Utility sector investment in energy storage is poised to grow, especially if regulatory barriers can be lowered, according to an analysis of the results of Utility Dive’s 2016 State of the Electric Utility Survey.

For the second year in a row, energy storage ranked first among the technologies for future investment among the utility executives responding to the survey.

A total of 65% of utility respondents named energy storage as one of three emerging technologies in which they should invest more, compared 52% who said they should invest more in distributed generation as one of the three options. Utility scale solar and wind power was ranked third in terms of target investment among the executives, with 47% choosing it.

Those results reflect findings from the 2015 Utility Dive report. In last year's survey, 53% of utilities named energy storage as one of the top three technologies for future investment, giving it the clear lead over all other technologies.

“We are seeing a lot of interest in energy storage from integrated utilities because they have the ability to see across the whole market” from generation and transmission to distribution, Brian Perusse, vice president of international market development for AES Energy Storage, said.

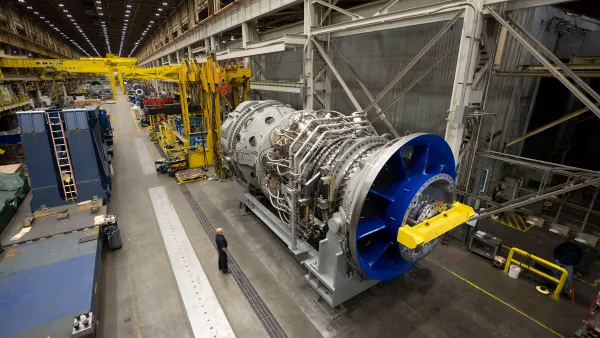

Interest in storage is also underscored by the fact that it is an alternative to several asset classes, he said, explaining that it can be an alternative to a peaking plant or to a pumped hydro plant or, like a transformer, it can show up anywhere on the grid.

A total of 515 U.S. utility professionals responded to the survey. While the respondents came from every region of the country, the highest response rates were from the Midwest and the Pacific Coast where the size and population of those regions largely account for the higher number of responses.

The majority of respondents — 61% — are employed by investor-owned utilities, with responses from municipal utilities, electric cooperatives and public power agencies each accounting for between 15% and 10% of the remaining responses.

The survey showed that most utilities have accepted that the utility business model has changed and are now more concerned about what shape the 21st century utility will take.

For instance, many utilities are already invested in energy storage according to the survey, but it ranked about midway in the responses to a question about current investments, with 22% of the respondents saying they most invested in energy storage, compared with 66% who said they were most invested in utility scale wind and solar power and 64% who reported they were most invested in demand-side management.

Drivers of storage's popularity

The importance energy storage will play going forward with utility executives was underscored by the fact that 32% of respondents said integrating variable renewable and distributed resources into their grid was their top concern with respect to their changing power mix. That was followed closely, at 31%, by concerns about minimizing the cost of those changes for customers.

Those concerns point to one of the factors that could drive wider adoption of energy storage. Integration of emerging technologies, in fact, was also listed as the greatest obstacle to the evolution of the utility business model as a whole by 21% of the respondents, ranking just behind the exsisting regulatory model, which garnered 35% of the votes.

Combining those concerns with the fact that 66% of respondents said they are looking at offering energy management and efficiency services to customers to open up new revenues streams could give a glimpse at how utilities would prefer to invest in energy storage.

The survey also shows that when they do invest in distributed resources like storage, they want the option of rate-basing the investment.

When asked to identify various strategies they think their utility should use to build a business model around DERs, 59% of respondents said they should deploy them through rate-based investments as a regulated utility. That was just under the 60% of respondents who said they should built a DER business by partnering with third-party providers, and many respondents chose both options.

All told, 65% of the respondents said they should be able to own and rate base DER investments under any circumstances, 17% said they should be able to, but only in "specific instances wehre the comptitive market fails to deploy DERs that would benefit the grid." 12% supported utility DER ownership through only unregulated subsidiaries, and 6% said they should not own DERs under any circumstances.

The takeaway is that utilities see value in energy storage and other DERs but are still struggling to come up with a business model that would make storage commercially viable.

“Under existing regulatory regimes a utility is most likely to ratebase an energy storage investment, if they can,” Anissa Dehamna, principal research analyst for energy storage at Navigant Research, said.

Storage in the field

Many of the findings on storage investment patterns and appeal to utilities are on display in current power sector projects.

Electric Transmission Texas LLC, a joint venture of American Electric Power and Berkshire Hathaway Energy, installed a installed a 4-MW battery in Presidio, Texas, as part of a transmission reliability solution and paid for it using Texas’ transmission cost of service regime.

In that case, regulators could view the battery system much like they would a transformer or any other piece of transmission equipment, but the use-case for storage is not always so straightforward.

AES Storage built a 20-MW battery project for a 544-MW power plant owned by its affiliate, AES Gener, in Chile. That project was structured to conform to the regulatory regime in Chile where power plants are obliged to set aside capacity to provide frequency regulation service. The battery storage system was able to provide frequency regulation to the grid, but it also freed up capacity at the generating plant, allowing it to boost output and sell spinning reserve services in a market with high energy prices.

The point is that storage is only useful in the right context, and that changes on a case by case basis.

“Broadly speaking, to facilitate greater investment, storage should not be pigeon holed but should be viewed as an asset that can be used as generation, transmission, or distribution,” Dehamna says.

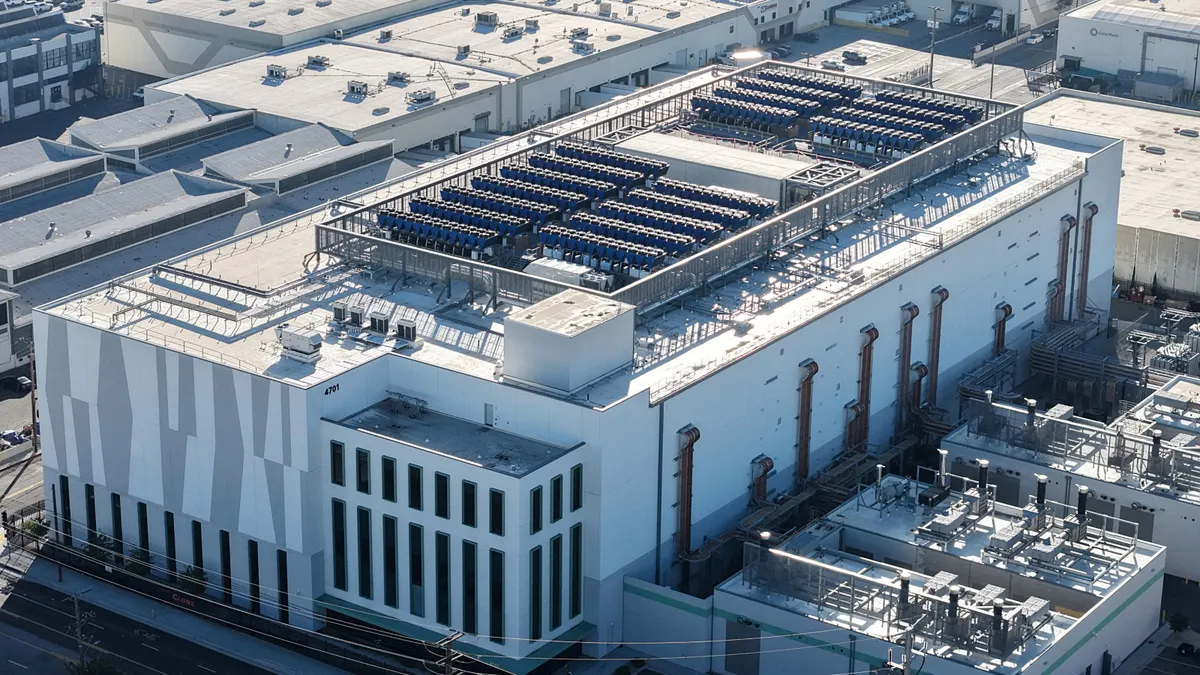

In California, the regulatory regime allows energy storage projects to be deployed as either rate-based investments or as third-party projects.

“Typically, the form of investment is correlated to the use-case application,” Gary Stern, director of energy policy at Southern California Edison, told Utility Dive.

An energy storage project is deployed primarily for distribution grid reliability may be better suited as a ratebased asset, Stern said, while a storage project that is primarily providing energy market services, such as resource adequacy capacity or energy price arbitrage, may be better suited as a third-party owned asset providing services to the utility.

That perspective on storage use cases echoes what his SCE colleague Mark Irwin told attendees at DistribuTECH 2016 last month in Orlando — that the distribution-level storage contracts were all for third-party owned projects and SCE is focusing its utility-owned storage efforts on larger-scale offerings since the RFO process can take too long for distribution circuit needs.

Making storage cost-effective, even in states like California with high electricity prices, usually involves “stacking” the benefits of storage — allowing a battery deployed for reliability purposes to provide grid services when not being used by the customer, for example.

But according to Irwin, SCE can’t perform those market functions with the batteries it has on the distribution system because “we do not yet have the communication and control capabilities in place.”

Typically, using storage for multiple functions means that an operator must know when it is in use for its primary function — such as backup power — and when its capacity can be used for grid services. When the end user is the one bidding the storage into the open market, as can be the case with some third-party owned systems, visibility is less of an issue. But, if a utility wants to use the batteries that provide backup power to a given facility for grid services, it must first be able to tell if it is in use for its primary function first.

To solve that problem, SCE announced last month it would invest $2.5 billion to upgrade its distribution grid and implement a grid management "system of systems" that can both give greater visibility and control DERs at the end of the grid.

“We still have a ways to go there,” Irwin said. “It will be a number of years, but that’s our vision.”