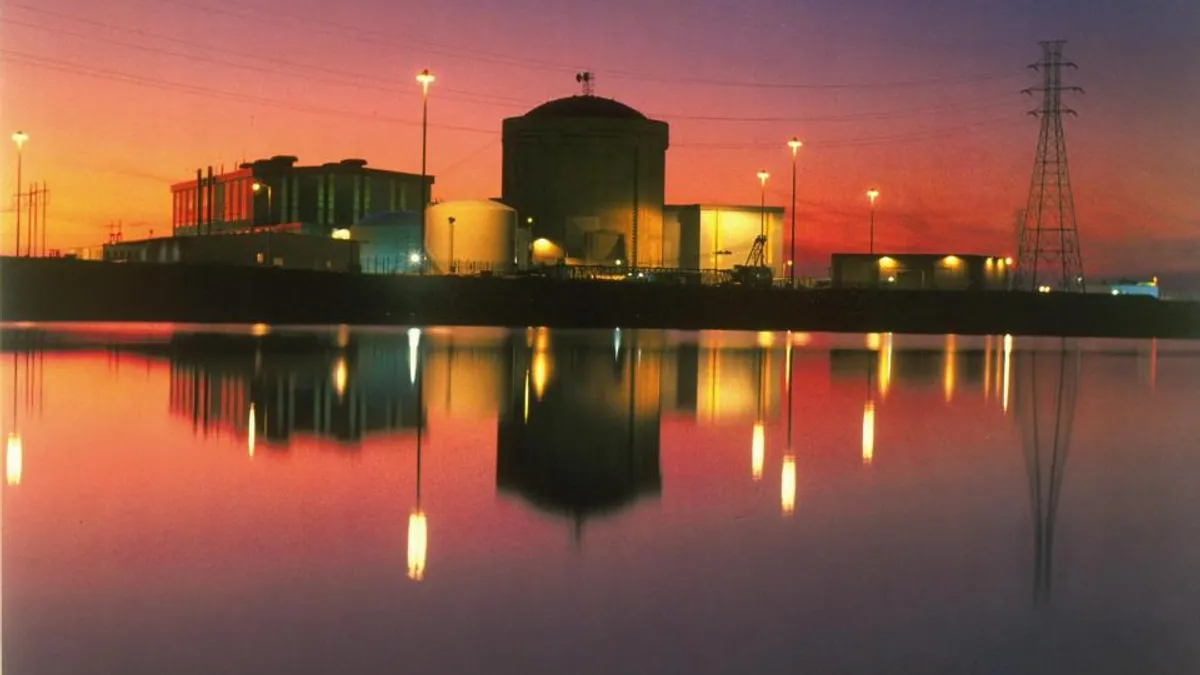

The expansion of the V.C. Summer nuclear plant was supposed to provide low cost, emissions-free electricity to residents of South Carolina for decades. But following the owners’ decision to abandon construction, the only thing the two planned reactors will be generating is higher rates.

On July 31, Santee Cooper and SCANA Corp. subsidiary South Carolina Electric & Gas pulled the plug on construction in Jenkinsville, ending a multi-year saga of repeated delays and cost overruns.

"The credibility of the nuclear power industry has taken a direct hit,” said Peter Bradford, a former commissioner with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and past chair of the New York and Maine state utility regulatory commissions.

The usual argument for building a nuclear plant, or any power plant, is that the benefits outweigh the costs, Bradford said. With the Summer project “customers are getting the costs without any benefit.”

The original cost estimate for SCE&G’s share of the project was $6.3 billion, set in March 2009. The estimate was amended in November 2016 to $7.7 billion with new in service dates for the two reactors of Aug. 31, 2019, and Aug. 31, 2020. The amended price was based on a revised fixed price engineering-procurement-construction contract from Westinghouse Electric of $3.345 billion.

Santee Cooper’s original cost estimate for its 45% share of the project was $5.12 billion, amended to $6.2 billion in 2016.

But the delays at Summer and Southern Co.'s Vogtle nuclear plant in Georgia put financial stress on Westinghouse, and it filed for bankruptcy on March 29, 2017. That made it clear that the contractor would likely reject the EPC contract for Summer, leading to further cost increases.

Months of negotiations ensued on a variety of issues related to the continuation of the Summer project. On July 27, SCE&G and Santee Cooper reached an agreement under which Westinghouse’s parent company Toshiba agreed to pay the partners damages associated with rejection of the EPC contract.

SCE&G’s 55% share of that award comes to $1.2 billion or $700 million after taxes. Santee Cooper’s share of the award is $976 million.

SCE&G now says the cost to complete the project is $8.8 billion, or $1.1 billion more than the last estimate.

Santee Cooper says it has spent $4.7 billion on the Summer project, and with the Westinghouse bankruptcy it estimates the project would not be finished until 2024 and would cost a total of $11.4 billion for its share — 75% higher than the original cost.

Santee’s board felt that “was something we could not put on customers,” spokeswoman Mollie Greer said.

With the expansion dead, the two utilities say they will now turn to efforts to minimize costs to customers. But analysts and lawmakers are already speaking out against their plans — particulary SCE&G's ability to earn a return on its sunk costs — and it remains to be seen how the debacle will affect the prospects of another at-risk nuclear build in Georgia.

Death of a nuclear build

Santee Cooper took the lead in pulling the plug on Summer. But after the agency’s board made its decision, SCE&G felt it had no choice but to follow suit. SCE&G said it was not feasible for it to carry the financial burden of the project on its own.

In an ex parte hearing at the South Carolina Public Service Commission on Aug. 1, it became clear executives from SCANA, SCE&G's parent, would have been to complete one unit of the Summer plant and build a gas-fired baseload plant instead of the second reactor. SCE&G estimated the cost of that option at $7.1 billion.

In its release, Santee Cooper was less definitive than SCE&G, saying it was “ceasing operation” and leaving the door open for government intervention or a new partner. SCE&G was more definitive, saying it would file an “abandonment plan” with the PSC.

During the ex parte hearing, SCE&G made clear that it held no hope for government aid or intervention or that a partner would be forthcoming.

SCE&G CEO Kevin Marsh said that the partners had tried, without success, to elicit aid from Washington for four months running up to the decision to abandon. He also said that earlier attempts to find a new partner had been unsuccessful.

So, far Santee Cooper ratepayers have paid $540 million for the now abandoned project. Most of the total $4.7 billion cost of the project has been financed — that is, paid for by issuing bonds. Ultimately ratepayers end up paying the cost of whatever bonds the state-owned agency issues.

Greer says Santee Cooper is “looking at how to mitigate future costs to customers.” One immediate measure would be flow back to ratepayers the proceeds from the Toshiba award.

In a filing with the PSC, SCE&G requested that it be allowed to recover the $5.3 billion in costs incurred for its share of the Summer project, less $316 million for transmission assets built for the nuclear expansion that it will be able to put to use. That comes to $4.9 billion to which SCE&G is seeking to add another $220 million for demobilization costs for the July 31 to Sept. 30, 2017, period. The utility is still evaluating the post-Sept. 30 costs of winding down the project.

SCE&G says those rate increases would be mitigated “for a number of years” by using its $700 million award from Toshiba to reduce rates to customers in the near term. But ratepayers might not see a decline in their bills because ratepayers have yet to be billed for 15 months of construction work in progress (CWIP) payments. SCE&G expects the payments to offset each other and keep rates flat.

Beyond that, though, SCE&G is asking regulators to allow it to spread the remaining costs of the defunct project over 60 years. SCE&G is also asking the PSC to approve future rate increases to cover the cost of replacing the capacity that would have been provided by the nuclear units.

Right now SCE&G is purchasing 300 MW as a “bridge” through 2019, which is being amortized at $10.8 million a year.

The 60-year amortization plan would minimize the near-term impact on ratepayers, said Paul Patterson, an analyst with Glenrock Associates. But the plan raises questions.

The 60 year amortization is “ridiculous,” said Mark Cooper, senior research fellow for economic analysis at the Institute for Energy and the Environment at the Vermont Law School. Under that amortization plan, SCE&G would be able to treat Summer’s sunk costs as a regulatory asset that would earn a return of about 10% for the next 60 years.

SCE&G did not respond to requests for comment.

Alternatively, he recommends that ratepayers should try to “claw back” as much as they can from the utility by shortening the recovery period and pursuing an imprudency ruling at least on the amounts spent in the last year or so.

The decision to abandon the Summer project did not sit well with South Carolina officials. In the ex parte hearing PSC Chairman Swain Whitfield took SCE&G executives to task for blindsiding the commission.

Local legislators also slammed the utility. A recently formed bipartisan group called the South Carolina Energy Caucus gathered at the statehouse on Aug. 2 to condemn the nuclear debacle that will have to be paid off for generations. The also said they plan to investigate SCANA for improper management practices.

Exacting consequences on SCANA could prove difficult. The state legislature in 2007 passed the Base Load Review Act, which allowed SCE&G to bill customers for the nuclear plant as they built it, rather than after it comes into service. The law also allows the utility full cost recovery if the plant is not built.

“We have given the utilities more of a blank check than we ever should have,” Rep. Kirkman Finlay (R) said at the gathering, according to The Post & Courier. Finlay earlier this year sponsored a bill that would roll back the BLRA.

Over the river

Across the border in Georgia, Southern Co.’s Georgia Power utility and its partners are building a similar nuclear project. Like Summer, the Vogtle nuclear expansion also calls for two AP1000 Westinghouse reactors and used the developer as its EPC contractor.

Vogtle’s owners also have won an award from Toshiba, which has agreed to pay them $3.68 billion ($1.7 billion to Georgia Power) whether or not the project is completed.

Vogtle’s owners are facing many of the same issues that Summer’s owners faced, but Southern Co. CEO Thomas Fanning seems undeterred in his dedication to finishing the two reactors at Vogtle.

During an Aug. 2 earnings call, Fanning pointed out the differences between Vogtle and Summer. He noted that the commercial terms for the projects are different, as are the EPC costs, the guarantee, and the regulatory processes.

Fanning acknowledged that “people are going to be interested in comparing our situation to SCANA’s,” but said with all the differences “It really is apples and oranges.”

That said, Vogtle’s owners are still looking at a higher cost project as a result of Westinghouse’s bankruptcy.

“I think on a lot of scenarios going forward with nuclear may make sense. Of course, we may decide not to and we'll see,” Fanning said, adding that it would not make sense to replace the reactors with gas units because that would involve building a “lengthy” gas pipeline.

Fanning now puts the project’s total costs in a range of $18.3 billion to $19.8 billion, though in a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Southern put the total cost as high as $27 billion.

Fanning said Southern and its partners — Oglethorpe Power (30%), MEAG Power, (22.7%) and Dalton Utilities (1.6%) – plan to file a recommendation with state regulators on how to proceed with the project.

In the earnings call, Fanning laid out a “go” scenario in which Southern’s share of the cost would be between $6.7 billion and $7.4 billion to finish the project, or $1 billion to $1.7 billion more than originally budgeted. In the “no-go” scenario, Fanning said it would cost about $6.3 to abandon, costs that the utility company would seek to recover from ratepayers under a law similar to South Carolina’s BLRA.

Fanning also noted the regulatory and legislative considerations that have to be taken into a decision to abandon.

“The other thing that remains is your long-term relationship with the state general assembly, the regulators, everything else, because when you abandon, you have nothing to show for the amount of money you've spent,” he said.

Cooper said he thinks the Summer abandonment will “give policymakers pause” in Georgia and press them to look for ways to protect ratepayers.

But so far, Southern still seems to enjoy good relationships at the Georgia PSC. Commissioner Doug Everett told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution he has “100% confidence” that Southern’s nuclear arm can complete the Vogtle project. And in a July 31 statement, PSC Chairman Stan Wise said, “ratepayers would be understandably upset if they got nothing in [new power] generation for the billions that have already been spent.”

Wise also highlighted the differences between Vogtle and Summer. He noted that the rate impact from Vogtle will be spread over three times as many customers (Georgia Power vs SCE&G) and that rate impact has so far been much lower for Georgia Power customers — 5%, compared with 18% for SCE&G customers. He also noted that Vogtle negotiated a higher payment from Toshiba, $3.7 billion vs. $2.2 billion, and that Vogtle’s costs are spread among four partners while Summer’s are share between two partners.

Wise said he wants the PSC to be ready to make an up or down decision on Vogtle by Dec. 5.