Dive Brief:

- Automakers say they are engaged in a “range war,” adding energy storage capacity in order to win over electric vehicle customers concerned about how far they can drive their car or truck before needing to recharge.

- However, “you can't just pile on batteries” as the additional storage can quickly add to the vehicle price and weight, Rivian Senior Director of Public Policy Chris Nevers said last week at the Novi Battery Show, outside of Detroit.

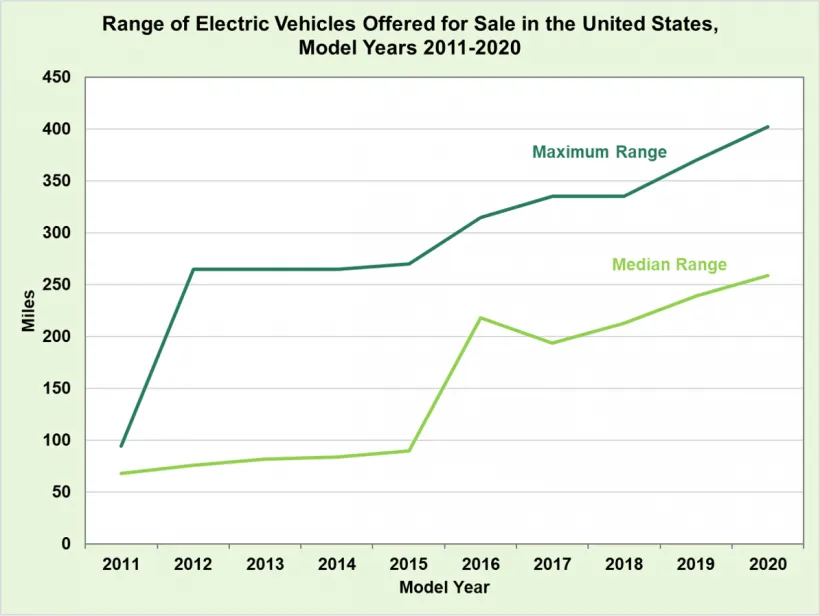

- The median range for new EVs is around 250 miles and has been rising for years. The 2020 model year was the first in which an EV achieved an estimated maximum range of more than 400 miles, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

Dive Insight:

Consumers will need access to a variety of EVs with different battery capacities and ranges in order to fully make the switch from internal combustion engine vehicles, automakers agreed at the Michigan battery conference last week.

“Consumers are always looking at a combination of attributes, price being always one of them, especially for vehicles,” said Michael Maten, director of EV policy and regulatory affairs at General Motors.

Roughly 300 miles of range is often considered a “tipping point” for customers to make the shift from an internal combustion engine to an EV. GM recently unveiled an electric 2024 Chevy Equinox, a mainstream crossover that can get 300 miles with certain specifications. Rivian, which focuses on trucks and off-road vehicles, offers its R1S with ranges that can exceed 320 miles.

Despite similar ranges, the Equinox starts at $30,000 and the R1S at $78,000.

“A 300-mile truck battery has a lot more kilowatt hours, a lot more energy storage, than a 300 mile Equinox battery,” Maten said.

“It’s not just the range. It's the energy capacity,” said Karl Plattenberger, chief engineer of powertrain and thermal systems at Mahindra Automotive North America. The company makes electric tractors.

“The utility companies are not just looking at this EV expansion as a demand they have to satisfy,” Plattenberger said. “It's also going to be critical with regard to sending energy back to the grid.”

Utilities are beginning to look beyond managed charging and demand response when it comes to EVs, to consider bidirectional flows of power and vehicle-to-grid applications to support the distribution system. New York City’s first vehicle-to-grid charging system went live in August in Brooklyn.

Longer-range vehicles will allow consumers to become electricity “arbitrators,” sending energy back to the grid when prices are high, Plattenberger added.