Electric trucks will accelerate on delivery, research and absorption into fleets in 2021, even though experts doubt more than a few Class 8 trucks will be delivered to carriers.

The electric truck is a crucial part of government and fleet plans to help decrease emissions. But implementation in the United States has been slow. In August, Wood Mackenzie estimated just over 2,000 electric trucks were in service at the end of 2019. The research firm said by 2025, the electric truck fleet will grow to 54,000.

The political winds and consumer tastes favor a change in how trucks are fueled. The new administration seems eager to help make the transition, and President Joe Biden campaigned on a promise of net-zero emissions in the U.S. no later than 2050.

Analysts said they don't believe 2021 will be the year a notable percentage — say, 5% or 10% — of Class 8 trucks become electric, but some predict this will be the year the change begins.

"I think 2020, last year, was the year of commitments," said Mike Roeth, executive director of the North American Council for Freight Efficiency. "If everybody says they will do what they say will do, this will happen pretty fast."

Roeth noted the pipeline for new electric trucks is slow in providing what fleets may want. That means what 2021 sees in the implementation of commercial electric vehicles won't be a flood — more like a trickle. But that will allow fleets to begin gaining experience with electric trucks: How to charge them, and learning the logistics of charging and range limits.

"What we will see is a lot of learning," said Roeth.

Electric in the lead over hydrogen

The speculation about how far electric trucks will advance in 2021 comes at a time when there is significant competition between two types of zero-emission vehicles.

On one hand, there are electric trucks. They have major boosters in Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla, who will deliver Tesla's first Semi trucks this year. Roger Nielsen, the CEO of Daimler Trucks North America, said in April 2019, at the Advanced Clean Technology Expo in Long Beach, California, that electric trucks were the future.

The other track is fuel-cell electric vehicles — or FCEVs. Hydrogen has better range than electric trucks, which are seen best used for drayage or short runs. Hyundai, Toyota, Navistar and Nikola are developing FCEVs.

Toyota and Hino Motors partnered last year to get fuel-cell-powered prototypes on the streets of Japan. Cummins and Navistar announced last November they would produce a Class 8 hydrogen truck that Werner would test for regional hauls in California.

But a national hydrogen strategy has problems, say critics, one similar to the problems that gasoline-powered cars had in the early days of development at the turn of the 20th century: Where does one get the fuel?

For electric cars and trucks, the answer is plug in. The electric infrastructure has long been built, and with some tweaks and expansions, will be able to accommodate electric trucks, which take between 1.7 megawatts and 1.8 megawatts to charge for an hour. That is a lot of juice.

"We still have real challenges," said Chris Nelder, the manager of Electric Vehicles-Grid Initiative of the Rocky Mountain Institute.

Nelder said it is easier to add power generation to the electricity grid, which is what he thinks will need to happen, than it is to add hydrogen fuel stations across the United States.

"There's no doubt in my mind that they will get there before the hydrogen infrastructure gets its shoes on," said Nelder.

The Rocky Mountain Institute released its report on how fleet managers can prepare for coming electrification, tellingly titled "A Steep Climb Ahead." But Nelder and other transport experts believe hydrogen trucks will have a steeper climb.

Speaking to analysts during Tesla's Q4 earnings call on Jan. 27, Musk said hydrogen had more drawbacks than electric trucks, even though Musk admitted battery production was keeping Tesla from going into full production of the Semi.

"People were saying that, somehow, hydrogen is going to be a better means of energy storage in a car than batteries. And it was like, this is just really not the case," Musk said.

Musk added that hydrogen "is not realistic" to keep in liquid form. And developing it into a fuel cell adds complications, he said.

"It's just crazy, basically," said Musk.

"There's no doubt in my mind that they will get there before the hydrogen infrastructure gets its shoes on."

Chris Nelder

Manager, Electric Vehicles-Grid Initiative, Rocky Mountain Institute

Other truck OEMs, such as Europe's Scania, have dipped their toes in the two energy pools. Scania researched FCEVs and put them on the roads, via customers. But Scania, in a Jan. 21 press release, said it is not betting on hydrogen in the long term.

"Going forward the use of hydrogen for such applications will be limited since three times as much renewable electricity is needed to power a hydrogen truck compared to a battery-electric truck," Scania officials said in the release. "A great deal of energy is namely lost in the production, distribution, and conversion back to electricity."

Blame immutable physical laws for the woes of hydrogen, Nelder said.

"When you convert energy from one form to another, you lose a little," said Nelder.

Producing hydrogen and getting it to fuel stations would be an intensive effort, in terms of labor, distribution and production, he said. And FCEVs are not efficient in getting power from the engine to the wheels.

For those reasons, electric trucks will take more market share than hydrogen, said Nelder.

The fleet attraction of electric

Right now, it's not very competitive between electric and hydrogen. Excluding research vehicles, there are few, if any, hydrogen-fueled trucks on the roads in North America, said Tim Denoyer, ACT Research vice president and senior analyst.

There were 2,000 heavy-duty electric vehicles on the road at the end of 2019. Denoyer believes the total number of heavy-duty electric trucks and buses on North American roads will rise to 4,000 units by the end of 2021.

And in other classes, many electric units are ready to go. "You can go buy an all-electric Class 6 garbage truck right now," said Nelder.

The infrastructure-ready aspect of electric trucks is attractive to fleet managers. So is efficiency, according to Denoyer.

Electric trucks are more efficient than FCEVs in terms of power transferred from the battery to the wheels, he said. Further, there are maintenance benefits to electric trucks. A new technology can come with higher maintenance costs, as it is more complex, but Denoyer said electric trucks' complexity compares favorably to the complexities needed for diesel engines.

There are issues with electric trucks, though. Electric-truck batteries are heavy. And the purchase cost for a new electric truck is higher than a new diesel-powered truck, said Denoyer, by as much as 40% to 50%.

"Even with that, the total cost of ownership is lower," said Denoyer. "Because you are going to spend less on fuel and maintenance over the life of the vehicle."

Denoyer said the savings show up later in, for example, school buses. Even if paying 50% more for an electric school bus, the fuel and maintenance — and the total cost of ownership — are 25% less than a diesel-powered bus. Medium-duty electric trucks also show a lower total cost.

But for now, only some Class 8 applications show a lower total cost of ownership, said Denoyer. They include spotters, drayage and short-haul applications. Diesel, he said, still rules the highways.

"Diesel is going to have a cost advantage for longer-haul highway freight for some time," said Denoyer.

Electric's ideal applications

Even with diesel's cost advantage, the winds of change are moving fleets to speed up electrification. Denoyer said he believes electric adoption is going to accelerate. Orders for electric heavy-duty trucks are increasing, as fleets accept that electric Class 8 trucks are ideal for short runs — less than 150 miles. But for now, electric adoption "is a lot easier in Class 4 through 7," Denoyer said.

An ideal application would be utility trucks, which never wander too far from base, and whose owners usually have access to electric chargers, said Denoyer.

And the utilities themselves see the growth in commercial trucks needing chargers and megawatts as a business opportunity, and will likely assist fleets in setting up charging stations, as they ensure there is enough power.

"You are going to spend less on fuel and maintenance over the life of the vehicle."

Tim Denoyer

ACT Research vice president and senior analyst

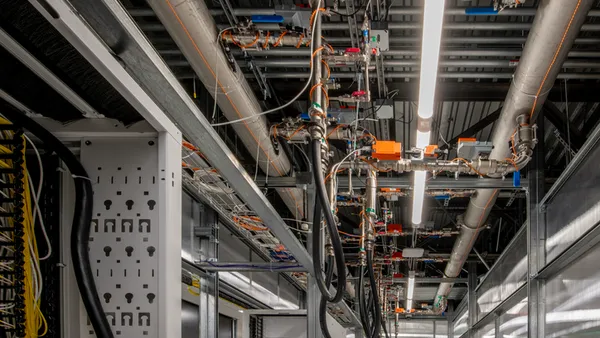

Daimler is helping fleets make the decision by prepping infrastructure. On Dec. 1, PG&E and Daimler announced the creation of "Electric Island," a charging site for medium-duty and heavy-duty electric trucks. Daimler officials said the island will have nine vehicle-charging stations.

Roeth points to other adoptions that indicate greater plans are in place. In Modesto, California, Frito-Lay is working on converting a 500,000-square-foot facility into a zero-emissions freight hub this year. The transition will cost $30.8 million. Part of Frito-Lay's investment will go to infrastructure, renewable energy generation and power storage capabilities on-site.

"They took that whole site and turned it into zero-emission," said Roeth.