to significant underperformance in capturing emissions because “40% of the fuel burned and 40% of the emissions would be just to power the CCUS,” he added.

Calpine’s commitments to the Sacramento Municipal Utility District, or SMUD, on the CCUS opportunity in retrofitting the utility’s 578 MW Sutter Energy Center natural power plant raised several performance concerns from the utility’s consumer advocacy group.

The plant can offer “much-needed“ system reliability by adding dispatchable low emissions generation as SMUD advances its high variable renewables, zero carbon by 2030 plan, but data to assess “the risk and liability” is needed, SMUD Rate Advisor Rick Codina wrote for SMUDWatch. The utility needs to answer questions about CO2 capture rates, about how to avoid potential long-term dependence on fossil fuel generation, and about how it will deal with natural gas price volatility and other uncertain operational costs, he added.

These examples reflect broader concerns of some with the economic viability of CCUS.

The levelized cost of electricity for power plants with CCUS is “at least 1.5 times to 2 times above current alternatives, which include renewable energy plus storage,” according to a March 30 IEEFA paper.

The only improvement in CCUS economics from past demonstrations “is that the federal tax credits and DOE grants are shifting part of the cost and risk to taxpayers,” said IEEFA Director of Resource Planning Analysis David Schlissel. DOE’s recent demonstration and pilot grants are “a good approach” because “they limit spending of taxpayer dollars until it is clear what works and what will be needed in 2040,” he added.

The 45Q tax credits help CCUS, but “the IRA’s overall provisions still make retiring coal plants and building renewables the economic choice,” agreed Rhodium Group Energy and Climate Practice Associate Director Ben King. Some CCUS will be built, and “if the DOE pilot and demonstration projects’ performance drives down cost and builds market confidence, there could be more,” he said.

Independent analyst Pierpont is more skeptical. The tax credit and DOE grants “could overcome some technical and operational issues,” but the performance questions “are fundamental to CCUS’s long-term financial viability,” and if politics undermine federal supports, CCUS investments “could become stranded assets with many years of amortized costs embedded in customer rates,” he added.

Clean firm dispatchable power will have higher value after 2030, but CCUS will have competition from other clean energy technologies, and CCUS may not be clean if better oversight does not produce accountability, Pierpont said.

The need for oversight and accountability for CCUS pilots and demonstrations is not in dispute, but how to get it is, Pierpoint and Sierra Club’s Fisher said.

Transparency and guardrails

CCUS advocates said oversight is built into the new federal initiatives.

“If performance is not verified, plant owners do not receive the $85 per tonne [tax credit] that makes projects financially viable,” said the Clean Air Task Force’s Thompson. “That is an incentive to plant owners to achieve the highest possible levels of performance,” he added.

But the tax code’s section 45Q “does not specify when and how taxpayers must demonstrate” they have met the 75% of baseline emissions “capture design capacity requirement,” Calpine’s December 2022 Treasury Department filing said. IRS guidance is needed “that furthers Congressional purposes,” it added.

Transparency is vital because the 45Q credit, which “should be an incentive to maximize CO2 capture,” can be used by developers instead “to maximize their return” without fulfilling the congressional intent to maximize emissions reductions, Sierra Club’s Fisher said. “That can be prevented by strong guardrails on the tax credit’s use and transparent data on captured and stored CO2,” he said.

Some fossil fuel plants currently do not run more than 50% of the time because they cannot compete in energy markets with low-cost renewables, Fisher said. As detailed in Sierra Club’s December 2022 Treasury filing, a small CCUS retrofit may meet the IRS’s 75% minimum capture requirement of those historically small baselines while reducing a retrofit’s capital cost, he added.

Revenue from the $85 per tonne tax credit would then make those plants’ production more cost-effective than not operating, Fisher said. But 75% of their 50% baselines means only 38% of emissions would be captured, uncaptured emissions would increase, and plant owners would earn 45Q revenue while minimizing capital costs for CCUS infrastructure, he concluded.

Treasury can address this by requiring “a rigorous recalculation of a plant’s baseline for any changes, including CCUS retrofits, to ensure they maximize carbon captured,” Fisher said. It should also require “transparently verified reporting of emissions captured throughout the CO2 chain, at the point of combustion, in the tower, and in transport and sequestration,” he added.

That will require due diligence by the IRS to protect taxpayers against unjustified claims for 45Q credits, he said. An April 2020 Treasury Department report showed that due diligence is necessary because 87% of 45Q tax credit claims between 2010 and 2019, totaling almost $894 million, did not meet EPA requirements for monitoring, verification and reporting, he said.

Transparency has been limited by IRS confidentiality requirements, but new efforts by the EPA may improve that, DOE’s Crabtree said.

“EPA can require better and more transparent auditing and recordkeeping,” Fisher said. “Transparency and accountability” are vital to “the integrity of the 45Q tax credit,” the Carbon Capture Coalition’s April 2023 Federal Policy Blueprint agreed. Calpine’s Treasury filing called for reassessing a plant’s baseline following any “major modification.”

Power plant 45Q tax credit claims must include “an EPA-approved Monitoring, Reporting and Verification plan” and make data publicly available, according to agency spokesperson Shayla R. Powell. But current reporting rules do not require data on CO2 beyond the power plant, and an EPA rulemaking begun in June 2022 focuses on CO2 for enhanced oil recovery and in industry, but not at power plants.

For power plants, EPA must provide “rigorous accounting” and enforcement “from the point of capture to the point of permanent storage,” an April 2023 Natural Resources Defense Council brief responded, echoing Fisher.

With strong federal guardrails and oversight, CCUS could prove itself and find a role, some advocates and opponents said.

“The U.S. is spending a lot more on wind and solar subsidies” than for CCUS, said Rhodium’s King. And “the tax credit’s $85 per tonne is less than the EPA’s proposed $190 per tonne social cost of carbon, which means that with the right oversight and transparency, it may still prove to be an economic way to reduce emissions,” he added.