The following is a contributed article by William Hughes, a principal research analyst who leads Guidehouse Insights' Building Automation and Control solution.

It seems obvious that when a homeowner replaces an old appliance or fixture with a more efficient model, it is always a good thing. Surprisingly, it is not so clear-cut. A number of studies have found that some kinds of residential energy efficiency retrofits not only do not result in significantly less power usage but end up increasing power usage. The positive news is that many utilities are offering solutions to address this challenge by using disaggregation tools to offer homeowners information as to why their energy bill increases rather than drops.

Many people are proud of being environmentally conscious

Before postulating a solution for this dilemma, it is important to understand the underlying drivers behind this counterintuitive situation. The primary reason is that people are often excited about their new, energy efficient purchases and want to enjoy them. This behavioral tendency has been observed by academics and is called the Khazzoom–Brookes postulate. In the 1970s, economists Daniel Khazzoom and Leonard Brookes noticed that people were trading in their gas-guzzling cars for more efficient vehicles, followed by a tendency to drive these new vehicles more often than the previous ones.

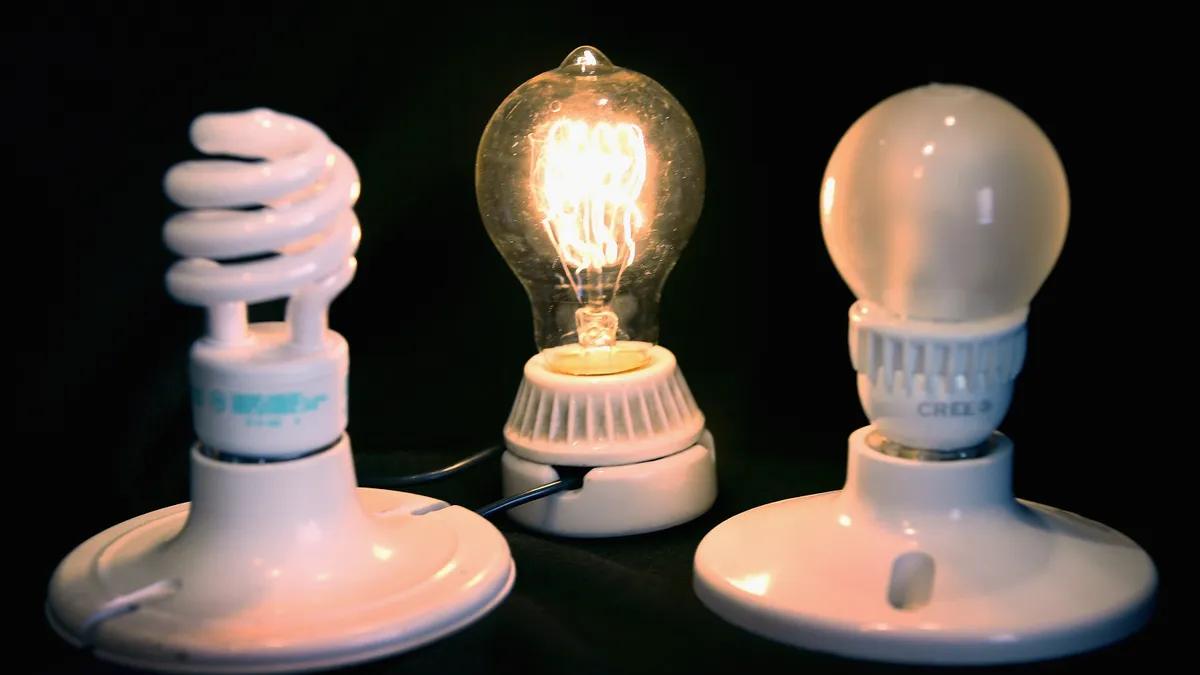

This finding is not a case of your mileage may vary when referring to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) fuel economy labels posted on new cars. The postulate notes a change in behavior with a net result of increased fuel consumption, although the miles per gallon efficiency is better. Applying this scenario to the home, the EPA states that residential LEDs "use at least 75% less energy … than incandescent lighting." The EPA estimates that complete conversion to LED lighting in the US would eliminate the need for annual electrical output of 44 large electric power plants.

If people use LED lighting the same amount as they used incandescent lights, it reasons that power use for lighting would drop by 75%. Instead, in the report "Are Residential Energy Efficiency Programs Effective? An Empirical Analysis in Southern California," a team from UCLA evaluated the power usage of millions of homes in Southern California and found that actual energy savings was less than 1%. The numbers indicate that the people who get LED lights that use 25% of the power of incandescent lights end up leaving on the LED lights about four times as long.

This report also found that new energy efficient dishwashers and washing machines resulted in higher energy use. Previous generations of dishwashers and washing machines offered users a manual option to select smaller or larger loads. Newer product generations of machines can sense load sizes and automatically adjust the amount of water that is required. Although this feature has inherent benefits around water conservation, electricity consumption does not vary significantly by load size. This finding is consistent with the behavior described by the Khazzoom-Brookes postulate. It is likely that people are taking advantage of doing additional loads with smaller amounts of dishes or laundry.

The researchers at UCLA cited 10 other studies that also found energy efficiency investment did not meet the level of expected savings. For example, National Bureau of Economic Research reports "Do Energy Efficiency Investments Deliver? Evidence from the Weatherization Assistance Program" and "How Effective Is Energy-Efficient Housing? Evidence from a Field Experiment in Mexico" illustrate that assuming homeowners will use new appliances in the same manner they used old appliances is not an accurate assumption.

Is it wasteful or are people getting more value from their energy efficient purchase?

An economist may look at this situation and conclude that the homeowner is getting more value from their investment. This outcome is positive. Conscientious homeowners may have been turning off incandescent lights as much as possible to conserve energy. With LED lights, they may be enjoying the illumination along with the sense of being responsible for using a more efficient lighting option. They may also be lulled into the idea that the LED is so much more efficient that it is not worth the effort to turn off a light. It is not possible to know the details of the motivation for this behavior.

Similarly, a homeowner with a new, energy efficient washing machine may change their behavior and prefer to run smaller loads. Doing so keeps the laundry piles from becoming burdensome. For example, if they ran an average of 10 loads monthly at $0.30 per load for electricity with the old machine, it would cost $3.00 monthly (10 x $0.30). They then buy a new washing machine and do 20 smaller loads monthly at $0.20 per load. Their bill went from $3.00 up to $4.00 (20 x $0.20).

Disaggregation is the solution

A homeowner may regret spending money on a new appliance marketed as being more efficient only to see their electricity bill increase. It may be difficult for the homeowner to discern such a slight increase of one dollar specifically for their washing machine. However, utilities are increasingly providing disaggregation data that breaks out major uses including appliances and lighting.

This detailed information tells the homeowner that their new appliance investment is not lowering their power usage as expected. In the case of the washing machine example, it would show them the cost of their electricity for this appliance went up 33% from $3.00 to $4.00.

The disaggregation data can provide useful information to the homeowner. It can show them the change in their behavior where they doubled the number of loads. It can also show them that the average cost of the new appliance compared with using the previous appliance decreased by 33% from $0.30 to $0.20.

Everyone wins when homeowners have information

Presenting this type of granular analysis is particularly important when utilities offer marketplace services to their customers. Customers may be unsure whether to trust suggestions from utilities because they represent a change from the traditional transactional relationship. Without the awareness that they are running twice as many loads, some customers might see a higher electrical bill and assume that the utility's energy efficient appliance recommendation was a ploy to get customers to buy more electricity. Their trust in their utility would decline.

With additional information about the change in their number of loads, customers would realize that they should not blame their utility for the higher electricity bill for the washing machine. Some homeowners would choose to make the environmental choice to only run full loads. They would see their bills for the electricity used by their washing machine decrease. The trust in their utility and its marketplace would increase.

The rest of the customers that enjoy the convenience associated with smaller loads would have the information to understand that they have a choice. They can run full loads, or they can run small loads. In either case, the per load cost is lower. Their trust in their utility and its marketplace would also increase.

Greater trust encourages additional purchases

Utilities are implementing disaggregation solutions for their customers. Often, doing so supports their efforts to better target new services and offer products that will help customers reduce their electricity usage. For example, disaggregation can identify when a homeowner acquires an EV. Many utilities offer programs that both lower the cost of electric vehicle charging to the homeowner and allow the utility to serve this demand with lower cost power.

If homeowners trust their utility, they are more likely to take advantage of this offering. Homeowners might pass on this program if they feel distrust and animosity with the utility and its marketplace. Adding information that shows their usage patterns before and after for new products adds credibility to energy efficiency efforts, particularly if it is a solution recommended by the utility. It can also reduce the chances of missed energy efficiency savings described by the Khazzoom-Brookes postulate.