The rise of renewable energy is now “inevitable” and clean energy sources will soon be the “norm,” Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz recently told a group of the world’s energy ministers.

Considered fringe technologies less than a decade ago, wind and solar energy are steadily becoming competitive with traditional generation, making them an increasingly attractive investment for power providers in states like Colorado or Texas, even when compared with natural gas.

But as quickly as that revolution in the power system became commonplace, another is picking up steam.

The next big change, already in the works and raising urgent questions, is the aggregation of distributed energy resources (DERs) into a reliable grid resource. The growth of distributed generation is expected to top that of new central-station plants worldwide after 2018, according to a recent Navigant Consulting report.

Providers say it is time to remove the obstacles to using software-managed fleets of distributed resources like rooftop solar and behind-the-meter battery storage to meet grid needs, just as a traditional generator would. Already, some pilot programs are underway in states like New York, California and Hawaii.

With power sector leaders and regulators all working to form new market rules for the distributed energy future, a recent report of industry insiders from GTM Squared sheds light on many of the obstacles they face.

The report, “Annual Survey Report 2016: The Future of Global Electricity Systems,” highlights four key areas of concern that need to be answered before aggregated DERs can become a broadly marketable product:

-

The real value of DERs in electricity markets;

-

Whether DERs managed by third parties present a threat to electric reliability;

-

If and how utilities and build a new business model by competing in the DER marketplace;

-

Whether third-party providers or utilities are better positioned to aggregate and market DERs.

The survey finds few concrete answers, but, according to utilities and DER providers queried by Utility Dive, there are some areas of agreement where consensus might be built.

Limited consensus

For its report, GTM Squared surveyed 468 distributed energy insiders, chosen because, because “they know what they are talking about,” Spokesperson Nicholas Rinaldi said.

The bulk of survey respondents (209 of 468) were from utilities, with 57% of those from investor-owned utilities, 18% from municipal utilities, 11% from retail electric providers, 9% from transmission system operators, and 5% from electric cooperatives. Other respondents included regulatory staff, policymakers and private sector DER providers.

The wide-ranging survey, which also touched on net metering and DER growth, delivered a number of insights. But Rinaldi highlighted one he said illustrates how difficult it will be for the sector to answer the four areas of concern with DER aggregation: Attitudes toward the sector’s readiness for the distributed energy transition.

When asked whether they felt the sector as a whole is prepared for a DER-heavy grid, 80% of respondents said no. Only 30%, however, said their own companies were not ready.

“There was a consensus but not a logical consensus,” Rinaldi said. “That essentially says, ‘there is a problem but it is not my problem.’”

Utility respondents are more consistent. They were three times more likely to say both the industry and their companies are not prepared, GTM noted.

Among utilities and DER providers reached for comment by Utility Dive, attitudes toward DER-readiness spanned the spectrum.

At one end was Duke Energy, the nation’s second-largest utility by customer base and an emerging leader in utility-scale solar.

“This issue isn’t on our radar,” Spokesperson Randy Wheeless said when asked about aggregation.

At the other end of the spectrum is EnerNOC, a leading demand response provider. Though the roles of utilities and DER providers “will vary by region and regulatory regime,” Senior Manager and DER Team Lead Jeff McAulay said, “there is a collective realization that DER have more value together than they do separately.”

In other words, some see a transformation coming and are preparing for it and some don't and aren't.

Even as his company has begun preparing, however, McAulay acknowledged that DER aggregation is new and it is not yet clear “which stakeholders can capture that value.”

Southern California Edison (SCE), which serves more than 14 million in the Golden State and has a DER aggregation pilot with SolarCity, was mid-spectrum. The transformation is coming, Director of Energy Policy Gary Stern said, but the distribution grid is not yet ready for it.

In particular, Stern does not yet see the technology in place to provide utilities with the visibility they need to manage DER and maintain reliability. “

We are working to modernize the grid so it can handle the proliferation of these resources,” he said. “We are not quite there yet but that is what we are trying to achieve.”

A data point from the survey expands on Stern’s point. In answer to the question of whether current efforts to value and monetize DER are sufficient, over 90% of the answers are “no.” Almost six in ten respondents say inadequate consensus among stakeholders on those and other questions is preventing progress.

The message is clear. The agreement now is that agreement is lacking. But embedded in the contention are crucial hints about the answer to the biggest question of all: Who will do the aggregating?

Agree to disagree: DER valuation

Distributed resources, especially rooftop solar, were seen just a few years ago the herald of a “utility death spiral.” Today, they figure highly in many utilities’ resource planning.

But if DERs are to be truly marketable as a grid resource comparable to conventional generation, their value must be defined. That’s difficult, since each type of DER, from solar to batteries and grid-enabled water heaters, offers different attributes from one another, and from traditional plants.

In states like California, Hawaii and Arizona, where DER proliferation is greatest, regulatory proceedings are already underway to answer that question, but most involve deep-seated disagreements between utilities and DER providers about valuation.

Whether DERs will be deployed as a merchant resource in electricity markets or used by utilities to create new revenue streams, the value question must be addressed, the GTM survey notes. At the very least, the diverse respondents appear to agree on the root of the problem.

When asked the greatest obstacle to DER valuation, 60% of respondents said the lack of consensus among stakeholders is the greatest hurdle to proper DER valuation. Among investor-owned utilities, the number was higher — 63%.

There is similarly broad agreement that the best way for regulators and policymakers to support utilities through the DER transition is with mechanisms that assign value to DER. Regulators (76%), private providers (67%), and utilities (49%) support regulatory and policy mechanisms that impose market-based reforms to deal with or assign value to DER, the survey reports.

“The numbers suggest that utilities, their regulators, and the private sector all want more of a role for the market and they are looking for regulators to provide that clarity,” Rinaldi said.

As utilities expand their distribution system resource planning, they will identify location specific needs where DER will be of value, said Avista Utilities Fellow Engineer Curt Kirkeby.

“The utility is in a unique position to leverage economies of scope as well as economies of scale that should incent investment and be competitive with third party aggregators,” he noted.

But there will also be an opportunity for DER providers, he added. “The value proposition for aggregators will be to deliver the same values the utility can at a lower price, or provide more value than the utility can deliver.”

From the survey and answers to Utility Dive queries, it is clear stakeholders are placing an increasing emphasis on the opportunity in DER aggregation.

“The market is already seeing utility movement,” the survey notes. Examples include Georgia Power’s recent launch of solar sales and installation services, Arizona and Hawaii utilities’ solar programs, and NextEra Energy’s investments in energy storage.

But the opportunity cannot be fully seized until the proper method of valuing DER is established, the survey reports. “The ability of utilities and private-sector service providers to bid into grid services markets relies on it, and the stakes are higher than ever for CEOs and decision-makers looking to develop profitable DER business models.”

DERs and electric reliability

“The challenges of accommodating a greater penetration of DERs on the grid are enormous and varied,” the survey reports. “There are issues of capacity shortfalls, ratepayer exposure, and finding the right business partner, to name a few.”

All these possible DER futures fuel the ongoing and unresolved debate over whether participation by DER providers might threaten reliability.

DER providers queried by Utility Dive are confident reliability is not at risk.

“Reliability will be managed through contractual means between the utility and the third-party aggregator,” EnerNOC Western Regulatory Affairs Director Mona Tierney-Lloyd said. “The third party aggregator should be able to put different resource characteristics together to meet the need, just like the utility could.”

Reliability would not be threatened if the right safeguards and economic incentives and dis-incentives are in place around DER performance, agreed Valery Miftakhov, founder of electric car charger company eMotorWerks.

“Aggregation services would and must be subject to contractual terms that dictate performance,” Avista’s Kirkeby agreed. “Reliability is still the responsibility of the utility. It must assess the quality of the aggregator’s portfolio and put appropriate mitigation measures in place, should the aggregator fail to perform. The utility would complete the same assessment if it was the aggregator.”

Franco Albi, manager of integrated resource planning at Portland General Electric (PGE), Oregon’s dominant electricity provider, told Utility Dive he is also confident.

“Everybody is going to protect reliability, regulators, the utility, and the providers,” he said.

PGE is, however, just beginning to develop DERs.

“As we learn more about the benefits to the distributed network, we are learning more about where we want them sited,” added Director of Customer Specialized Programs Bruce Barney. “As our distribution planning gets up to speed, we will have a lot more information available.”

SCE is deeper into the process and is concerned about an “information gap,” Stern told Utility Dive. “We need to coordinate what is happening on the distribution grid with what is happening on the transmission grid so we can insure reliability. We have been working with the California ISO for almost a year to make sure that information is accessible.”

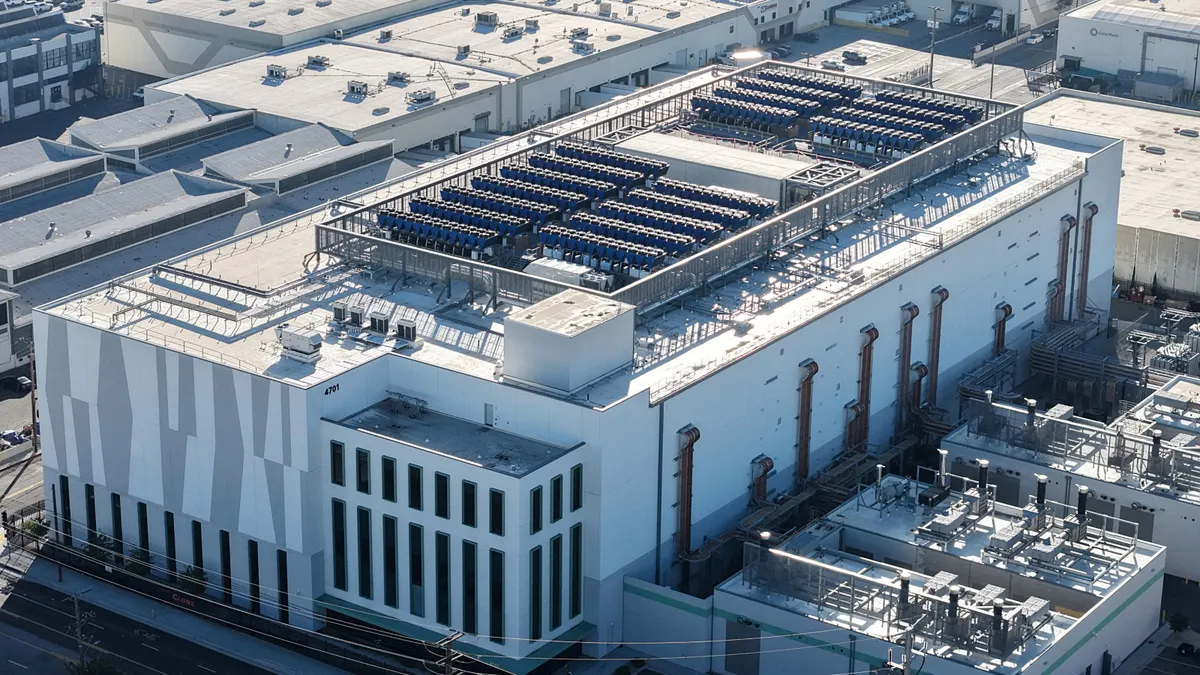

Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), California’s largest electricity provider, has pilot demand response programs and 1,700 MW of interconnected distributed solar, giving it some of the most experience with DERs among large utilities.

Even so, Mark Esguerra, head of electric asset management at PG&E, has some concerns.

“Leaving DER aggregation to the private sector, the utilities, or third parties, is not inherently threatening to system or local reliability DER aggregations do pose challenges to reliability,” he told Utility Dive.

But for safe, reliable, and cost-effective dispatch of aggregated DERs, there must be operational coordination and the appropriate levels of visibility, monitoring, and controls for the transmission system operator, the utility operating the distribution, and the DER aggregator, he said.

“The simultaneous response of multiple DERs on a single circuit from a single price signal may pose challenges to distribution reliability,” he stressed.

Utilities and DER: Anti-competitive?

To date, the private marketplace has been the main driver of DER growth, with developers targeting individual consumers for sales of rooftop solar, batteries, electric vehicle chargers, and the like.

With utilities beginning to see opportunity, a new debate has emerged regarding whether utilities should be able to compete with third-party DER providers to sell such products and services, either through their regulated businesses or unregulated subsidiaries. Given the utility’s existing customer relationship and access to usage data, many providers believe utility involvement in the DER space to be uncompetitive.

“Utility ownership of DERs does threaten the business model of developers like SolarCity,” EnerNoc’s McAulay said. “Grid operators should define the need and then allow aggregated DERs to bid in against other resources to meet that need.”

Utilities will not interfere with third party aggregators or the free market, SCE’s Stern insisted. “The information about the system necessary to them will be available.”

SCE is not arguing utilities have to be the aggregators, he added. California’s regulators have already approved the participation of third parties.

“We are asking for the appropriate-information sharing, not about market elements, prices, or deals, but about the physical activity of the resources so we can ensure the coordination between the distribution grid and the transmission grid,” he said.

Hawaiian Electric Company (HECO) agreements for aggregated DER will include “performance requirements and penalties similar to a contract with an independent power producer,” Spokesperson Darren Pai said.

There is no threat to the free market as long as utilities stay focused on their obligation to their customers, PG&E’s Esguerra agreed. Instead, collaboration between utilities and third parties will enable DER aggregation and associated technologies.

The big question: Who will aggregate DER?

While utility respondents felt comfortable ensuring that they would not stand in the way of DER growth, they and others could provide no such confidence in identifying who would be the primary entity to aggregate DERs, for one simple reason: No one seems to know.

Utilities will do the aggregation with cooperation from vendor partners, CPS Energy Sr. Manager Rick Luna told Utility Dive. CPS Energy is now successfully operating one of the first U.S. utility-owned distributed solar programs with cooperation from vendor partners.

Because of its existing customer relationships, the utility is “a trusted partner and looked to by customers for expertise in deploying new technologies,” Luna said. It is positioned to “leverage the value of DER in the market.”

These advantages and Esguerra’s concerns with reliability may suggest utilities will move into the DER aggregation themselves, but are waiting until technology maturity, market rules, and regulation are in place before moving more aggressively.

More than 20% of utility, regulatory, and DER respondents agree that between 6% and 20% of a traditional utility's revenue will come from renewables, storage, and resiliency services by 2021, according to the survey. About 20% more say those technologies could be as high as 35% of utility revenues by then.

But those revenues aren’t likely to come from DER aggregation services, many respondents agreed. A larger portion, including almost a third of utilities (30%), almost half of DER providers (46%), and over half of regulators (52%), expect DER providers to be the primary aggregator by 2021.

This is a particularly striking data point because so many of the key decisions will fall on the shoulders of regulators. Reinforcing it, 21% of utility respondents and 19% of DER provider respondents answered “I’m not sure” to the aggregation question, compared with 9% of regulators.

“Clearly, regulators see DER providers leading the charge into aggregation,” Rinaldi said.

“Although fully formed valuation mechanisms have yet to come to the market, third-party service providers are lining up to take advantage of the opportunity,” the survey reports.

California’s rules allow utilities, private sector vendors, and other entities to become aggregators, SCE’s Stern and PG&E’s Esguerra both noted.

“There is no specific advantage for either,” Stern added. “We envision a future in which utilities can offer the same services and have the same revenue opportunities that the market does.”

HECO has pending pilot programs in which the utility will administer private-sector demand response aggregators but the role, but impact of each on the market “is still not clear,” Pai said.

It is also not clear that utilities are up to compete in the market, he added. “Whether utilities or third parties can most effectively recruit customers and deliver the grid services achievable through aggregation will play out through the market and regulatory forces.”

DER providers believe all they need is adequate access to the proprietary data held by utilities.

“The utilities are, without a doubt, the entity who should be determining what the system need is and where it is and what types of ‘response’ could meet the need because no one else has the access to that information,” EnerNOC’s Tierney-Lloyd said.

But their determinations “should be vetted in an open process,” she added. “Ultimately, there has to be some criteria developed as to how decisions are made between competing options.”

Some DER management functions may have to end up under utility control, Miftakhov of eMotorWerks agreed. But private sector vendors are better positioned to be the primary aggregators because they have a “deep understanding” of DER owners’ technologies that utilities lack.

“For the utilities, these will remain only fringe resources economically for a long time,” he said.

Avista’s Kirkeby saw the same question from the opposite point of view. DERs “provide locational value for multiple uses that when stacked can derive much higher economic return,” he acknowledged. But without access to system information, aggregators “may not be able to realize the additional values that utilities can.”

If there’s one point of consensus among all respondents, it’s that the sector will have to learn by doing for a while.

“We would, as part of the process, provide the information to the transmission system operator and the aggregators,” SCE’s Stern said. “But we are just getting into the space. It is new. We anticipate being ready but we are still developing the information protocols that will help us insure reliability.”