The energy transition’s new resources, technologies and voices require the utility integrated resource plan, or IRP, to be better, many planners and analysts say.

An IRP is the strategy a utility submits to its regulators every one to three years in most states for investing in reliable affordable power and meeting its policy goals and obligations. But new approaches, like those being explored by Arizona Public Service, or APS, and Duke Energy Indiana, are needed to meet upward pressures on rates, stakeholder calls for clean energy options and equity, and federal and state policies, many regulators and stakeholders agree.

“Market forces are shaping utility resource portfolios,” acknowledged Commissioner Pat O’Connell of the New Mexico Public Regulation Commission. “But this moment of change is an opportunity to go big on high-level IRP reforms with more analysis of more factors,” he added.

For APS, “the changing landscape requires transparency with stakeholders in the IRP process,” said APS Vice President of Resource Management Justin Joiner. “That means coming to planning sessions with stakeholders without answers, because two heads are better than one, and decisions about affordability, reliability and clean energy can best be reached with diverse stakeholder viewpoints,” he added.

Reform efforts to introduce best practices like all-source solicitations, distribution system planning, and engaging new voices could add more work for already overburdened utility planners and regulators, some said. But developing integrated system planning with state-of-the-art modeling that optimizes solutions to today’s reliability and affordability challenges will be easier than undoing bad planning decisions, others responded.

A “reimagining” opportunity

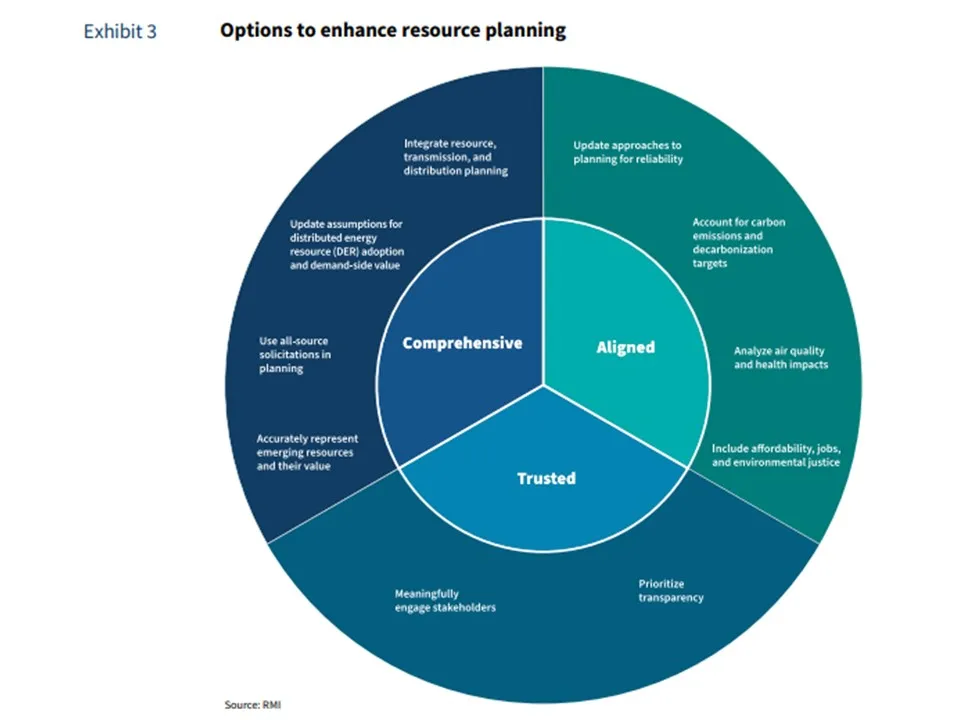

Utility “planning processes are being stretched and challenged” to meet the power system’s emerging dynamics, according to a new report from independent analyst RMI. But utilities, regulators and stakeholders can “shape the future electricity system” by “reimagining” IRP “rules and guidelines,” to make planning more comprehensive, transparent, and aligned with policy, RMI said.

Through 2025, “utilities serving at least 40% of U.S. total electricity sales and over 90 million customers” will file IRPs with “over $300 billion” in proposed system investments, the report said. That is an opportunity “over the next 10 to 30 years” to integrate new operations, resources, and technologies to meet projected demands “at least cost, while mitigating risk and meeting policy objectives,” the report added.

The RMI report expands on and confirms a wide-ranging 2021 call by regulators from 15 states and Puerto Rico for planning “to evolve to meet new technologies, changing costs and stakeholder demand,” said National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners Senior Director, Center for Partnerships & Innovation, Danielle Sass Byrnett.

State policy “should be part of planning,” stakeholder engagement is “vital,” and utility regulators should “establish rules for the IRP at the outset of the planning process,” the Task Force on Comprehensive Electricity Planning report from members of NARUC and the National Association of State Energy Officials, or NASEO, said.

Proposals for improved planning will differ by state regulatory regime and state policy, the NARUC-NASEO paper said. They will also differ by the proposed reforms’ complexity, enforcement provisions, and requirements for stakeholder engagement, it added.

IRP reforms should move toward transparent utility data, thorough regulatory review, and greater stakeholder participation, the RMI paper said. Reforms must also align with traditional utility priorities like reliability, affordability, and safety while meeting new state and federal policies and customer calls for reduced emissions and increased equity, it added.

The burden that major IRP scope, rules, and participation reforms could add to already time and cost-constrained regulators and utilities is “the single biggest pushback to the paper,” RMI Principal, Carbon-free Electricity Practice, and paper co-author Lauren Shwisberg said. But “taking on that burden now can significantly reduce future planning burdens” like the complexities of sophisticated computer modeling, she added.

IRP reforms like new planning frameworks that include new technologies, resources, and improved stakeholder engagement have produced significant ratepayer savings and policy compliance, Shwisberg added.

Stakeholder input challenging the need of a natural gas plant in Xcel Energy’s 2016–2030 Upper Midwest Resource Plan led to Xcel’s revised 2020–2034 IRP, RMI said. The resulting lower-cost plan could save ratepayers $372 million over the planning period, it reported.

From 2016 to 2022, the Georgia Public Service Commission has developed a robust stakeholder ecosystem, “with nearly 20 parties engaged” in recent three-year planning cycles, RMI reported. Over that period, Georgia Power’s proposed natural gas additions dropped and its renewable resources had “a 200% increase,” the paper said.

“That is an example of how a commission can use leverage, if the IRP rules support it,” said Southern Renewable Energy Association Executive Director Simon Mahan. “The RMI report shows many ways good commissioners can develop new IRP rules that will create a legacy of protection for ratepayers that outlast them.”

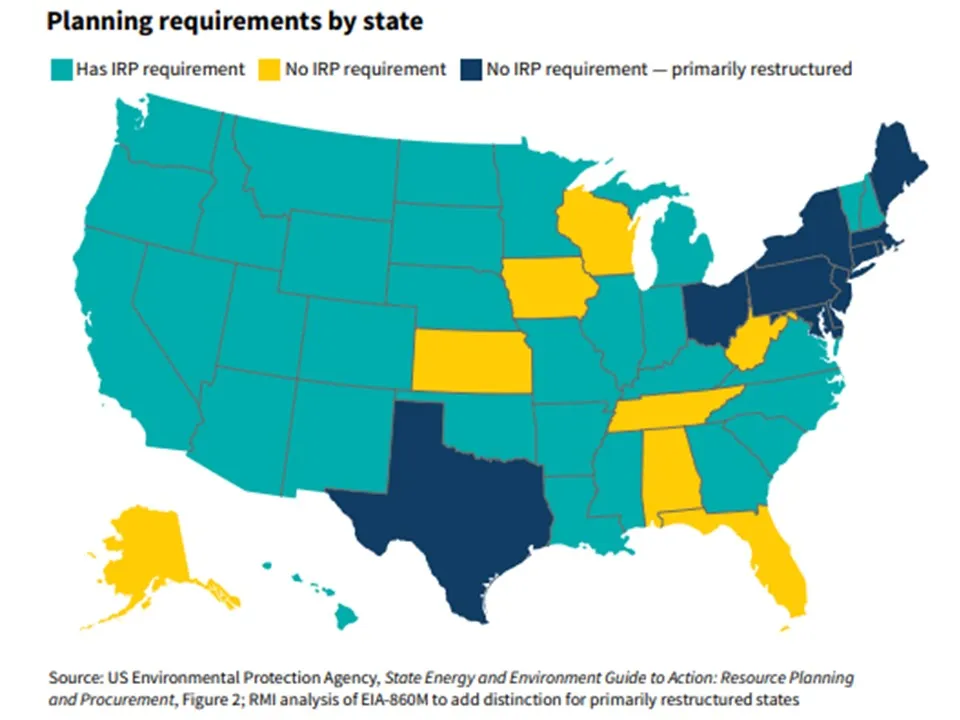

“We are planning an electricity system with new and different needs, options and goals,” RMI’s Shwisberg said. “But almost half of utilities still are not required to do — or don't do — fully transparent, aligned and comprehensive planning, even though it will make the IRP process more useful to all participants, and this paper is a challenge to regulators and utilities to update planning,” she said.

Policymakers’ planning innovations

A few states have essentially no IRP requirement and others limit IRP requirements to some utilities, like those that are investor- or publicly-owned, RMI reported. In many of the states leading in innovations, like Minnesota, Washington, Colorado and South Carolina, regulators and legislators require IRPs from most or all electricity providers, it added.

State legislators can influence critical parts of planning rules like regulatory review and use of stakeholder input to approve, provisionally approve, or call for adjudication of a plan before accepting or rejecting it, RMI said. Even progressive commissions like those in Oregon and Washington use policy mandates as guidance, it observed.

Oregon’s House Bill 2021 requires that utility IRPs submitted to the commission provide a Clean Energy Plan for achieving the bill’s mandated clean energy and emissions reductions, said Oregon Public Utilities Commission Spokesperson Kandi Young. In response, Oregon regulators approved an order that provides “guidance for what’s to be included” in the utility plans, she added.

Washington state’s 2019 Clean Energy Transformation Act (Senate Bill 5116) similarly led to the ongoing guidance from Washington state regulators. New rules define compliance with 100% clean electricity and require it by SB 5116’s 2045 target date. They also guide implementation of requirements for affordability, reliability, equity, emissions reductions, and more transparent electricity markets.

“Planning has evolved,” and once hypothetical best practices conceived to avoid bad outcomes, like nuclear investments with severe cost overruns or time delays, now can put “all possible resources on a level playing field,” said Regulatory Assistance Project Senior Associate Elaine Prause, a former Oregon commission staffer and PacifiCorp senior planning manager.

“It probably is not possible to quantify the value of planning, but without a shared vision unwise investments are more likely,” Prause said. Having worked with Oregon’s commission and at PacifiCorp, “it is clear both utilities and regulators are facing change and need new processes to achieve those better outcomes,” she added.

“With new processes and stakeholders, things may take longer, but more and different perspectives allow the commission to build the best and most comprehensive record,” she said. That is not the same as paralysis of decision-making, because the best decision-making takes time and these new processes are necessary, Prause said.

“The utility owns the IRP, regulators and policymakers inform it,” and “affected stakeholders” must be engaged, said New Mexico Commissioner O’Connell. But current reliability and affordability planning scenarios in many utility planning processes “are too vague” and lack a specific “destination” like “being carbon-free by a certain date or always having sufficient capacity to enable economic development,” he said.

“One of the facts of the regulatory world is that all participants have limited resources, and planning reforms could add complexity," O’Connell recognized. “But today’s technologies make new things possible and that means there may not be a choice except to reimagine planning for those new possibilities,” he added.

More stakeholder input “can lead to conflicts when utility data does not support a stakeholder’s assumed outcomes,” O’Connell acknowledged. But the RMI report shows “this is a moment of big change that will require working hard to understand those challenges, even if it means doubling the number of people working on planning and tripling the computing power,” he added.

Utilities and stakeholders in planning

Some utilities are working closely with policymakers and regulators to rethink planning.

Avista Utilities’ developed its IRP to comply with the Clean Energy Transformation Act and the commission’s implementation rules, and has found “the new rules set requirements that help facilitate the plan,” said Avista Spokesperson Mary Tyrie. Like Avista, Puget Sound Energy’s IRP is focused on implementing state policy “in the most efficient and equitable way possible,” said PSE spokesperson Andrew Padula.

But many utilities still pursue integrated resource planning independently and that has left some stakeholders dissatisfied with utility efforts to integrate clean energy and reduce fossil fuel dependence.

“Generally, it is still up to individual Southeastern utilities to follow IRP best practices and unfortunately many have not been cooperative partners,” said Southern Renewable Energy Association’s Mahan, who has worked in IRP processes across the region.

“Better rules can require utilities to adhere to their filed plans and allow commissions to order utilities to redo plans deficient in justifying information,” Mahan said. Reforms can also allow regulators to require utilities to issue competitive all-source solicitations “which essentially replaces modeling with a market test that shows exactly what the least cost resources are,” he added.

Conclusions in such reformed IRP processes do not guarantee their proposed resource investments in General Rate Cases will be approved, but can help, RMI said. Few states approve reimbursement for capital investments through rates based on IRPs, requiring instead that utilities show investments are reasonable and prudent in the rate case, it added.

A commission-endorsed IRP strategy built with greater stakeholder engagement that includes a more diversified resource mix “can give the utility some confidence in its proposed investments” when it goes to the rate case, said Duke Energy Vice President, Integrated System Planning, Mark Oliver.

Duke Energy Indiana avoided overbuilding natural gas generation and emissions growth by 2021 stakeholder-driven changes to its 2019 preferred resource portfolio that substituted solar and storage additions for natural gas plants, RMI reported. “Indiana stakeholders made their voices heard and influenced planning” and that kind of participation has allowed Duke to approach planning “in a broader and more integrated way,” Oliver said.

Federal and state policies are key planning factors, but “Duke has learned the value of customer-owned resources, storage, and transmission through scenarios run by its new Encompass modeling tool,” Oliver added.

“Most widely used modeling tools are not up to the new IRP complexities,” but Duke’s relatively new EnCompass tool “points in the right direction” by modeling the broadest portfolio of solutions,” said Strategen Consulting Director Erin Childs.

And there are ways to narrow the complexity of planning, Oliver said. “Go after demand-side opportunities for flexibility first, procure clean resources wherever possible, always protect reliability and affordability, and use an all-of-the-above approach to clean resource procurements to hedge against uncertainty and reduce risk, especially for beyond 2030,” he added.

Though not highlighted by RMI, Arizona has had “strong planning rules” since 2010 that have allowed its utilities to consider distributed energy resources, and air quality, report co-author Shwisberg said. Their stakeholder engagement “processes have become even more transparent over time,” she added.

“We continue to look for every opportunity to improve the IRP process,” added APS’s Joiner. The utility expanded its transparency by providing access to its Aurora modeling tool to several participants in its Resource Planning Advisory Council and “allow them to see and evaluate all our planning inputs and suggest changes or run their own hypotheticals,” he added.

Reviewing multiple modeling scenarios “is a significant time and staffing” commitment, but “it ensures the planning process is doing what it is intended to do,” Joiner, who previously worked in planning at Indiana and Illinois utilities, added.

“In the other states, the best efforts were used to find the best solutions, but too often decisions were made without stakeholder input, and did not produce dialogue and planning development,” Joiner said. “When stakeholders are engaged early and often and if planning begins without any assumed answers, the outcome is more likely to be transparent, trusted, and comprehensive,” he added.

Correction: We have updated this story to correct the location of Puget Sound Energy, which is in Washington, and the spelling of the name of PSE spokesperson Andrew Padula.