Editor’s Note: We have updated this story with additional comments from DOE's announcement Tuesday.

Dive Brief:

- Scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory have achieved net energy gain in a fusion experiment, paving the way for a technology that could someday provide clean and plentiful energy, the U.S. Department of Energy announced Tuesday.

- Physicists have sought since the 1950s to harness nuclear fusion reactions to generate energy, but no group until now has produced more energy from the reaction than it consumes, which is known as net energy gain or target gain.

- Kim Budil, director of Lawrence Livermore, said at the announcement at DOE headquarters in Washington it will be years before fusion ignition will be commercially available.

Dive Insight:

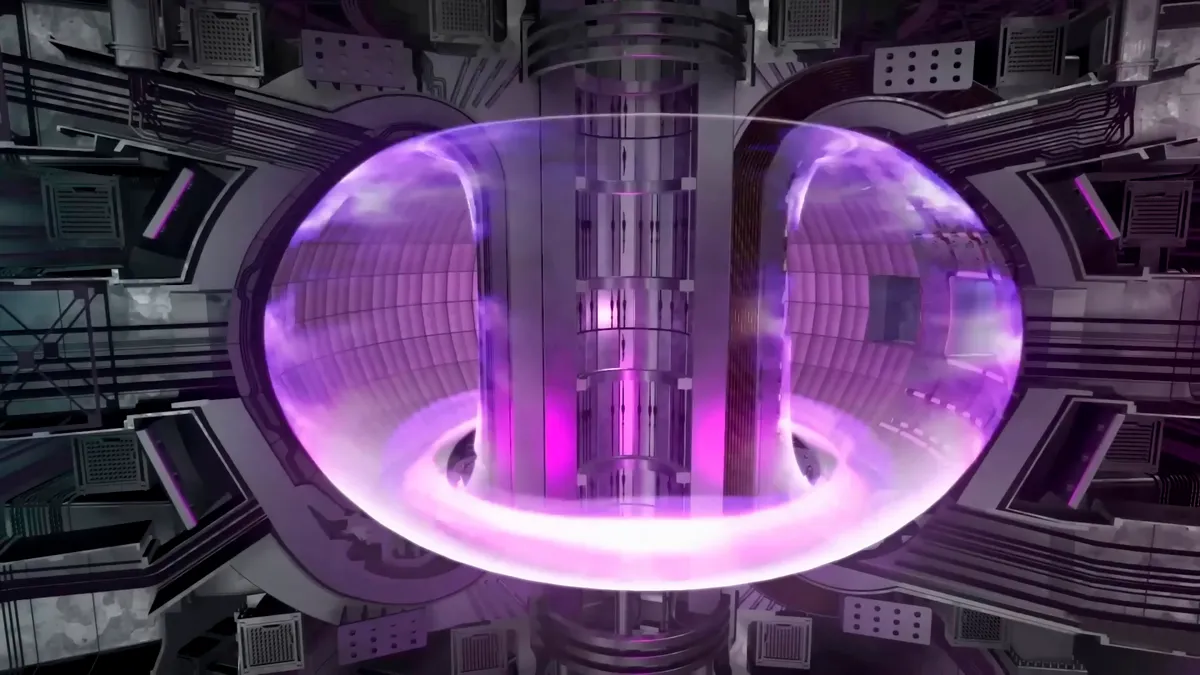

Fusion works by combining light atoms, such as hydrogen, into heavier products, such as helium, releasing tremendous energy extracted as heat that holds the key to producing energy. Some waste is produced, but less than what is left behind in a nuclear power plant.

Scientists and Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said the development “will pave the way for advancements in national defense and the future of clean power.”

“The pursuit of fusion ignition in the laboratory is one of the most significant scientific challenges ever tackled by humanity, and achieving it is a triumph of science, engineering, and most of all, people,” Budil said.

Research into fusion has made progress in recent years with broad applications of 3-D printing allowing low-cost production of parts used by fusion machines and numerous designs for testing.

Budil detailed to reporters following the announcement the time and work needed to commercialize fusion ignition.

“There are very significant hurdles, not just in the science, but in the technology,” she said. “This is one igniting capsule one time and to realize commercial fusion energy you have to do many things. You have to be able to produce many, many fusion ignition events per minute and you have to have a robust system of drivers to enable that.

Commercializing fusion ignition will probably take decades, Budil said.

“Not six decades I don’t think. Not five decades, which we used to say,” she said. “I think it’s moving into the foreground and probably with concerted effort and investment a few decades of research on the underlying technologies could put us in a position to build a power plant.”

Andrew Sowder, senior technical executive at EPRI, the Electric Power Research Institute, said the announcement is a “big deal” because scientists have tried for decades to draw out more energy in research than is put in. “For the first time, it really shows that a reaction can produce more power than it consumes,” he said.

“Maybe it's anticipated, but it's always like many things: a surprise when it actually happens,” he said in an interview Monday.

Sowder said the initial success with fusion energy is comparable to the space program when it launched some 60 years ago.

“I would say this would be kind of like getting the first man in orbit,” he said. “You’re not to the moon yet, but you’ve shown you can get the person in space and they survived and they came back alive. This is kind of a first step.”

The real work now begins to “turn it into something that can produce economic, practical electricity for the grid and possibly other uses,” Sowder said. “The hard part is building a machine to make something reliably and cost-effective, something that's competitive with other sources.

“It has to be cost-competitive to make it to market,” Sowder said. “The beauty of fusion is it checks a lot of boxes,” Sowder said. “It produces energy when you want it to, it’s a small package, no carbon. It's scalable.

“This becomes an important tool in the toolbox for energy as well as for climate concerns. The more tools you have the better,” he said.