Dive Brief:

- The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission has certified NuScale Power’s small modular reactor design, the first of its type to win federal approval. It’s the seventh reactor design cleared in the U.S., according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

- Regulations published Jan. 19 in the Federal Register allow applicants or licensees to build and operate a NuScale standard design. The final rule is effective Feb. 21.

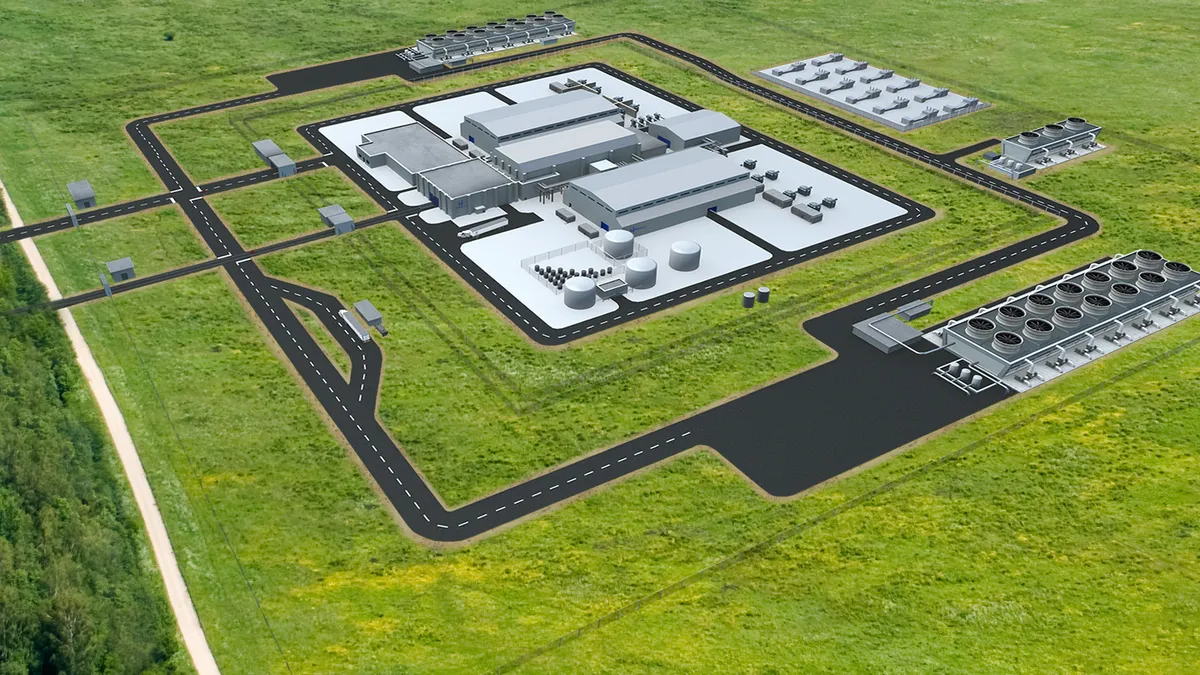

- The design is an advanced light-water SMR with each power module able to generate 50 MW. NuScale’s VOYGR SMR plant can house up to 12 factory-built power modules, about one-third the size of a traditional large-scale reactor, according to the DOE. The NRC accepted NuScale’s SMR design certification application in March 2018 and issued its final technical review in August 2020.

Dive Insight:

Diane Hughes, vice-president of marketing and communications at NuScale, said in a statement NRC’s approval makes the company’s VOYGR power plant a “near-term deployable solution.”

DOE is working with Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems, or UAMPS, and the Carbon Free Power Project to demonstrate a six-module NuScale VOYGR plant at Idaho National Laboratory. The first module in its 77 MW reactor design, which has not been approved yet, is expected to be operational by 2029 with the whole plant in operation the following year, DOE said.

The industry and its advocates say SMRs can play an important role in decarbonizing energy. Unlike large-scale nuclear plants, SMRs, which are defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency as advanced nuclear reactors with a capacity of up to 300 MW, are modular units made in factories and transported to a site for installation.

With the NRC’s certification of the NuScale design, “SMRs are no longer an abstract concept,” Kathryn Huff, assistant secretary for nuclear energy, said in a statement.

Critics say SMRs have a history of significant cost overruns and schedule delays. And they link their opposition to SMRs to longstanding criticism of nuclear energy as dangerously vulnerable to earthquakes, terrorists, reactor leaks and other hazards.

Marc Bianchi, an analyst at Cowen Equity Research, warned in a Jan. 4 client note of “some risk around the [UAMPS] project in early 2023 as the project cost appears to be running above a key threshold” of $58/MWh. He said the rising costs give UAMPS members an option to exit the project.

“The costs have reportedly increased to $80-$100/MWh driven by materials inflation and higher interest rates,” Bianchi said. “While on the surface a 50% cost increase would seem highly problematic, commentary from municipality meetings suggest they remain committed to the project given [the] limited availability and high cost of alternative around the clock clean power options. We expect to know more in the coming weeks.”

The Carbon Free Power Project earlier this month reaffirmed its commitment to NuScale’s SMR with a new budget and finance plan. It also accepted an update to a cost reimbursement agreement and cost estimate that “further refines the anticipated total cost of the project.”

“Energy projects nationwide are facing external impacts including inflationary pressures on the energy supply chain that have not been seen for more than 40 years,” Hughes said in a statement.

The project is cost-competitive and higher costs “reflect the changing financial landscape for the development of energy projects nationwide,” she said.

Scott Williams, nuclear policy analyst at HEAL Utah, which has opposed the SMR project, said in November that the last chance for project participants to quit is probably in 2024, depending on the NRC’s review.

David Schlissel, director of resource planning analysis at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, said the higher costs “make it even more imperative” for UAMPS and participating utilities and communities to seek information about other energy resources that can provide the same power and reliability as the SMR but at lower cost and less financial risk.

“History shows that this won’t be the last cost increase for the SMR project,” he said.

Naomi Oreskes, a professor of the history of science at Harvard University, said during an online presentation Monday the federal government has not played a leading role in SMR design, which could have helped reduce costs.

As policymakers seek energy technologies that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, nuclear power is attractive because it can supply large amounts of energy, Oreskes said.

“That part of the claim is true,” she said “But the problem is we can’t do it fast enough and we can’t afford to wait another 20 or 30 years for the SMR idea to get sorted out,” she said.

NuScale submitted on Jan. 1 a second standard design approval application for its updated SMR design based on a six-module VOYGR-6 power plant configuration powered by an uprated 250 MWt, or 77 MWe, module.