The potential of energy storage has never been higher than it is today. As intermittent renewables like solar and wind get integrated onto the grid, storage is seen as the Holy Grail. No longer does electricity have to be consumed as it is generated; it can be stored for later.

But the potential has always been there—the technology has not. Signs are that’s starting to change, and some of the industry execs I’ve spoken to say they believe the storage market will rise to prominence in the next 5-10 years.

Electric utilities scoffed at rooftop solar five years ago and today rooftop solar is arguably the most disruptive challenge that utilities face. Most utilities are dismissive of energy storage today, they warn, just like they were with solar five years ago.

I spoke to Greg Miller, executive vice president of market development for energy storage company Ice Energy, about the future of the U.S. energy storage market at Distributech 2014.

“The stars are aligning," Miller said, but challenges still remain.

Business models

Ice Energy was founded in 2003, which is practically ancient for an energy storage company.

Their technology has been in the market since 2004, said Miller, and it’s the non-tech side of the business that the company has been building out since then.

“We went from piloting to megawatt-scale with munis. Now we’re doing small pilots with utilities that are maturing with the mandates to go to utility-scale,” Miller said. “When you go to scale, you have to have that part of your business model well thought out and implemented. You have to have the customer contracts that you can repeat from door to door to door to door. That’s what we’ve been developing for the last 5-6 years. It’s the business models, and it’s the way you approach the customer.”

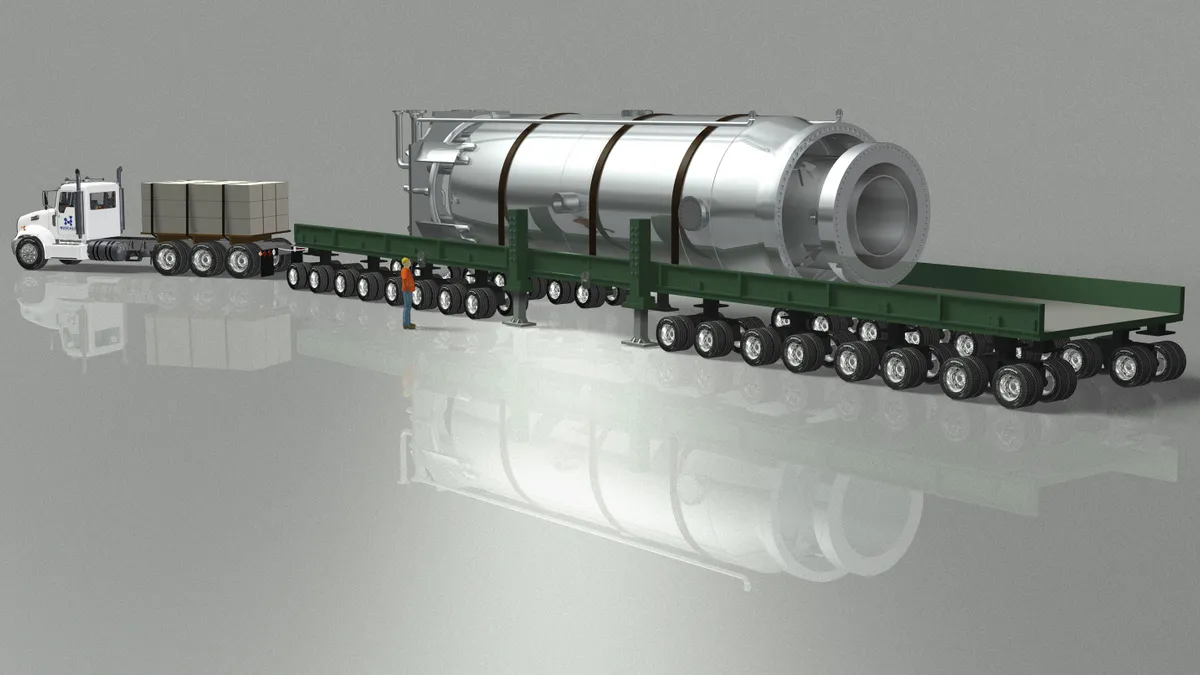

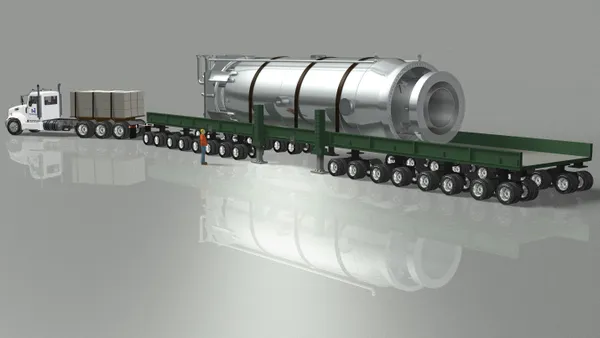

Ice Energy’s model is an interesting one. The company’s Ice Bears use “common, off-the-shelf components in the air conditioning industry to make ice” and connect directly to air conditioners in the commercial and industrial space.

The Ice Bears “charge” during low load times and use the “fully charged” ice block, which consumed energy the night before, to deliver up to six hours of cooling during the daytime.

The Ice Bears can also deliver demand response, which Miller says gets their business model “over the edge.”

Demand response payments of $250/year are “not enough money to get anybody excited,” Miller said. But “to get customers interested in a utility energy storage asset, and to have them be willing to shut their power off in some of their loads for 30-40 hours a year, you’re going to have to give them something.”

“Our spin is we’re going to give them a $10,000 air conditioner asset and take that off their budget,” Miller said, noting that the air conditioner replacement comes out of the utility’s energy efficiency budget.

As the energy storage market moves to grid-scale deployment, Miller believes storage companies that have experience and tried-and-true business models will have an advantage over the younger upstarts in the market.

Policy and regulation

Last year, the California Public Utilities Commission (PUC) issued a historic ruling requiring the state’s investor-owned utilities to have a certain amount of energy storage. The mandate essentially guarantees a market for energy storage, but “the mandates aren’t that big compared to what the utilities' business investments are,” Miller noted.

“What I’m learning is that the PUC is learning,” Miller continued. “They are learning cost, cost evaluations, competitiveness, is the market ready, are the companies ready, are they manufacturing. Without those drivers, none of that gets exposed. I see the PUC saying, let’s walk before we run.”

Energy storage today is, to a significant extent, a policy-driven market. That’s not to say that a high penetration of storage won’t happen without friendly policies, but it won’t happen anywhere near as fast.

“I think the electric utility industry really requires… I don’t want to say mandates, but some direction,” Miller said. “Like renewables, utilities wouldn’t be using storage unless there was driving force behind it.”

In that sense, California is leading the way by showing other state regulators and policymakers what works and what doesn’t when it comes to deploying energy storage at grid-scale.

Emerging markets

Besides California, where will see new and emerging markets for energy storage?

Miller believes markets will inevitably pop up in places “where renewables are getting a high level of penetration.”

Energy storage, he said, makes the most sense for island power: The Bahamas, Aruba, and Puerto Rico, which recently issued its own energy storage mandate.

Next might be the Northeast. The cost of infrastructure there is much higher, Miller said, and the infrastructure is much older. Storage can be deployed at grid-scale to defer a utility’s capital spending on replacing or building new infrastructure.

“And I don’t know why Texas, New Mexico and Arizona aren’t the next,” Miller added. “Their infrastructure is ailing, and that will expose problems when the growth and temperature hit the point where you start seeing outages.”

That’s when “utilities will get back again to investing in their infrastructure,” he said, but they “don’t want to spend a lot while their load growth is at 0.15% per year.”

Miller thinks that adoption of energy storage will happen faster abroad. “The U.S. is very fortunate—we have a very good grid—so our market is going to be the slowest,” he said. “It’s just going to be slow.”