Editor's Note: This article is part of a series on the key issues driving the utility sector today. All stories in this series can be found here.

Who decides which power plants we build?

It's a question as old as the electric utility industry and one that defines how the sector serves its customers. It's also at the center of high-stakes policy debates across the United States today.

In many states, deregulation of power generation was supposed to answer that question with one thing — the market. Instead of utility boards and state commissions deciding what to build, forces of supply and demand for electricity would dictate which plants would be sited and which would retire.

That idea was the driving force behind the advent of wholesale power markets that serve about two-thirds of the U.S. population. But increasingly, states are dissatisfied with the outcomes of these markets and are enacting subsidies and mandates to help determine the generation mix within their borders. Renewable energy mandates and nuclear plant subsidies are prime examples.

"The nuclear subsidies I think are really what brought us to the point where we are."

Tony Clark

Former FERC Commissioner

Backers of the market structure contend that these policies unfairly disadvantage other generation technologies and raise prices for consumers. The result is a prolonged debate over how interstate electricity markets can accommodate state policy preferences, or whether states should reassert fuller control over their resource decisions.

That debate is now coming to a head at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in a case concerning how to treat subsidies in the nation's largest wholesale power market — the PJM Interconnection. Its outcomes could determine not only what plants are built today, but how the U.S. power sector evolves in the decades to come.

"It's the states who have said we are going to turn over the investment decisions to the market," said PJM CEO Andy Ott, whose subsidy mitigation plan is at the center of the debate. "Now they're coming back 20 years later and saying 'wait a minute, for this portion [of the market] we're going to make that call.' That's the issue."

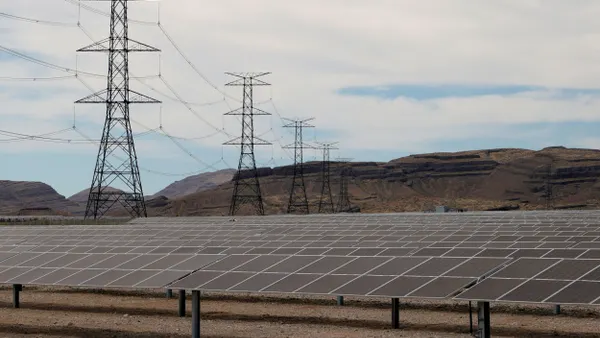

Power markets today

The U.S. is a patchwork of diverse electricity market structures. The traditional, vertically-integrated model persists largely in the southern, central and northwestern regions of the U.S., while 23 states and the District of Columbia have enacted some form of competition in generation, energy retailing or both.

Splitting generation away from the regulated utility dramatically changed how power plants were built in the states that undertook reforms.

Instead of a utility proposing generation investments that would be financed by its ratepayers, unregulated power producers would use shareholder money to build plants when they reasoned there was market demand for more electricity. The cheapest, most efficient plants would clear market auctions for power delivery, while those that did not would eventually retire.

But most states, particularly on the heels of the California energy crisis, were apprehensive to let market forces alone determine the generation fleet. In the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions, states established forward-looking capacity markets that secured generation capacity years in the future. While this added costs for consumers, policymakers reasoned the capacity markets would protect from generation shortfalls resulting from day-to-day market fluctuations.

Reliability issues were not the only concern for policymakers. As the 2000s progressed, rising public consciousness about climate change led a number of states to pass renewable energy mandates or institute carbon trading schemes. In other cases, states passed programs to protect plants within their borders on the grounds of employment and economic development.

All of these policies revealed a fundamental tension in restructured states. While policymakers want to take advantage of competition and market efficiencies, they also want to shape the generation mix that is the outcome of those forces.

"You can't be half pregnant but that's what we've tried to be."

Matt Larson

Partner, Wilkinson Barker Knauer

Even if they believe wholesale markets offer benefits over the vertically integrated model, many states also see them as delivering subpar outcomes in terms of pollution, fossil fuel reduction or state economic health.

"You can't be half-pregnant but that's what we've tried to be," Matt Larson, a partner at Wilkinson Barker Knauer, told Utility Dive in 2017. "We kind of like markets but if we don't like the outcome we're going to reverse it or start playing with prices … ultimately this is an area where the political economy pressures … overwhelm the ability to run a market."

That underlying tension between market forces and desired outcomes has been exacerbated in the last decade by the evolving costs of power generation resources in the U.S. Whereas large coal and nuclear plants previously set the marginal cost of electricity in wholesale markets, declining renewable energy costs and historically low natural gas prices have turned that situation on its head.

Today, natural gas plants typically set the prices in wholesale markets and are increasingly pushing more expensive plants offline. In 2005, coal constituted more than 50% of the U.S. generation supply, but that was down to 27% in the first half of 2018.

Nuclear plants, which cannot ramp up and down to vary their output, are similarly affected by the shift to gas and renewables. Six nuclear plants have retired in the last five years, and twelve more reactors — representing 11.7 GW — are slated to retire by the early 2020s.

Around-market extravaganza

Dissatisfaction with market outcomes has led many states and other parties to push for "around-market" policies to support their favored resources.

Coal generators FirstEnergy and AEP pressed Ohio and FERC for years to approve subsidies for their struggling plants, arguing that reliability would be at risk if they retire. When those appeals failed, FirstEnergy appealed to the Trump administration for a bailout this spring — one the White House devised, but has reportedly put on hold.

A number of states have also moved to subsidize existing nuclear generators, aiming to preserve their carbon-free power, high-skilled jobs and local tax contributions. New York, Illinois, New Jersey and Connecticut currently have support programs for their in-state nukes, and Pennsylvania lawmakers are considering a similar program.

On top of that, many restructured states have enacted renewable energy mandates to supplement the power sited through wholesale markets. Many of these are traditional renewable portfolio standard programs, but recently some states have become more prescriptive with their mandates. Massachusetts, for instance, has directed its utilities to purchase offshore wind and import hydropower from Canada to decrease their reliance on natural gas.

These state policies have drawn the ire of fossil fuel generators, who complain they depress market clearing prices for unsubsidized resources, cutting into their revenues. In 2016, generators filed court challenges against nuclear subsidies in New York and Illinois, and the same companies are supporting wholesale market changes at FERC that would raise prices to their benefit.

Recent federal court decisions affirming the New York and Illinois policies likely mean the task will fall to FERC to reconcile state policy preferences with the wholesale markets. Under the Federal Power Act, states have jurisdiction over generation within their borders, while FERC regulates interstate wholesale markets.

Fossil generators argued in court that nuclear subsidies breach the state-federal boundary by allowing subsidized nuclear plants to enter bids in capacity markets regulated by FERC.

The 7th and 2nd Circuit Courts, however, disagreed, ruling in September that nuclear subsidies do not defy state jurisdiction because they do not mandate participation in the capacity market for receipt of a subsidy. That precedent was established only in 2016, when the Supreme Court threw out a gas plant incentive program from Maryland in the Hughes v. Talen Energy.

The 2nd Circuit ruling also reaffirmed the legality of state renewable energy incentives. Given that FERC and the Department of Justice filed briefs in the 7th circuit case supporting the legality of state nuclear subsidies, most energy lawyers do not expect the Supreme Court to take up the case if generators decide to appeal.

"The courts are making clear they will not step in and save the markets absent a tie to the market analogous to Hughes," Larson told Utility Dive after the ruling. "It is all eyes on FERC."

FERC at the center

A number of concerns about state policy preferences are coming to a head in an ongoing proceeding at FERC over capacity market pricing in PJM, the nation's largest wholesale power market.

Last year, generators challenged PJM's market rules, arguing that nuclear subsidies in Illinois and renewable energy mandates were improperly suppressing capacity clearing prices. PJM responded by filing two reform proposals at FERC — a strict price floor and a capacity repricing scheme similar to what FERC recently approved to deal with subsidies in ISO-New England.

In a surprise decision, FERC rejected both proposals and threw out PJM's capacity market rules altogether, directing the grid operator to come back with a proposal that would allow subsidized resources to opt out of the market completely.

"The nuclear subsidies I think are really what brought us to the point where we are," former FERC Commissioner Tony Clark said at the time. "Barring the payouts to these big, dispatchable nuclear units, who knows if we would have reached this point where the commission really questions the entire capacity market construct."

Early this month, PJM filed its revised proposal, offering FERC two options.

PJM's first plan, the Resource Carve-Out (RCO), reflects FERC's suggestions, instituting a strict price floor and removing subsidized resources from the market. The second, "extended" proposal would boost capacity prices for the remaining resources by recalculating the market clearing rate after the subsidized plants are removed.

Ott said although FERC could choose only the basic RCO, it is meant to be combined with the extended proposal.

"We think that for the RCO here's all the details that need to be put around it to make it workable," he said. "We think there also is price suppression in the market so we think it's also necessary if you want a competitive market you need to add this other piece."

"FERC could come back and say 'we don't want a competitive market result,'" he added, "but frankly if you want to have a robust competitive market price you have to bolt on the repricing … It has to be part of it if you want a competitive outcome, and I personally want one."

"You're looking at the type of actions that really would impact the competitive market and only then would we have [the RCO] apply."

Andy Ott

CEO, PJM Interconnection

Approval of either of PJM's plans could have major impacts on determining which resources are installed in the mid-Atlantic market. Already, some analysts say the proposals could make it more difficult to site renewables.

"I think it creates a real challenge for large commercial and industrial customers willing to contract for renewables because the renewables provider supplying these customers can potentially no longer realize the capacity value of these renewables, which really creates investment cost recovery uncertainty," said Johannes Pfeifenberger, a principal at the Brattle Group, a consultancy.

"It's really a switch in market rules that creates significant investment cost recovery risks for the renewables developers," he said.

Ott said exemptions for small renewable energy resources in the plan mean it won't "materially be of impact" to most providers in PJM.

"[The RCO] has a 20 MW de minimis threshold, so no solar resource is going to fall within that, so it doesn't apply to that," he said. "You're looking at the type of actions that really would impact the competitive market and only then would we have [the RCO] apply."

On the other hand, if FERC makes it too easy for subsidized resources to opt out of the capacity market, generators like Calpine Corp. warn that the capacity market could become "purely residual," where most of the electricity in PJM is sourced through bilateral contracts.

That would be similar to the situation in California, Calpine wrote in comments, with "very high retail rates, very low wholesale rates and no investment that is not part of a state mandate.

States threaten exit

How FERC weighs state power preferences against market functions will have major impacts on the future of PJM and could set a precedent for how FERC will deal with similar issues in other regions.

Participation in PJM and other wholesale power markets is voluntary and some state officials are threatening to leave. If market reforms make it difficult for states to meet energy targets, some states may "justifiably seek alternatives", Illinois' head utility regulator warned in a Utility Dive op-ed.

"An unconventional, but potentially viable solution is for transmission owners currently in the PJM footprint to consider joining a neighboring RTO, such as the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO), or for the state to take on the management of market functions like New York and California," wrote Brien Sheahan, chairman of the Illinois Commerce Commission.

"If they fight [state] efforts, I think the markets will become less and less relevant in terms of supporting investments."

Johannes Pfeifenberger

Principal, Brattle Group

Ott said that far from curtailing state decision making, the RCO proposal aims to accommodate it in the market. Ott said he will issue a letter to states in the coming days calling for dialogue.

"There's a set of rules that need to be in place to allow the states to do what they need to do, but then we can protect the rest of the market from cost shifts and other things," he said. "So I think it's doing exactly what folks like Illinois is asking, but we have to work through a process."

How FERC will balance state authority with its jurisdiction over markets will not likely be clear until early next year, when a decision in the docket is expected. Pfeifenberger warned states may seek alternatives to the wholesale markets if PJM, FERC or other grid operators curtail clean energy participation.

"Customer and state policy preferences are really moving very strongly to the clean energy space. You see Apple and Google and Amazon and Walmart and all these C&I customers having strong preferences for renewable energy, and the states certainly do, and the [grid operators] can either support those efforts or fight them," he said.

"If they fight those efforts, I think the markets will become less and less relevant in terms of supporting investments."

Reply comments are due in the PJM proceeding Nov. 6.

This post has been updated to reflect reports that the White House has put a coal and nuclear bailout plan on hold.