The following is a contributed article by Malayah Redmond, an associate for the Ceres Company Network, a unit within the sustainability nonprofit Ceres.

The urgency to shift to a low-carbon economy grows with each passing week, as the climate crisis bears down on communities all over the world and as the economic opportunities of climate action continue to skyrocket.

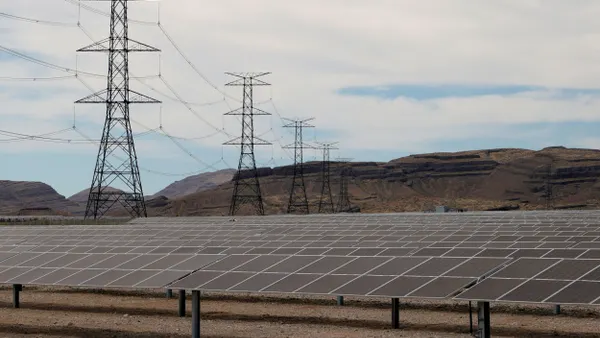

Companies are responding, pledging in droves to shift their energy sources to renewable supplies, which, in turn, is spurring the rapid expansion of renewable energy projects. But as developers, investors and energy buyers and producers compete in this burgeoning industry, it’s imperative they don’t make things worse for the very communities already enduring the brunt of climate disasters. In project planning, minerals extraction, construction and operation, these stakeholders must respect the rights of local indigenous groups, workers and other affected communities to ensure the creation of a just and sustainable future for all.

Increased demand for energy sources

Over the past five years, some of the largest companies and investors from around the globe have committed to switching to clean energy use, with over 340 companies officially pledging to source 100% of their electricity from renewable sources, according to RE100’s annual report.

Developing renewable energy resources delivers vast benefits, including creating good-paying, stable jobs, slashing greenhouse gas emissions, improving air quality, and gaining access to reliable energy sources. But the ramp-up in clean energy production also comes with risks across the whole of the renewable energy value chain.

Effects on salient environmental and human rights risks

From 2010 to September 2020, the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, or BHRRC, collected over 2,300 allegations of human rights abuses occurring in various stages of the renewable energy value chain in Latin America, ranging from mining to construction. These risks include land rights violations, community displacement, indigenous rights violations, harassment of human rights defenders, and, occasionally, violence and threats against local communities.

One particularly critical risk stems from the rising demand for minerals used in the production of solar panels, as mineral mining has historically been fraught with human rights abuses. The Resource Centre’s research finds that many renewable energy companies’ human rights due diligence processes are not keeping pace with expanding extraction.

The following list provides a sample of human rights risks across the renewable energy value chain identified by BHRRC:

|

Risk |

Definition |

Prominence in Value Chain |

|

Labor Rights, Health and Safety |

Living wage, worker health and safety, gender wage equality |

Production, Development, Operations |

|

Environmental and Human Rights Defenders (HRD) |

Commitment to respect the rights of human rights and environmental defenders, including policies committing to non-retaliation |

Production, Development, Operations |

|

Indigenous Peoples’ and Affected Communities’ Rights |

Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) and the right to self-determination Recognition and respect for all ways of life, customs, traditions, government and land |

Development |

|

Land Rights |

Right to land and natural resources therein whether individually or collectively, including through the identification of legitimate landowners and the application of a just and fair relocation policy |

Production, Development |

|

Right to a Healthy and Clean Environment |

The right to a low-carbon economy, including public environmental impact assessments, life cycle assessment on technologies, raw materials sourcing and waste generation |

Production, Development |

Challenges to mitigation and prevention

The risks to people’s environmental and human rights are pervasive and touch multiple parts of the renewable energy value chain. To discuss these salient risks, challenges to mitigation and prevention and opportunities to improve conditions for people affected as the transition to a low carbon economy unfolds, Ceres, in collaboration with BHRRC and the Principles for Responsible Investment, brought together key stakeholders from across the renewable energy value chain.

The stakeholders agreed that in the production phase of new renewable energy projects, developers should identify possible harmful environmental health and economic impacts on local communities at the sites of materials extraction. Common ones include chemicals exposure and limited access to potable water and healthy soil. For stakeholders whose direct range of influence is limited, such as corporate buyers and investors, such challenges might not be transparent.

In the development phase, stakeholders should be vigilant about any signs of modern slavery, especially through the use of migrant labor for construction and threats to the lives and physical safety of environmental and human rights defenders. It requires that corporations and investors have a full understanding of the context of the communities and environment in which renewable energy projects are being built.

In the operations phase, establishing equitable and just labor contracts and responding to systemic threats to stable and affordable community access to energy supplies are key issues. Stakeholders should establish effective due diligence processes and mechanisms to prevent risks on an ongoing basis.

Jessie Cato, natural resources and human rights program manager at BHRRC, described why these challenges must be solved and the fear of what would happen if they are not: “Like any new and growing sector, there is a small time to influence how the sector will operate and if we do not push for human rights to be a central part of this, if we accept a transition that is fast, but not fair, we risk not only allowing abuse to flourish unchecked, but that abuse will become part of the business practices of the transition.”

Taking action

To ensure greater respect for people’s environmental and human rights in renewable energy development, investors, buyers, developers and civil society groups involved in the renewable energy value chain should:

- Engage with all stakeholder groups across the value chain to develop best practices to address salient environmental and human rights impacts. All parties should maintain open lines of communication and constructive relationships with impacted rightsholders through ongoing engagement with local communities.

- Collaborate on mutually agreed-upon human rights due diligence mechanisms, particularly where there are shared value chains or overlapping operational geographies, to help drive consistent action toward the protection of environmental and human rights.

- Increase demand for renewable energy projects that uphold all environmental and social considerations through long-term contracts that include strong due diligence mechanisms and respect for environmental and human rights. This includes but is not limited to procurement, labor and operational contracts.

- Level set and share supplier and business partnership policies and case studies publicly, when possible, to increase transparency, accountability and stakeholder trust. Identifying success stories across the value chain creates an opportunity to learn and reflect upon best practices moving forward.

- Engage and align with asset managers and rating agencies to develop human rights performance and due diligence criteria to integrate into investment-decision making.

- Disclose evaluated environmental and social impacts for renewable energy investments on an annual basis. Renewable energy buyers and investors should encourage the same level of disclosure from renewable energy companies and developers.

Collaboration among key stakeholder groups including impacted communities is key to building the foundation for a just transition to a low-carbon economy. Now is the time to lift the voices of these communities and workers in the decision-making process and learn from their vast experience and knowledge to truly establish a just and sustainable world.