Connecticut regulators and stakeholders are building a new utility regulatory framework to achieve state policy goals and make electricity more affordable but utilities say they could be misguided.

The Connecticut Public Utilities Regulatory Authority, or PURA, phase one final decision (Docket 21-05-15) on performance-based regulation, or PBR, was released April 26, 2023. Like the landmark Hawaii 2021 PBR framework it drew on, the Connecticut decision adopted goals, foundational considerations and priority outcomes for a controversial regulatory “paradigm shift” to a new utility business model.

Connecticut’s “legacy business model,” and traditional regulation of utilities are “fundamentally at odds” with today’s technologies, policies, and accelerating adoption of distributed energy resources,” the decision said. The state’s utilities and regulators fully agree on this premise but differ over the resolution.

“There is potential for PBR to work out well,” but “the current regulatory environment seems overly punitive,” said Douglas Horton, vice president, distribution rates and regulatory requirements, for Eversource Energy, Connecticut’s dominant investor-owned utility. “Lowering the utility return on equity and replacing it with performance incentives” could “have drastic ramifications,” Horton cautioned.

“Utilities should welcome PBR because it gives them tools to earn from better performance,” responded PURA Chair Marissa Gillett. “It specifically tells utilities what is expected of them and how to demonstrate that performance, which is a level of certainty they have never had,” and “more helpful guidance toward earnings than how to achieve cost recovery in a rate case,” she added.

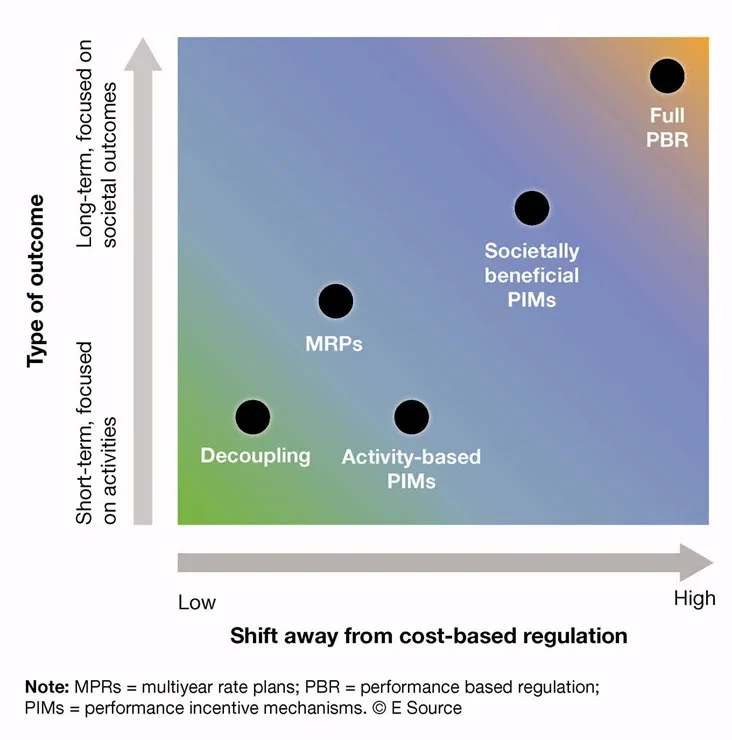

Other states like Illinois and New York have limited and targeted performance-based measures that better align utility and customer interests, but Connecticut is expanding on Hawaii’s work by undertaking even greater comprehensive regulatory reform, analysts agree. Many stakeholders support PURA’s customer-focused plan, but reduced utility revenues could impede urgently needed investment in distribution system infrastructure upgrades, the state’s IOUs said.

Connecticut’s PBR

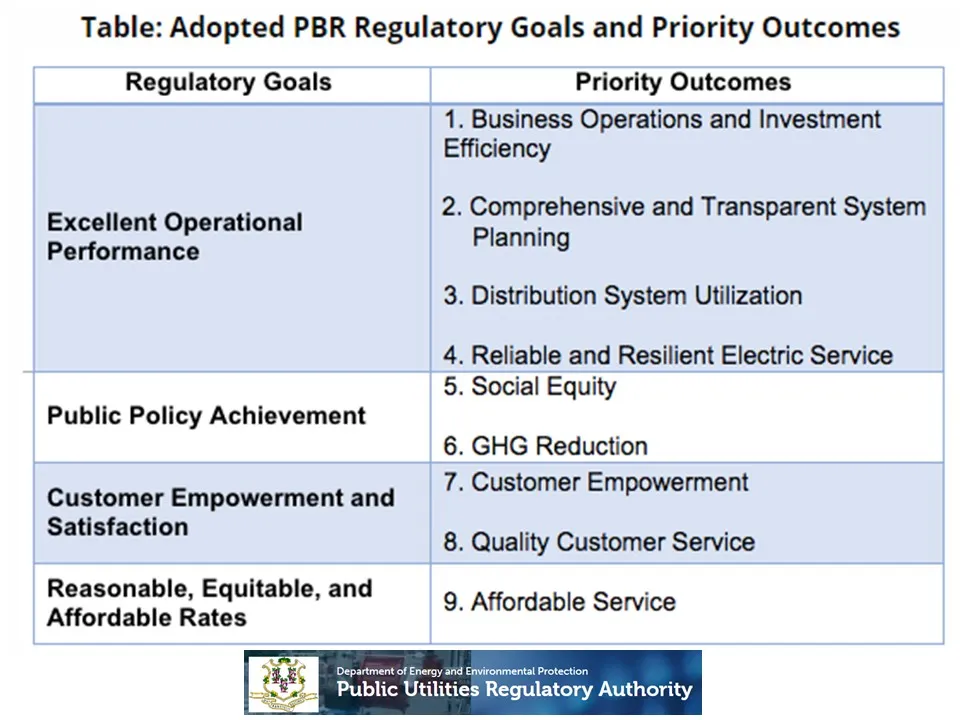

Like Hawaii, Connecticut’s phase one objective was to begin its new and comprehensive regulatory transformation with key goals and foundational considerations linked to priority outcomes for utilities, Chair Gillett said.

The goals are better utility operations, meeting public policy goals, better customer service, and reasonable, equitable and affordable rates, the final decision reported. It acknowledged the goals “may require” new utility investments that impede achieving affordable rates “in the short-term.” But “tension between regulatory goals is an inherent aspect of utility regulation,” it added.

“Connecticut’s Governor and lawmakers want this regulatory reform because of frustrations with high electricity rates, but they recognize infrastructure investment is needed to reach state policy goals,” Chair Gillett said. Hawaii investors and stakeholders told introductory PURA workshops that “certainty, predictability, and clear rules,” can lead to investment community commitment, she added.

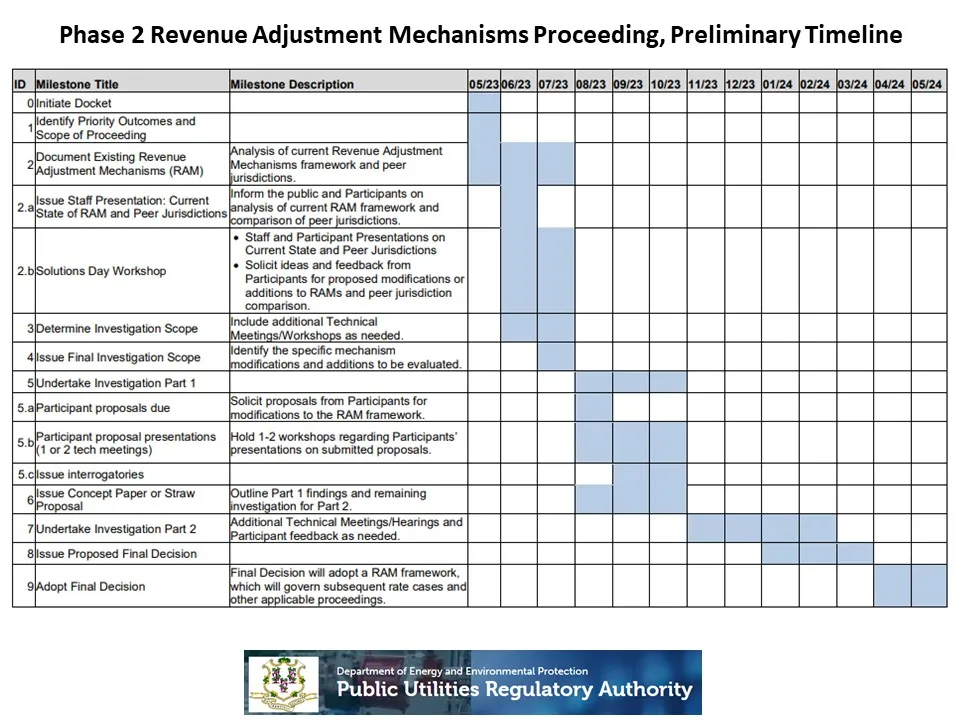

Stakeholders in Connecticut are deep into the first docket of phase two (Docket 21-05-15RE01) of the PBR process, examining how utility revenues will be earned and shared. It could guide “the remainder of the PBR investigation” and the state’s future utility regulation, according to the phase one decision. But it is leading to heated stakeholder differences about whether there are adequate protections for utilities and their customers that do not appear to have easy solutions, most stakeholders agreed.

The overall process will have three phases, expected to be completed by the end of 2024. Discussions on performance metrics, scorecards and performance incentive mechanisms, or PIMs, are getting started as part of the second docket of phase two (Docket 21-05-15RE02). And the concept of a preliminary integrated distribution system planning, or IDSP, design, is being developed in a third docket (Docket 21-05-15RE03).

As interest in PBR elements, and especially PIMs, accelerates around the country, regulators, utilities and other stakeholders in many states have ongoing work that has informed Connecticut, Gillett and others said.

Other PBRs

There were at least 24 state regulatory PBR actions in the North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center, or NCCETC, October 26 Grid Modernization policy update. But the many other states working on PBR are taking significantly more limited approaches than Connecticut is taking on, said NCCETC Associate Director, Policy and Markets, Autumn Proudlove.

Many IOUs, including Xcel Energy Colorado, Central Maine Power and Unitil Massachusetts, have proposed PIMs, NCCETC found. PIMs are being studied in Illinois, North Carolina and New Hampshire. Broader PBR proceedings are ongoing in Arizona, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota and Iowa. In other states, utilities or regulators have considered PIMs for energy efficiency, battery storage and resilience.

The main lesson from other states is a warning, said Conservation Law Foundation, or CLF, vice president and director, Connecticut, Shannon Laun. PBR is “unlikely to be effective without a comprehensive shift from cost-of-service ratemaking to a comprehensive performance-based framework,” she added.

But Connecticut has learned additional important lessons from other states.

“In the same way New York and Hawaii are still working to improve performance mechanisms, we want a PBR framework that allows making adjustments to PIMs or adding PIMs, Gillett said. “The intent is to communicate to all stakeholders that they can expect changes and how to seek them,” she added.

Illinois equity provisions showed how PIMs can drive equity performance, Consumer Counsel Claire Coleman of the Connecticut State Office of Consumer Counsel added.

“Connecticut is improving Hawaii's work, with the metrics and incentives for equity Hawaii postponed,” said Strategen Consulting Partner, Executive Vice President, and Head of Consulting Services Matthew McDonnell, who acted as legal consultant to the Hawaii commission and is doing the same for PURA.

“In Hawaii, skeptics said PBR was for distribution utilities and in Connecticut they are saying Hawaii showed it is for vertically integrated utilities, but PBR can be designed to suit any market structure,” McDonnell said.

Recent phase two discussions have raised a question many stakeholders agree could determine the direction of PBR in Connecticut: Should utilities have PIMs for outcomes over which they have limited control?

The big debate: Control

An emerging debate over what outcomes utilities can impact may be pivotal, just as it was in Hawaii, analysts agreed.

“It is clear there are different opinions on whether utilities should have PIMs for outcomes they don't view as within their control,” Chair Gillett said. The purpose of this docket is for each stakeholder to provide persuasive evidence to the record supporting their position,” she added.

Hawaiian Electric’s concerns about control “showed additional PIMS would be needed” to create revenue opportunities for the utility “based on performance instead of on traditional cost recovery,” said Strategen Director of Regulatory Innovation Jennifer Potter, a commissioner with the Hawaii Public Utilities Commission during its PBR development and approval.

The utilities’ concern with control and financial interests is understandable, acknowledged Vote Solar Regulatory Director, Northeast, Lindsay Griffin and CLF’s Laun. Some utility control of outcomes is necessary with a PIM, the Connecticut Office of Consumer Counsel agreed in an August filing. But the need for 100% control narrows the potential of PIMs to drive outcomes, Consumer Counsel Coleman added.

Traditional cost-of-service ratemaking has prevented rates “too high for customers,” and rates “not too low for utilities to remain financially sound,” said Eversource Energy’s Horton. “PBR with those goals can align utilities’ incentives with state policy and customer concerns,” he added.

But PURA’s PBR framework would be “punitive if it included penalties for things not within a utility’s control and quantifiable against a measured baseline,” Horton said. Eversource estimates that costs for generation, transmission service, and meeting policy goals leave only about 25% of a customer’s bill in a distribution utility’s control, he added.

Penalties and rewards for managing that 25% “would absolutely be acceptable, but it is not clear if that is PURA’s intention,” Horton said.

Because of PURA’s work on PBR, S&P Global Regulatory Research Associates found, Connecticut’s uncertain regulatory environment for utilities has become “one of the lowest ranked in the U.S.,” Horton said.

PURA’s ratings “will improve significantly once PBR is in place and stakeholders realize it benefits utilities and their customers and meets Connecticut policy goals,” Chair Gillett responded. Meanwhile, “the sky is not falling, and Eversource just reported record-breaking profits,” she added.

But “it is important not to expect rates lower than they are today,” Gillett continued. Significant capital expenditures will be needed to modernize Connecticut’s aging infrastructure, but “PBR can keep rates lower than they otherwise would have been because the utilities will have incentives to achieve the best outcomes for customers,” she added.

The first of Avangrid subsidiary United llluminating’s four core principles for PBR design “is that utilities must have control of outcomes for which PIMs require them to use resources, time and energy,” said Daniel Canavan, vice president, regulatory affairs, for the smaller of Connecticut’s IOUs.

PIMs “should also be based on objective metrics,” that have been “tracked over time” because new metrics could be distorted by “unique events,” Canavan said. And, “PURA should tread cautiously when using customer resources to achieve an outcome not shown by a cost-benefit analysis to provide more customer benefit than it costs,” he added.

Adequate data will be needed to set PIM baselines, both Consumer Counsel Coleman and CLF’s Laun agreed.

“Stakeholders do not want utilities to be accountable for what they cannot control, though 100% control is perhaps a bridge too far,” Laun continued. But the threat to utilities “is not completely clear” because “PBR will only negatively impact the utility if it fails to meet the performance standards,” she added.

Other stakeholders see the utility concern with control as doubts about the viability of eliminating the financial certainty of returns guaranteed by cost-of-service ratemaking.

The real debate: Money

PURA’s phase one decision called for a paradigm shift to equalize utility biases between the capital expenditures that earn returns on equity, or ROE, and less capital-intensive performance-focused expenditures.

Part of regulation is to make utilities perform more “like competitive businesses,” said Regulatory Assistance Project, or RAP, Senior Associate Mark LeBel, the lead author on a new RAP study of PBR’s potential. “Higher ROEs are good policy only if the utility earns them,” he added.

If utilities perform well, “they should expect to earn more than the cost of equity and reward their investors,” but “if they perform poorly, they should expect only the cost of equity, or perhaps less,” LeBel said.

“Discussions about lowering the ROE and replacing it with PIMs are “unsettling,” said Eversource’s Horton. It is not clear that will provide utilities a market-competitive ROE that will “attract investor capital,” he added.

Equalizing incentives for capital expenditures and operational expenditures “would not necessarily increase the utility’s earnings,” Horton said. It “adds a new return component” which could work against affordability and make IOU financials less investor friendly, he said.

PBR could make it “difficult to attract the capital needed to upgrade Connecticut’s aging infrastructure,” Horton continued. If PIMs are inadequate to meet utilities’ revenue requirements, failing infrastructure could cause PBR to “collapse under its own weight,” he said.

The utilities’ concern about their revenue requirements is legitimate, said Strategen’s McDonnell. “Hawaii spent almost two years setting its revenue mechanism,” and Connecticut “may spend the entire next phase of the proceeding” addressing that concern, he added.

But the goal of PBR is to protect the utility's financial integrity while also accurately calibrating risk between utilities and customers,” Strategen’s McDonnell continued. “That does not mean zero utility risk” or “insulating utilities from the responsibility to perform at a high level to earn PIMs,” he said.

PBR requires utilities to face more uncertainty about their revenue requirements than traditional regulation, McDonnell acknowledged. Guardrails that ensure protection against unintended outcomes can allow them to focus on understanding the risks and opportunities in the rewards and penalties for performance, he said.

PURA understands the importance of the utilities’ financial integrity, McDonnell said. “The cost-of-service revenue requirement is the starting point in building a PBR framework that allows utilities to learn to secure earnings with PIMs,” he added.

“The utilities financial stability and integrity are important to PURA because state law obligates it to recognize how that bears on utilities’ services to ratepayers,” Chair Gillett said. “But I am an activist regulator because a regulator with a different regulatory philosophy is needed to meet the policy goals of the Governor and the legislature,” she added.

“PBR will provide the certainty and clarity that investors want and that utilities need to work with it,” Gillett continued. And “Connecticut utilities’ credit and financials will remain stable or improve when PBR is fully implemented, just as they did for Hawaiian Electric,” she added.