This is the seventh in an occasional series from AEE that addresses how the power sector can successfully transition to a 21st Century Electricity System.

U.S. utilities invest over $20 billion per year replacing and modernizing their electricity distribution infrastructure. As the electricity system continues to evolve, making sure that this money continues to be invested wisely, especially at a time of growing deployment of distributed energy resources (DER), is prompting changes to how utilities conduct distribution system planning.

The distribution grid is the backbone of a reliable electric system used to deliver electricity from the transmission system to individual consumers. Modern planning processes are critical for providing essential electric service.

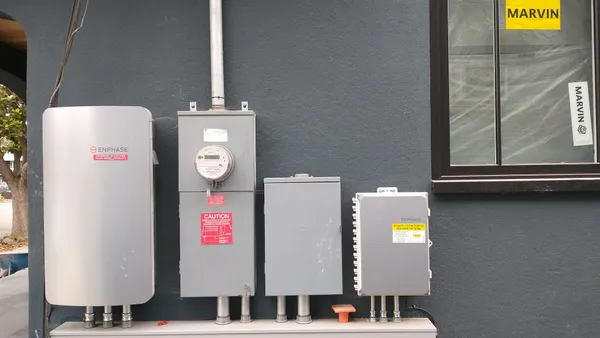

The distribution grid also enables interconnected DERs to export electricity and provide grid services, provides electric service when distributed generation (DG) systems are not generating, and provides critical grid stability — maintaining voltage and frequency. Enhancements to the distribution system, particularly the deployment of digital technologies, are providing grid operators with more visibility into, and control of, the system.

As DER deployment continues to grow, utilities and the DER industry are seeking ways to maximize the benefits of DERs to the system, while maintaining reliability and reasonable costs for customers.

In many states, utilities and DER providers are coming together to consider how DERs can be more fully integrated into the system, allowing utilities to take advantage of the benefits DERs can provide and optimizing distribution system planning and investments to account for and include DERs.

The figure below shows which states are actively investigating and implementing changes to their distribution system planning practices. Some examples include:

-

In April, staff of the Missouri Public Service Commission submitted a report in the Commission's comprehensive modernization proceeding with recommendations to develop a more detailed analysis on the needs, costs and benefits associated with DERs and the development of an integrated distribution system planning process. Following the report, the Commission issued for comment draft rules regarding the treatment of distributed resources to facilitate a more holistic distribution system planning process.

-

Also in April, the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission staff issued a report that proposed draft integrated distribution plan processes for the state's utilities. Filing requirements differ by utility but include: 1) planning objectives, 2) processes for developing distribution plans, including stakeholder engagement, 3) baseline distribution system, DER deployment and financial data requirements, 4) hosting capacity and interconnection requirements, 5) DER futures analysis, 6) long-term distribution system modernization and infrastructure investment requirements and 7) analyses of non-wires alternatives.

-

In May, the Connecticut Public Utilities Regulatory Authority set the scope of its distribution planning process and has been holding a series of workshops to investigate changes. Specifically, the process is covering the key cost drivers of maintaining and modernizing the distribution system, how demand and consumption patterns are changing and how distribution system planning can change to address these needs, and the current state of the grid and what is needed to optimize the grid of the future.

-

In September, the Public Utilities Commission of Nevada issued a proposed decision that would require utilities to file a resource plan every three years that includes a distributed resource plan. Key parts of the distributed resource plan include: 1) load and DER forecasting, 2) locational net benefits analysis, 3) a grid needs assessment to identify and screen grid upgrades and 4) a hosting capacity analysis.

-

In September, the Michigan Public Service Commission staff filed a report making recommendations for a distribution planning framework. Key recommendations included: 1) requiring multiple scenario load forecasting and probabilistic planning, 2) requiring publicly available hosting capacity information, 3) requiring utilities with advanced metering infrastructure to utilize Green Button (i.e., providing access to customer usage data), 4) requiring plans to provide detailed information on criteria for non-wires alternatives projects, 5) requiring the development of a common cost-benefit methodology and 6) requiring plans to contain workforce adequacy and development plans.

AEEAlthough every state has different goals, legal requirements and market conditions, and therefore takes a somewhat different approach to distribution system planning, a practical framework would include four key components:

1. Distribution System Capabilities, Needs and Constraints. This includes utilities identifying and communicating the hosting capacity on different parts on the system, identifying where adding certain types of DER would be most beneficial and increasing access to certain types of non-sensitive system information to enable non-utility stakeholders, including customers and third-party DER providers, to help meet grid needs.

2. Load Growth Forecasts, DER Forecasts and Scenario Analysis. Forecasting is evolving to include more granular projections of DER potential and likely customer adoption, and should include robust scenario analysis and probabilistic planning of DER penetration to ensure a thorough understanding of future risks and opportunities.

3. Integration of DERs. To more fully integrate DERs, policymakers and utilities should identify opportunities to standardize and streamline interconnection processes, adopt and implement interoperability standards, and make grid modernization investments to maintain and enhance the reliability and flexibility of the grid.

4. Framework to Properly Value and Source Services from DERs. To evaluate DERs on a level playing field with traditional resources and infrastructure investments, a regulatory structure should be developed to properly value and source services from DERs.

All of this will require careful attention on the part of regulators and utilities, taking into account interactions between the distribution system and the bulk power system. Enhanced visibility and control at the distribution level can facilitate the integration of large-scale renewable generation and also enable aggregated DER to provide services to the bulk power system, provided there is appropriate planning and coordination.

Distribution system planning that proactively anticipates more distributed assets at the grid edge will help chart a path to a 21st century electricity system. If done properly, a framework that emerges will lead to a more flexible, reliable, resilient, cost-effective and clean electricity grid.

AEE's issue brief, Distribution System Planning: Proactively Planning for More Distributed Assets at the Grid Edge, as well as seven other related issue briefs, are available for download at http://info.aee.net/21ces-issue-briefs.