Bipartisan infrastructure and Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, investments in carbon dioxide reduction can and must be used along with clean energy to address the climate crisis, the Department of Energy said in announcing its Carbon Negative Shot, or CNS.

But some clean energy advocates are skeptical of key technologies in DOE’s plan. CO2 capture and use or storage, or CCUS, of emissions from power generation facilities has underperformed and may protect fossil fuel generation and slow renewables deployment, and direct air capture and use or storage, known as DACUS, is almost untested, they said.

“Wind, solar, and batteries will continue to be enormously valuable, but they cannot decarbonize some major industries or take CO2 out of the atmosphere,” DOE Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary Dr. Jennifer Wilcox told Utility Dive. Technologies to do that need to be “at gigaton level by mid-century,” she added.

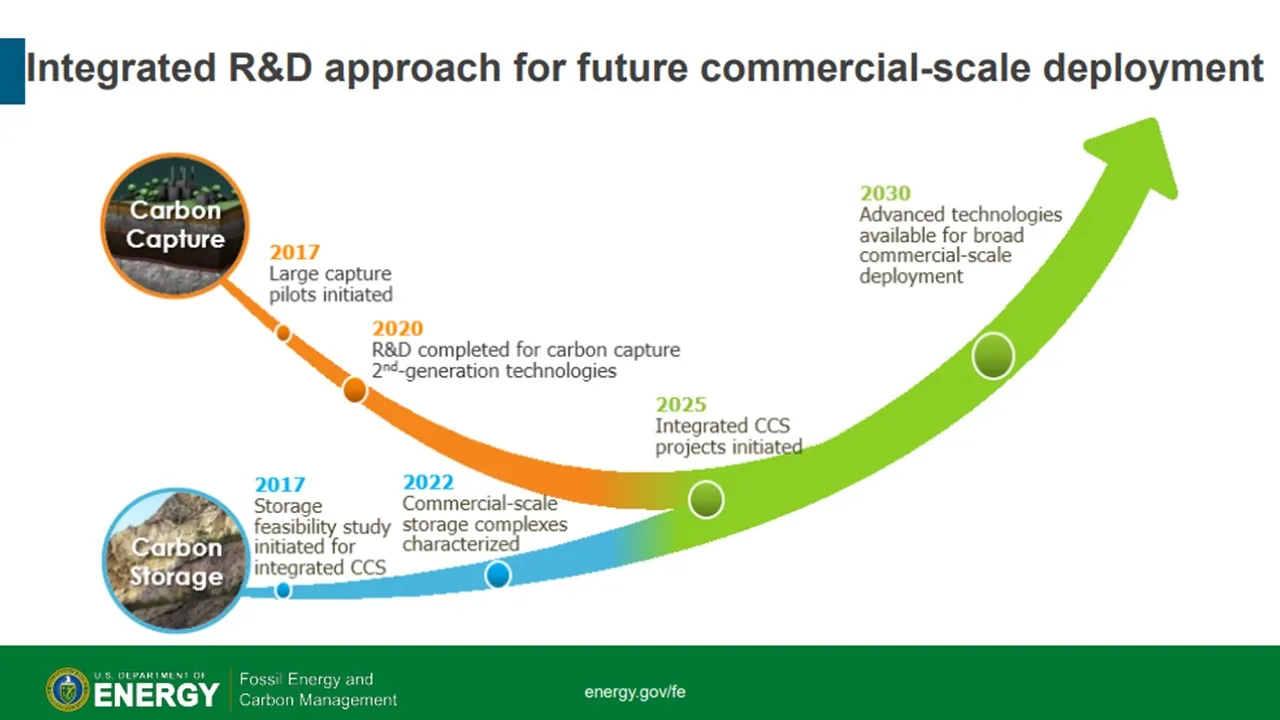

Few CCUS projects have proven fully “bankable” with current economics, the federal 45Q tax credit for CO2 reductions, and other revenues, DOE Loan Programs Office Director Jigar Shah told a July 20 CNS kickoff webinar. And history shows it takes $100 billion in public-private funding to get a technology to “full scale market acceptance,” he said.

All CO2 reduction options will be needed, policymakers, scientists, and clean energy advocates agreed in the webinar and interviews. Renewables growth is vital to decarbonization, and other pathways are also needed, webinar presenters added. But high costs and uncertain CO2 capture success leave clean energy advocates unable to endorse CCUS, they said.

DOE’s ‘Shot’

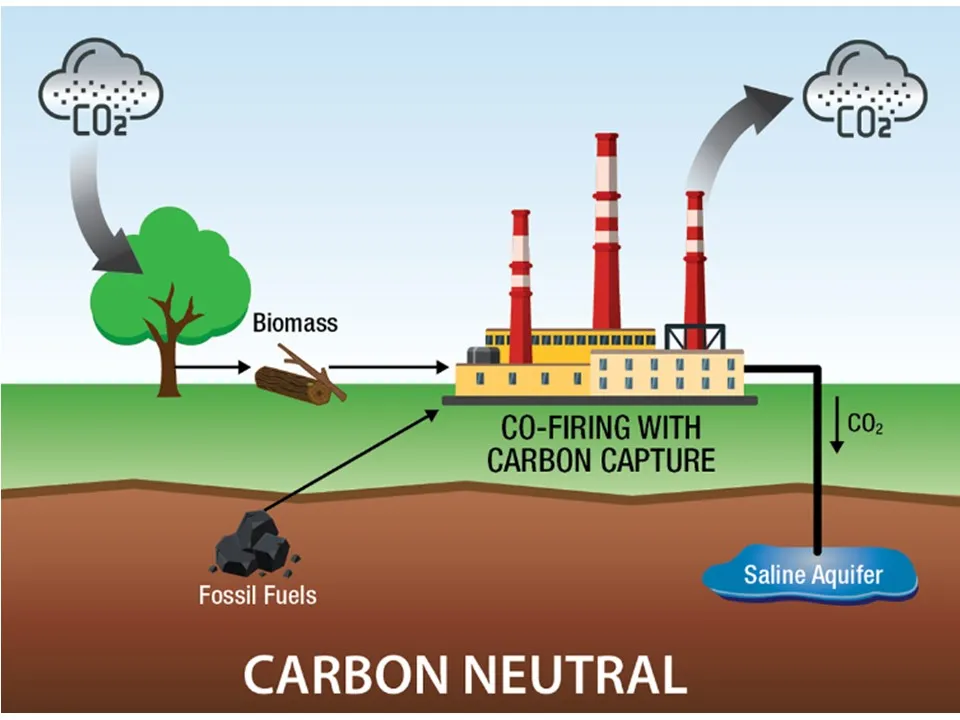

DOE’s “Shot” will only invest in CO2 reduction technologies that can drive the “gigaton-scale” cost to below $100 per metric ton, DOE Secretary Jennifer Granholm said in a November 2021 statement. Those include CCUS, DACUS, nature-based solutions to increase CO2 stored in oceans, soils, and forests, and biomass power generation, a DOE factsheet said.

There is over $12 billion for CO2 reduction in the 2022 Infrastructure law, according to Granholm, and a total of at least $99.6 billion for all the CO2 reduction programs in the IRA, a Senate summary showed. Early results from DOE’s plans are expected from CCUS while DACUS still must prove itself, webinar participants and clean energy advocates agreed.

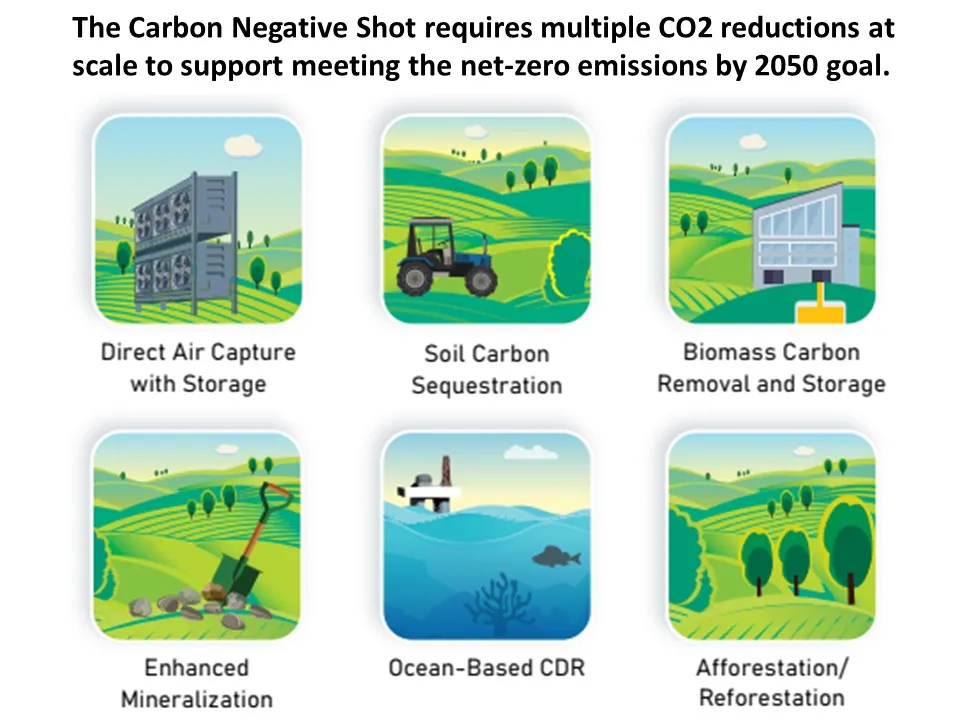

Direct air capture

Even with “unprecedented” clean energy growth, DACUS “will be essential” by mid-century, May 2019 Rhodium Group research concluded. But that will require significant research and development investments to make DACUS “ready for deployment when we need it most,” Rhodium added. And “current market opportunities and policy incentives” will not make DACUS cost-competitive, Rhodium reported.

The IRA’s federal 45Q tax credit increase rewards DAC with $180 per metric ton for CO2 storage and $130 per metric ton for CO2 use, according to the Carbon Capture Coalition. But DACUS needs $236 per metric ton to break even, Rhodium said. And to make it commercially viable, cumulative federal R&D spending to date of $11 million must average $240 million annually through 2030, it added, citing National Academies of Sciences research.

Once new technologies are deployed, though, “costs tend to come down,” a 2021 Industrial and Chemistry Engineering Research paper said. From solar’s earliest market entry, its cost fell “more than 100-fold,” and DACUS’s current cost in pilots of up to $600 per metric ton has a much shorter “reduction journey” to DOE’s $100 per metric ton goal, it added.

At $100 per metric ton, which a 2020 McKinsey study confirmed as market competitive, DACUS can attract private investment, finance new deployment and lead to further cost reductions, the researchers said.

But DACUS requires capturing CO2 from the air at concentrations now averaging just over 400 parts per million, or 0.04%, according to the McKinsey report. Much higher CO2 power plant concentrations, ranging from 5% for natural gas to 12% for coal, make them better suited for CO2 capture, according to Sierra Club Magazine Senior Editor Paul Rauber’s June 2022 research.

As a result, federal policies, programs, and incentives and private sector engagement have led to CCUS demonstration projects – and debate about its feasibility among scientists, environmentalists, and others.

The CCUS experience

Pumping gases into aging oil wells for enhanced oil recovery, or EOR, is proven technology, and oil industry payment for EOR, which also safely stores captured CO2, has supported success at recent CCUS demonstrations, DOE’s Wilcox said.

But the success of recent federally co-funded power plant demonstrations is questionable, according to the Sierra Club, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, and others.

NRG Energy’s Petra Nova coal plant in Texas, an early test of CCUS, operated from December 2016 to May 2020 and fully met its CO2 capture goals, NRG reported. The project’s economic viability, however, depended on returns from EOR, and CCUS operations were halted when oil prices fell during COVID, NRG acknowledged.

And the energy requirement for CO2 capture necessitated a separate natural gas plant without CCUS, which reduced NRG’s target 90% capture rate to 65.6% overall, according to independent academic research cited by Sierra Club’s Rauber.

SaskPower’s Saskatchewan, Canada, Boundary Dam power plant unit 3 CCUS system, in service since 2014, is the longest running and most successful CCUS project to date, both IEEFA and Sierra Club agreed. It came nearest the promised 90% CO2 capture rate and sustained its economic viability with EOR returns until 2021 technical problems forced it offline, they reported.

But the CCUS facility “resumed stable operations” in early 2022, SaskPower reported July 22. Though the yearly CO2 capture was down, due to the outages, Q2 2022’s capture was “well within SaskPower’s target range” and the system continues to capture and neutralize CO2 and other pollutants, it said.

This adds up to “an overall record of underperformance” and shows CCUS may not be a “good bet” for private sector investors, Sierra Club’s Rauber suggested to Utility Dive.

CCUS “is a big, complicated, expensive chemistry project on the back end of a very capital-intensive electricity-generating power plant,” IEEFA Energy Analyst Dennis Wamsted added. To drive the energy transition, “we need to close fossil fuel plants and build alternatives that don't have emissions.”

But claims about underperformance depend on how performance is calculated, DOE’s Wilcox responded. Petra Nova and Boundary Dam capture rates met design standards for the demonstration units and showed that DOE funding of new demonstrations can push the technologies to higher performances, she said.

But the cost-effectiveness of CCUS has also been questioned.

The CCUS cost question

Southern Company’s coal gasification and CO2 capture Kemper Project in Mississippi suspended operations in 2017 without significant CO2 capture, DOE reported. More importantly, equipment and other failures pushed its projected cost of under $3 billion to over $7.5 billion, IEEFA reported.

And Petra Nova and Boundary Dam could not remain financially viable without EOR revenues from a volatile oil market that increases oil production and new CO2 emissions, the IEEFA report added.

These cost questions make DOE cautious, Wilcox acknowledged. But “first-of-a-kind demonstrations will always be more costly,” and DOE will continue to co-fund capital investments with the private sector to prove new CO2 reduction technologies and drive “real movement down the cost curve,” she added.

That could be expensive, LPO’s Shah reminded the webinar. “To get to bankability and commercialization at scale will take that $100 billion investment,” which is one key reason potential private sector investors remain “tentative” about CCUS, he said.

IRA funding may help ease investor anxieties, Wilcox and others said. It increases the 45Q federal tax credit to $85 per metric ton for CCUS projects that store CO2 and $60 per metric ton for CCUS projects that use CO2, according to the Carbon Capture Coalition.

But models show the new 45Q benefits fall short of the up to $100 per metric ton needed to drive natural gas plant CCUS retrofits, DOE’s Wilcox said. They could, however, with other funding opportunities in the Bipartisan Infrastructure law and the IRA, accelerate deployments and “get us on the path to achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by mid-century,” she said.

CCUS advocates have long said that solar industry-like funding support “would bring the price down as it did for solar,” but that has not happened for CCUS, Sierra Club’s Rauber said. Higher 45Q values can now make CCUS “greatly more profitable,” and test its real potential, he acknowledged.

To reach that potential, CCUS will also need new deployments to answer questions that go beyond cost, webinar participants and clean energy advocates agreed.

More CCS questions

A multi-billion dollar private sector market “is developing,” but important questions remain unanswered, venture capital investor Lowercarbon Capital Partner and Head of Science Dr. Clea Kolster and other DOE webinar participants said.

CCUS could impose new land and water burdens, and both questions require more attention, DOE National Energy Technology Laboratory Director Dr. Brian Anderson said. Cost-effective storage at million-ton scale is in use, but it is critical to not minimize the potential uncertainties and risks at gigaton scale, he added.

“We have never done carbon storage at scale before,” IEEFA’s Wamsted agreed. “EOR has worked, but that does not mean it will work everywhere or for hundreds of years, and it could have significant human, environmental, and economic impacts,” he cautioned.

Land and resources for CO2 storage projects are available and there are ways to more rapidly make them accessible, witnesses to a July 27 Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works session said.

Smart-from-the-start land use planning, early community engagement, and streamlined permitting will improve land availability, The Nature Conservancy Director of U.S. Climate and Energy Policy Jason Albritton testified.

Environmental Protection Agency approval for more states of the “Class VI primacy” given to North Dakota in 2018 and Wyoming in 2020 will accelerate permitting for CO2 storage sites, Louisiana State Energy Office Department of Natural Resources, Technology Assessment Division Director M. Jason Lanclos, P.E., told the committee.

More permitting control for states with adequate environmental rules could safely accelerate land access, Lanclos said. And CCUS could help transition states dominated by conventional generation “to cleaner, more sustainable forms of energy,” he added.

But CCUS projects may lead to methane emissions, estimated to have a 25 times bigger impact on the climate crisis than CO2, IEEFA and Sierra Club said.

A July 13 DOE notice of intent to build six new CCUS demonstration projects at new or existing coal, natural gas, or industrial facilities is an example, IEEFA reported August 1. The demonstrations’ lifecycle CO2 emissions will be monitored, according to the notice. But coal mine, natural gas pipeline, and storage methane leaks could significantly compromise projected benefits, IEEFA modeling showed.

DOE’s Shot will fund advances in “proper monitoring, reporting and verification” of all emissions, Wilcox responded. A key goal “is to make sure upstream and midstream sources are as leak tight as possible, and the first step is identifying where the leaks are and quantifying them,” she added.

The moral hazard

CCUS is a solution “everybody can love, including fossil fuel companies that can continue producing CO2 and claim it will be captured,” but there is “a moral hazard in assuming it will be feasible,” Sierra Club’s Rauber said.

Sierra Club policy acknowledges clean energy alone is “inadequate,” but R&D efforts must not prolong the use of fossil fuels, he added.

“R&D to reach net zero emissions in 2050 makes sense,” but this decade’s focus has to be on renewables growth, IEEFA’s Wamsted agreed. CCUS technology “is not yet proven, and it might be more cost-effective to replace fossil fuel plants with renewables,” he said.

But there is another hazard, DOE’s Wilcox cautioned. Power plants, industry, transportation, and agriculture “will continue emitting greenhouse gases, and will continue leaking methane,” she said. Even though CO2 reductions largely “do not exist at scale yet,” they “can be in the toolkit in a decade if we invest today.”