A new solar sector is emerging, a sector so new that its name — community shared solar — has not yet been precisely defined.

That is why the Department of Energy (DOE) SunShot Initiative just gave $14 million to 15 awardees to define what community shared solar is, identify what business models will work, and explain how it will make solar more accessible and affordable. Only one thing is now clear.

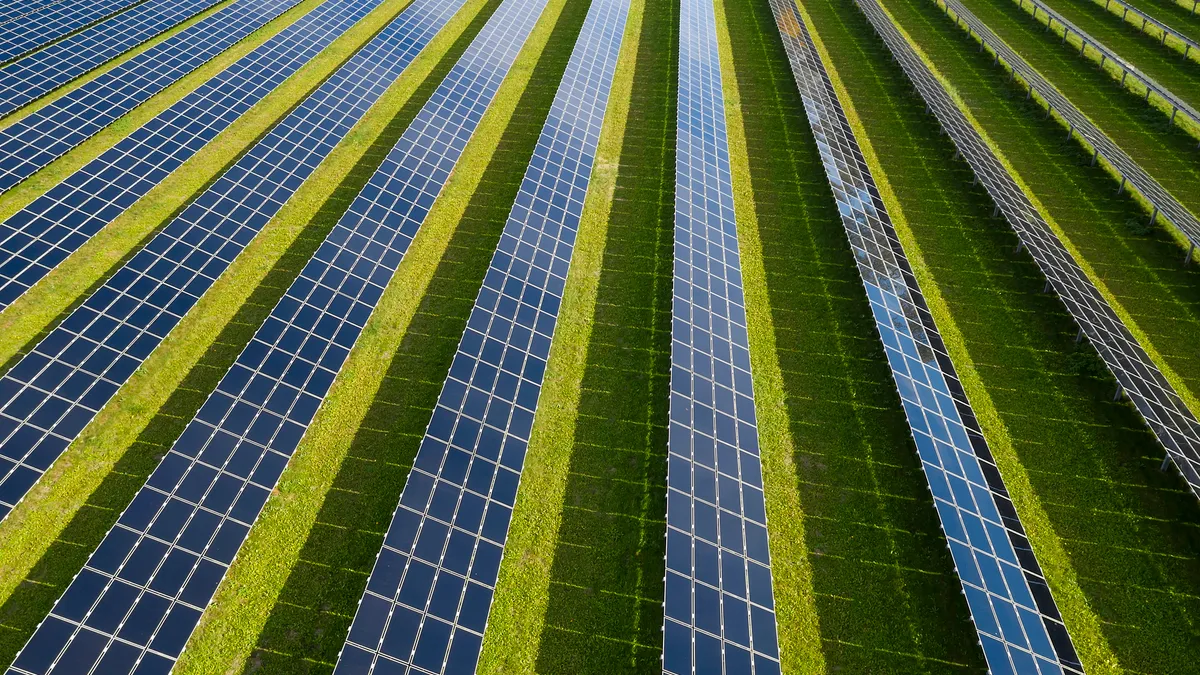

“There is no dispute that installing solar on a roof is far less economically efficient than putting 5,000 panels in an open field in 60 days and selling it to 1,000 customers,” said Paul Spencer, founder and president of Clean Energy Collective, the biggest U.S. community solar developer. “There is no comparison as to the capital efficiency of those two solutions.”

In terms of accessibility, explained SunShot Director Minh Le, a new analysis from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory now in peer-review suggests that “between 50% and 75% of households and just over 50% of businesses are unsuitable to host PV systems on their roofs because of shade, orientation, structural factors, or ownership issues.” The new sector will bring solar to them.

As for affordability, community shared solar can reduce solar costs in two ways and both are attracting significant utility interest.

“Utility participation is going to be transformational,” Le said. “The perceived resistance to solar from utilities is really not there when you talk about aggregating consumers on larger projects to get economies of scale and siting near substations or distribution feeders to reduce interconnection issues.”

DOE gets into community shared solar

DOE’s role in the current expansion began in 2012 with its report, "Guide to Community Shared Solar: Utility, Private, and Nonprot Project Development," Le said. The Guide outlined business models, challenges, and opportunities. It led to 2013’s “Community Shared Solar: Getting to Scale" workshop.

The workshop developed DOE’s expansive definition that includes a range of ownership concepts and benefit allocations. Interest from utilities, the solar industry, and other stakeholders in breaking down barriers to community shared solar led to SunShot’s Solar Market Pathways program.

The current round of Market Pathways funding awarded the Solar Electric Power Association $705,830 to study “the intersection of community solar business models and consumer demographics” and produce “more standardized, streamlined and cost-effective business models.”

“One of our first tasks,” explained SEPA Senior Research Manager Becky Campbell, “will be to find some level of consensus about how these programs are defined.”

Campbell hopes SEPA’s survey and research will develop individual business models with unique names so “we can not only be on the same page when discussing community solar, but we can take it one step further and start to use common terminology to describe the traits of each program model.”

The commercial business models

CEC is the only private sector community solar developer offering both established business models, according to Spencer.

In one, customers own panels. “The customer makes a down payment on the panel at the front end of the transaction, with cash or financing, and owns the asset,” Spencer explained. “The customer gets 100% of the power being sold to the utility in the form of a dollar amount credited to their utility bill for the production of the solar-generated electricity produced by the customer’s panels in the array.”

The dollar amount credited is slightly less than the amount earned by the total output of the panels owned because a small percentage goes into a CEC-administered escrow account to cover operations and maintenance and other expenses.

CEC’s Remote Meter proprietary billing software is merged into the local utility’s billing system. It automatically integrates the credits earned by the solar with the customer’s utility bill so that the customer gets one utility bill.

The panel investment can eventually pay for itself, creating ownership equity. CEC earns its money by selling the array’s panels at a slight mark-up from cost.

“The second model, a rental model, is more complicated to understand but less complicated for us to do, which is why other companies are doing it,” Spencer said.

CEC calls its rental model SolarPerks. Other players like SunShare and SunEdison also use it. It provides a net utility bill savings proportional to the amount of kilowatt-hours the subscriber commits to paying for but the subscriber has no upfront cost and earns no ownership equity. A residential customer gets a guaranteed 5% savings while commercial customers can save up to 10% or more.

The subscriber deals with two bills. The utility bill shows the dollar amount of the credit for 100% of the solar kilowatt-hours to which a residential subscriber commits. CEC debits that subscriber’s bank account for 95% of the credit.

“Though there is a monthly savings, the subscriber has no ownership,” Spencer stressed. “It appeals to a different public and works differently, but still saves money.”

Utilities have been less successful with the ownership model than with the rental model unless, like CEC, they offer some form of loan or on-bill financing to help customers with upfront costs.

“If you finance and blur the lines, the first model ends up looking a lot like the second model until the panels are paid off,” Spencer said. “But the market definitely likes the zero-down option and since it supports more solar, it produces more environmental benefits.”

DOE awards

CEC won a $700,000 SunShot Initiative award last fall to develop and implement the National Community Solar Platform (NCSP). It is intended to help developers, EPCs, utilities, and community solar organizers avoid the complexities that CEC had to resolve with securities law, tax law, electronic on-bill crediting solutions, state and federal law, and land use issues to become the leading U.S. community solar developer.

Expected to launch by spring 2016, the platform will provide web-based access to information and market-proven tools that will make community solar development “easier, cheaper, faster, and widely scalable.”

A Market Pathways award of $2,430,682 went to Dominion Virginia/Virginia Electric and Power to lead a team of representatives from state government, research institutions, environmental organizations, local communities, and solar businesses in developing business models for utility-administered solar.

Given the lethargy of Virginia’s solar market, Dominion Virginia’s interest is groundbreaking. And given that a similar coalition of stakeholders teamed with Duke Energy in nearby South Carolina to prepare the ground for what may be a coming solar market explosion there, the progress of Dominion Virginia’s team will be worth watching.

Market Pathways awarded $1,238,308 to the Cook County Department of Environmental Control’s Chicago project to identify business models that most benefit seniors, multi-unit housing tenants, and low-income customers. “By having the solar project in the community instead of buying solar generated electricity from a distant utility-scale project, it also offers the opportunity for local economic development,” Minh said.

How big can community shared solar get?

When world-leading solar developer First Solar became “a minority yet significant owner in CEC” late last year, Spencer said, the companies calculated that if only about a quarter of all roofs are suitable for solar and 40% of those are occupied by renters, the market for community solar is about seven times as big as that for rooftop solar.

“We share First Solar’s enthusiasm about the opportunity,” Minh said. “Our projection is that between 20015 and 2020 there will be a cumulative $6 billion to $12 billion invested in the community shared solar space – but that is an estimate made in the very early days of what could be a very exciting market.”