Shutoff moratoria across the country, allowing COVID-impacted residential and small business customers to defer utility payments without the threat of losing service, have been invaluable to millions, authorities on energy bill assistance say.

But when the vaccines are dispensed and the pandemic fades, any economic recovery will be impacted by potentially huge debts to utilities, debts that have yet to be addressed anywhere, experts said. State regulators will decide whether the indebted customers, all utility customers, investors, taxpayers — or some combination of those groups — should pay this bill.

Residential and small business customers could owe "$35 billion to $40 billion dollars to their utilities by March 2021," according to National Energy Assistance Directors' Association (NEADA) Executive Director Mark Wolfe. "Our new arrearage data shows that by then, individual unpaid bills may be as high as $1,500 to $2,000, which is as much as some customers pay for electricity in a year."

Utilities have done remarkable things to keep customers' lights on and "just get through the pandemic," spokespeople for San Diego Gas & Electric (SDG&E), Duke Energy and other utilities said. But policymakers and regulators must now plan to get working-class families the debt forgiveness that businesses and institutions got from the federal government's paycheck protection programs, Wolfe said.

"The reality is that someone is going to pay," said University of Florida Public Utility Research Center Director of Energy Studies Theodore J. Kury. Policymakers' and regulators' choices include requiring payment from indebted customers, shifting the debt to utilities and their ratepayers, imposing it on taxpayers, or some combination.

Although there may eventually be some good from the decision — like a better understanding of the effectiveness of moratoria or an improved relationship between utilities and their customers — they now must choose "how and when people pay," he added.

Moratoria on shutoffs and the utility experience

Starting in March, many states and utilities suspended power shut-offs for nonpayment. State-mandated or voluntary utility shut-off moratoria are now in place for 51% of the U.S. population (167 million people) across the country through Jan. 31, 2021, according to NEADA data from November.

As a result, utilities are seeing diminished revenues as they face unexpected expenses.

The pandemic "required us to dramatically adjust how we operate," Duke spokesperson Neil Nissan said. Like many utilities, Duke suspended disconnections for unpaid bills and waived late and other fees. The utility also helped customers enroll in local payment programs, the federal Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) or state and local assistance programs, including Duke Energy Foundation-funded local assistance agencies.

Duke expects COVID-reduced load, along with diminished revenues from waived payments and fees to lead to $0.25 to $0.35 in reduced earnings per share for 2020, which "equates" to estimated losses of $180 million to $260 million, Nissan said.

The utility has implemented work at home practices where possible and social distancing and other protective protocols, such as screening and testing. To restore power to 600,000 customers after an April 12 South Carolina storm, hundreds of line workers were brought in, but only after the utility ensured all appropriate COVID preventative protections were in place, Nissan said.

Comparable revenue issues, customer assistance programs, and employee protection measures were reported by Eversource Energy, Omaha Public Power District, Southern California Edison (SCE), SDG&E, and California community choice providers Silicon Valley Clean Energy and East Bay Clean Energy.

"Customers have called the utility in tears, concerned about not being able to pay their bills."

Jill Hanks

Spokesperson, Arizona Public Service

Other utilities offered more detail.

Arizona Public Service has suspended disconnections since March, utility spokesperson Jill Hanks said. They are expected to have "a negative impact" on 2020 operating revenue of "approximately $20 million to $30 million," according to the utility's Q3 earnings report. Regulators have approved $36 million in bill credits for customers to be paid for by all ratepayers and a shareholder-funded $8 million relief fund has also been implemented.

"Customers have called the utility in tears, concerned about not being able to pay their bills," Hanks said. Phone advisers have been given "special training" for such calls and "many have ended with expressions of relief and gratitude for $100 Covid-19 relief credits for residential customers, $1,000 credits for small business customers, or other crisis bill assistance."

SCE provided similar customer and employee protections and community support, and it has also been hit hard, including seeing 216 of its 13,000 employees test positive as of early November, the utility's temporary Director of Customer Operations and COVID-19 Customer Responses Katie Sloan said. September 2019 customer bills over 30 days in arrears totaled just over $97 million, but went up to $225 million in September 2020, according to SCE data filed Oct. 21.

SCE had over 1.38 million income-qualifying customers in its California Alternate Rates for Energy (CARE) program in September, up 200,000 from last year. In the same period, the number of customers with slightly higher incomes who are enrolled in the state's Family Electric Rate Assistance program (FERA) went up 8,000 from 20,109 to 28,561. This can be "largely attributed to the pandemic," Sloan said.

Utilities' response strategies have been similar across the country, the University of Florida's Kury said. The first concern was cash flow, but they resisted layoffs because of the need for personnel to keep the lights on. "The solution was to defer projects related to hardening of the grid or grid security, and any projects that could be put off, were put off."

Day-to-day system needs are being met, but longer-term "accessibility or reliability of service" could be impacted by investments deferred to meet "more pressing near-term cashflow issues," he added.

This potential threat to reliability reinforces the sense of a national emergency urgently needing attention that NEADA's Wolfe described.

Need for payment suspension continues

Every state in the U.S. had some version of a payment suspension, but many have ended, putting renewed pressure on customers.

The national and state assistance programs were not designed to address the COVID numbers, Wolfe said. "Applications rose slowly when expanded unemployment benefits were available, but they are beginning to overwhelm providers, and 74% of natural gas is used between November and March, which means heating bills are just starting to go up."

Another indication of the urgency are the recently imposed extensions of relief measures like bill moratoria and waived fees by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC), its Energy Division Director of Cost, Rates and Planning Simon Baker reported at a Nov. 12 workshop.

"A moratorium just kicks the can down the road. By the time the pandemic is over, these families may have a year's worth of utility bills."

Mark Wolfe

Executive Director, National Energy Assistance Directors' Association

Streamlined access to the CARE and FERA programs is necessary as arrearages grow "larger and older," CPUC Analyst Emma Johnston added. Medium and large commercial customers are "at imminent risk of disconnection."

IOU disconnections have been capped and the commission wants them ratcheted down, CPUC Regulatory Analyst Ben Menzies said. IOUs must also offer 12-month payment plans and attempt to enroll customers in assistance programs before disconnecting them.

But measures like these, likely to grow with the current spike in COVID cases and consequences, will only increase customers' eventual burdens, experts said.

"The paycheck protection program for businesses was to support the economy, and forgiving these working class families' utility bill debts to help them get back on their feet will do the same," Wolfe said. "A moratorium just kicks the can down the road. By the time the pandemic is over, these families may have a year's worth of utility bills."

Congress only provided $900 million for LIHEAP in the first stimulus bill and only proposed $4.5 billion in the recent stimulus talks, he added. "We think the need is $10 billion. It is a national problem and has to have a national solution."

Who pays?

Utilities' repayment plans may help people who still have jobs, but too many people don't, and they are sinking into debt they may never pay off, Wolfe said. Proposals to pass the burden to utility customers "adds to their debt, but forgiveness creates a taxpayer debt, and if we can do that for businesses, surely we can do it for working class people."

That must be done state by state because "it is well established by the law that electricity rates are state-level decisions and each state has its own priorities and policies for dealing with COVID," Kury said.

The "cost causality" principle of utility regulation assigns costs to those who cause them for the utility and "to the extent possible, the first choice for covering the debt is going to be direct assignment," he added. But customers are unlikely to be able to meet the growing debt, even with utility and federal payment assistance plans, and "it will probably be covered by someone else through a mix of other options."

One option is state-issued bonds. Secured by the state, their low risk profile typically attracts investors. The capital raised from their sale could pay off the debt. But, Kury said, because the cost of interest on government bonds would be paid by taxpayers, this option faces political opposition.

An alternative is imposing the burden on the utility. For an investor-owned utility, that transfers the debt to its investor-shareholders. But that would threaten the investor-appeal of a utility, which could lead to a compromise of its financial stability and ability to deliver services to its customers, Kury said.

"Utilities, regulators, and policymakers have learned more about customers and customers have learned more about utilities, and that greater understanding will have positive impact on the sector."

Theodore J. Kury

Director of Energy Studies, University of Florida Public Utility Research Center

Municipal utilities and cooperatives are essentially owned by their customers and have no shareholders, Kury said. There are no investors to shift the debt burden to, and shifting it to customers could create citizen and member opposition similar to the voter opposition created by the state-issued bond solution.

The utility's debt burden could also be spread among all ratepayers, he said. Most state regulators would be reluctant to approve this solution because of the upward pressure it would put on rates, especially because it would require a public proceeding in which ratepayer advocates and other stakeholders might block regulatory approval by making it politically controversial, he added.

Regulators have increasingly been interested in securitization of various ratepayer obligations, which limits the impact on rates and allows the debt to be "recovered over time," Kury said.

To do that, the utility creates and sells AAA-rated bonds, said Joseph Fichera, CEO at financial advisory firm Saber Partners. Secured by ratepayers, they would obtain favorable interest rates to limit rate impacts. With the capital from bondholders attracted by the low risk offering, the utility could pay off customers' COVID debt and spread it over time to limit rate impacts without involving shareholders or threatening utility balance sheets.

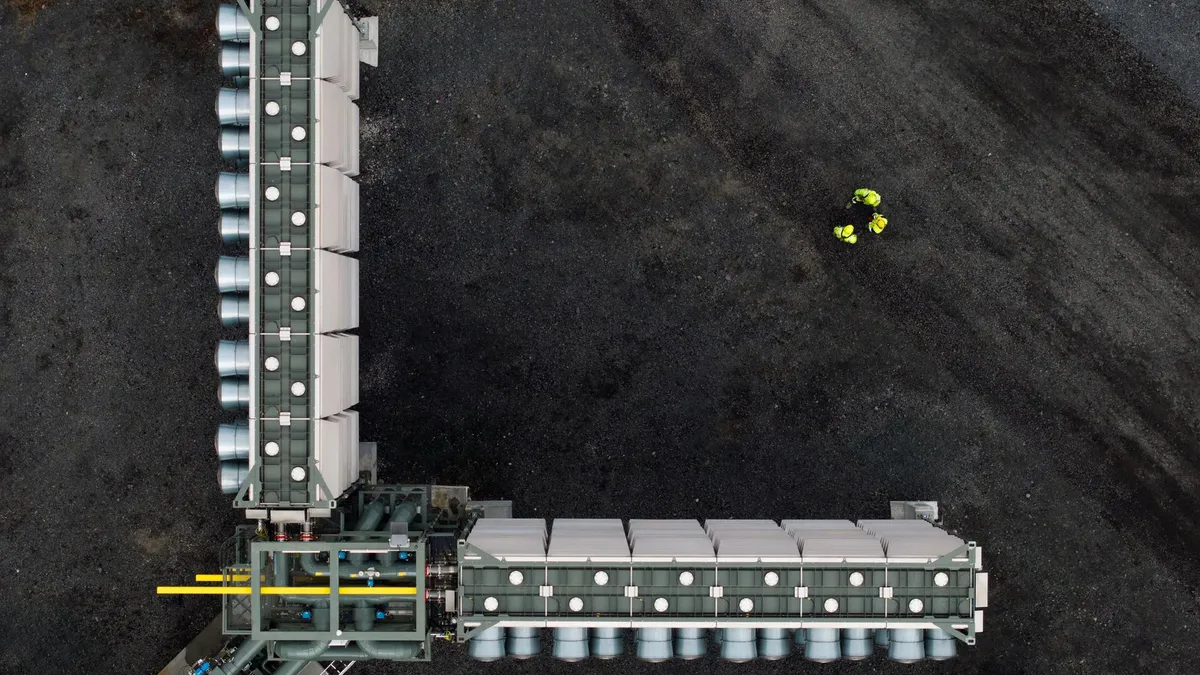

California provided the securitization option to resolve utility debt incurred during its 2000-2001 energy crisis, and its September 2020 Assembly Bill 913 approved its use to pay for wildfire losses, Kury said. It has also been used in Florida for hurricane recovery, in New Mexico to finance the San Juan coal plant closure, and Colorado policymakers are urging legislative approval to cover costs from new coal plant closures.

Financial strategies like securitization are "gaining traction" because they spread the cost across all ratepayers and over time, Fichera said. But regulators would have to decide how to implement those strategies because the law is not specific about how that is to be done, and regulators might be reluctant to take that on.

Eventually, all the stakeholders facing this burden could see two benefits from dealing with it, he added.

Two good things

The moratoria were imposed as an emergency response with little impact analysis, Kury said. This process will inform the use of moratoria and securitization in future emergencies because "we are going to learn if their costs outweigh their benefits."

A second good thing that will inform future emergencies is that utilities "have found new ways to interact with customers that have opened their eyes to new opportunities they may not have discovered without this emergency," he added.

"Utilities, regulators, and policymakers have learned more about customers and customers have learned more about utilities, and that greater understanding will have positive impact on the sector," Kury said.