Sometime soon, President Donald Trump is expected to sign legislation that will allow internet providers to sell valuable pieces of your online history to third-party providers and advertisers. Balanced against privacy concerns are arguments that the current rules are stifling innovation.

It's a relatively wonky debate. But in a sign of just how much has changed in the utility industry, some power companies are now making the same kinds of arguments.

"Access to data and managing the data can be an opportunity for many of the utilities," said Lisa Frantzis, senior vice president at Advanced Energy Economy. "This has been a key topic that has come up throughout the United States when we've been having discussions about utility business model reform."

If it sounds like a brave new world for electric utilities, it is. The last decade has seen the growth of multiple technologies that are fundamentally disruptive to the traditional business model.

The National Academy of Engineering calls the electrification of the United States one of the greatest engineering achievements of the 20th Century. It can hardly be doubted — the intricate system of electric wires and power plants allowed for innovation and advancement. And it was the difficulty and expense of the task that led to utilities being regulated as a public service. Competition simply didn't work, when the costs to build a power plant or transmission line were so expensive as to preclude a second provider.

Jim Lazar, in the Regulatory Assistance Project's lengthy tome on electricity regulation, explained it like this: "The technological and economic features of the industry are such that a single provider is often able to serve the overall demand at a lower cost than any combination of smaller entities could."

Utilities are, as such, regulated as natural monopolies. They earn money through capital investments, a cost of service model that typically returns about 10%. It might not be perfect, but the model has stood for decades and electrified virtually the entire United States.

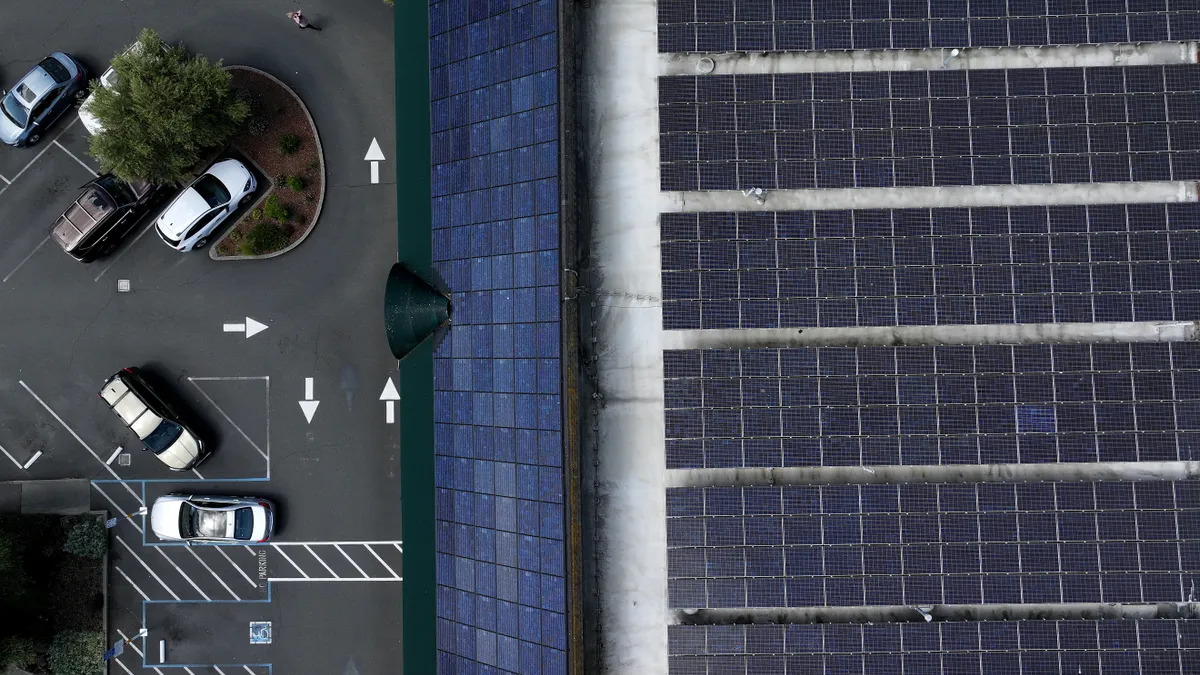

But the new disruption to utility business models has been fundamental. Distributed generation has changed planning, revenues and services, in some service areas. Energy efficiency has meant declining load for companies simultaneously tasked with selling energy and conservation. From rooftop solar to electric vehicles, and behavioral demand response to commercial energy storage projects, none of these new technologies resemble the old centralized power plant model.

Utilities "always had a real incentive to build a new power plant or invest heavily in capital assets," said Frantzis. But all that is changing, she said. Innovation is being driven by new types of technologies, and "they aren't huge capital investments."

In some states or cities, these changes are occurring more rapidly. Two years ago, Hawaiian Electric Co. temporarily halted connecting rooftop solar systems because the grid was becoming unstable. Other states remain, for now, far more reliant on traditional generation.

The relative constant in the mix is the delivery of the power. Distributed generation resources are driving changes in the grid, but the utility is still maintaining the poles and wires. And, increasingly, a complex communication network of devices, meters and resources that allow a wider range of resources to efficiently serve demand.

"The natural monopoly concept still applies to at least the network components of utility service," writes Lazar.

Collectively, it means utilities are beginning to operate as platform providers — akin, in ways, to the internet providers mentioned earlier. And while utilities still earn revenues from maintaining poles and wires, the key to their financial growth may be in finding other ways to make a buck.

New business models

Across the United States, regulators and utilities are taking a hard look at how the utility business model operates. While diverse resource mixes and market structures mean the change will not be uniform, there appears to be a widespread understanding that business as usual will not continue.

There are many states approaching the changes as grid modernization efforts. California, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Maryland, the District of Columbia, Ohio and other are all moving ahead with modernization plans that include updating the distribution system to accommodate resources like storage, microgrids, community solar and electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

But according to Frantzis, so far only New York has taken a front-to-back look at the industry. With its Reforming the Energy Vision proceeding, the state has gone beyond integrating new technologies and more towards creating new revenue streams.

"Utilities will continue to own and operate the distribution system," said Frantzis. "But now they're really going to be able to earn additional revenue above cost of service models, focused on the outputs and not just the inputs anymore."

Just last month, the New York Public Service Commission rolled out several orders that illustrate the state's direction. One included a new compensation structure for distributed energy resources, designed to help the state more accurately value solar power, energy storage and other local systems. Another focused on Distributed System Implementation Plans (DSIP) for utilities to help evolve their electric grids into platforms allowing third-party service providers access to power customers.

A key aspect in New York, and other states, is community renewable energy, particularly solar: bringing developers onto the grid to build solar projects for customers unable or unwilling to build their own. How those projects are selected, built and connected, how the shares are marketed, and how the utility profits alongside the developer, are all aspects of the new business models being considered.

Other specifics of the commission's orders included directing utilities to roll out an least two energy storage projects each by 2018, ordering a hosting capacity survey for distributed resources, and fully implementing an interconnection portal by October.

"New York has focused a lot of these early proceedings on business model reform, still allowing cost of service but now looking at performance incentives," said Frantzis. "REV has made some meaningful adjustments to how utilities operate and how they align incentives."

New revenue streams and investments

There are different kinds of changes in the works, as utilities make new types of investments.

New York and Illinois are both moving towards allowing utilities to ratebase software as a solution offerings. While that would allow utilities to include, for instance, cloud-based demand management platforms in their cost of service, it still maintains the old profit model.

On the other hand, last year Consolidated Edison petitioned the PSC for permission to develop an entirely new tariff — for data services requested by Community Choice Aggregation administrators, which would be considered a new Platform Service Revenues (PSR).

"Utilities have access to a lot of customer data and system-level data that could be very valuable third part entities," said Frantzis. A Nest thermostat offering or community solar projects will each require detailed information about the market.

"So the question becomes, should they be providing the data for free, or do they charge for it" said Frantzis. "The goal in New York in the long run, is where utilities would have PSR and maybe one of those is taking the data they have, aggregating it, and then selling it to earn additional revenues."

As ConEd pointed out in its application, the data service it is proposing can "only be provided by a utility, and stem from the Companies’ 'monopoly function.' ... only a utility has access to all customers’ retail choice status, block status, energy usage data, and customer information."

"There are a lot of opportunities for innovation in how utilities can make money," Frantzis said. But she stressed, this is not progress for the sake of progress.

New business models and revenue streams "have to be implemented because people are beginning to deploy some of these innovative technologies — like solar and efficiency — and utility revenues are going down," Franztis said.

"They have to do something—the old way of doing business is not going to work, going forward."