Dive Brief:

- Building automation systems, distributed energy resources and other grid-interactive efficient building, or GEB, technologies must be developed and operated with robust cybersecurity protections, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Federal Energy Management Program said in a fact sheet released Oct. 14.

- Federal facilities managers must assess potential risks posed by GEB systems and understand how they can affect data confidentiality, integrity and availability at the buildings where they are deployed, according to FEMP’s cybersecurity fact sheet.

- “Most cybersecurity stakeholders are largely thinking about IT and how to protect data and information,” DOE Energy Technology Program Specialist Jason Koman said in an email. “At FEMP, our program is really focused on … devices that operate in the real world and can have physical consequences if they are compromised.”

Dive Insight:

FEMP released the fact sheet following its Federal Smart Buildings Accelerator last month, which provided education and technical support services to promote energy and cost-saving smart building and GEB technologies across federal facilities.

GEBs can generate up to $200 billion in savings across the electric power system through 2040, DOE said in a roadmap for grid-interactive efficient buildings released in 2021.

A decarbonized electric grid requires a “dynamic, two-way relationship between buildings and the grid,” ASHRAE said last November in its own roadmap for GEB deployment.

GEBs “utilize smart technologies, renewable energy sources, and energy storage systems to optimize energy consumption and generation…[allowing them] to respond in real-time to grid signals, thereby reducing overall demand and [greenhouse gas] emissions,” Kent Peterson, chair of the ASHRAE task force for building decarbonization, said in a news release announcing the organization’s roadmap.

This year, the federal government has announced several initiatives in support of the Biden Administration’s goal of cutting 65% from federal operations’ greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and achieving a net-zero federal building portfolio by 2045. In January, DOE allocated $104 million for clean energy, energy conservation and net-zero projects at 31 federal facilities. The U.S. General Services Administration in June announced an $80 million investment in smart building technologies that can improve energy efficiency. In August, the GSA updated its building design and construction standards and performance criteria to accelerate energy efficiency and decarbonization in more than 300,000 federal buildings.

“Federal facilities are deploying both GEB and [distributed energy resource technologies] around the country,” Koman said.

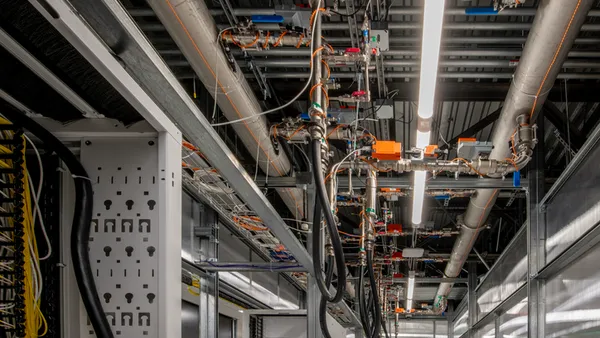

For example, the Carl T. Hayden Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Phoenix deployed a 4.4-MW solar array capable of supplying 28% of its power needs, a 1.5-million gallon chilled water tank for peak load management, and direct digital air handler controls that cut air conditioning electricity use by 45%, according to a FEMP case study. An upgraded building automation system and advanced data management enabled load shifting, reducing the center’s energy consumption by more than 25%, FEMP said.

GSA estimates that it will save $13.5 million and reduce total energy use by 41% at the Oklahoma City Federal Building after outfitting the five-building campus with nine GEB technologies, including a solar array, a battery energy storage system and lighting controls, according to a separate FEMP case study released in March 2023.

FEMP developed the cybersecurity fact sheet for GEBs “to stay in front of vulnerabilities and to help agencies overcome barriers to deployment we know they will face,” Koman said.

GEB systems are “operational technology” that can have real-world safety and security impacts if compromised, beyond what disruptions to information technology systems might cause, Koman said.

For example, “What happens if a chiller system is run to the point of critical failure and then a federal facility is down because it cannot be cooled?” he asked.

In terms of potential risks related to GEB systems, one example involves distributed energy resources such as bidirectional electric vehicles, which “have complex system boundaries and require additional assessments during technology specification, procurement and deployment stages to accurately identify, document and mitigate cybersecurity risks,” FEMP said.

FEMP’s Distributed Energy Resources Cybersecurity Framework provides building managers with a starting point to conduct fundamental cybersecurity governance, technical management, and physical security assessment, FEMP says. Its distributed energy resource risk manager is another tool that operators can use to navigate and implement the widely-trusted NIST Risk Management Framework for IT security, according to the fact sheet.

Federal cybersecurity compliance requirements assign responsibility for digital security to a broader range of stakeholders than just facilities managers, FEMP noted. These include GEB technology manufacturers that “will be required to add several security functionalities to protect federal agency data and infrastructure,” FEMP said.

The fact sheet also mentions “research pathways” for grid-efficient building technologies. Though FEMP has nothing to announce on that at this time, “we are aware that cybersecurity is a major factor in making our facilities smarter and more flexible, and we are actively looking to address that more robustly,” Koman said.

Additionally, FEMP plans to “bring GEB to a broader group of federal facilities [with] focus on recognition for planning and execution of demand flexibility projects at specific sites and at an agency or regional level” through its Demand Flexibility Challenge program, which it expects to launch next spring, Koman said.

“We have studied GEB and demand flexibility and there are plenty of sites within the [United States Government] that already use them, so now it is time to bring them to the broadest group of facilities where it makes sense,” he said.

Interested in more facilities management news? Sign up for Facilities Dive’s newsletter today.