Peter Kind’s 2013 "Disruptive Challenges" paper for the Edison Electric Institute put the utility sector on notice, encouraging it to proactively respond to the coming disruption of distributed energy resources with techniques to preserve their revenue streams, such as increased fixed charges for customers.

Now, Kind is back with a new paper — one with profoundly different conclusions than his 2013 project. In "Pathways to a 21st Century Utility," pubished by the clean energy nonprofit Ceres, he proposes a profound shift in how business should be done in the sector.

The ultimate aim, he told Utility Dive, is a more nimble and competitive sector, likely made up of smaller utilities, that would help resolve the regulatory bickering between utilities, policymakers, and third party energy providers that has characterized the period since the publication of his 2013 work. And that new sector wouldn't be one that pushes policy proposals like high fixed charges.

“We are not making progress at finding new pathways,” Kind said. “This paper talks about putting utilities in a much more proactive role in defining the future.”

There is urgency in the sector to find new pathways to help stave off the utility "death spiral" Kind wrote of in 2013, but it has been masked by low interest rates that support utility stock prices and high customer rates that still cover the cost of sector disruption.

But that fragile stability in the sector may not last, Kind believes, because customers and policymakers are demanding the deployment of more distributed energy resources (DERs) and the transformation of utilities' grid operations and business models.

When that disruption begins to impact investor returns, “the cost and availability of capital to fund the utility sector will suffer,” he warns.

“We must revisit the industry model to ensure alignment with customer and policy goals, while also ensuring that utilities and third-party providers are properly motivated to support their customer, societal and fiduciary obligations,” Kind writes. There must be benefits to “customers, policymakers, utility capital providers and competitive service providers.”

Kind's vision

The needed pathways must lead to utilities finding “new sources of revenues so they can fund their ability to be proactive and coordinate activities,” Kind said. That might be by owning DERs and other new technologies. Or it might be in “earning a fee by helping customers find the best way to do that.”

Four key changes are needed for a 21st Century electric utility, the paper reports:

- The utility must be engaged to be at the center of resource integration and stakholder collaboration, and achieve policy objectives through accountability and incentives.

- Regulators must shift focus to integrated distribution system planning and develop transparent accountability metrics.

- Utility revenues must reflect incentives earned for deployment of DERs, energy management services, and other new technologies, and must be penalized if this does not happen.

- Utility planning must identify the most cost-effective technologies and cap customer incentives based on the most economical options to achieve policy goals.

While Kind was thinking about these needed changes, the Obama administration finalized its Clean Power Plan (CPP), which aims to cut carbon emissions from the electricity sector 32% by 2030. That made Kind realize that “if there is a plan for emissions, there better be a plan for energy policy."

CPP implementation planning and a utility’s resource planning “dovetail,” he said.

“I’m not a scientist, but we have an environmental problem and we need to address our carbon footprint,” he added.

The CPP “may not be the best solution, but it is the solution on the table,” Kind said. “There may be lawsuits but it looks like this is the rule and as long as we are implementing it, it makes sense to develop a 21st century utility plan with it.”

Charting new revenue streams

Policymakers increasingly want customers to have the resources, technologies, and services that drive their policy goals, Kind said. “Utilities would be the logical distribution channel. They have the customer scale to drive change and they have the trust of those customers.”

Utilities need a level of cash flow to support their obligation to reliably serve all customers, but there is “a way to transition to the new model using current techniques,” Kind said. “Utilities can act as a distribution channel for competitive providers to offer the technologies and services and earn a market-determined commission.”

If utilities find and offer technologies and services that enhance customer value and meet policymakers’ efficiency and distributed generation goals, they would increase their revenue streams without investing as much ratepayre money.

“In the current paradigm, that reduces sales and revenues,” Kind said. “But in the new paradigm, the earnings for giving the customer access to that product is the utility’s incentive. To the extent it works, we can transition the business model over time because there will be those new revenue opportunities for utilities.”

A utility that spends $1 billion to build a power plant is likely to have a 15% cost of capital, Kind hypothesized. Covering that cost would require $150 million per year in ratepayer funds, which is the traditional rate of return for the utility.

But instead of that new power plant, a utility could meet the same power needs with a combination of distributed resources and demand side management techniques, he said. That might require $500 million, Kind said. At a 15% rate of return, that would cost $75 million per year. But those deployments themselves might earn $20 million.

“That is $95 million in revenue for the utility, which is $55 million less, but for half the capital investment,” Kind said. “Profitability goes from 10% to 11%."

He compared it to the banking sector: "If one bank offers 2% for a [certificate of deposit] and the other offers 2.5%, the choice will always be the 2.5% CD.”

At the same time, customers pay $75 million to cover the capital cost of deploying the new DERs and energy services, and $20 million to the utility for delivering them, so they get the same value for $55 million less.

That is a win-win-win-win, Kind said, because the investor prefers the utility to be more profitable instead of just bigger and third-party providers of the new services and technologies thrive.

There is the real possibility of smaller but more efficient utilities “as we move to a slower growth economy and there is pressure on costs,” Kind said. “We will need to figure out how customers can derive value for their services and that might mean thinking less about cost of service and more about value of service.”

Solar, rate design, and the failure of fixed charges

Solutions offered in 2013 have not led to the new pathways that are needed, Kind writes.

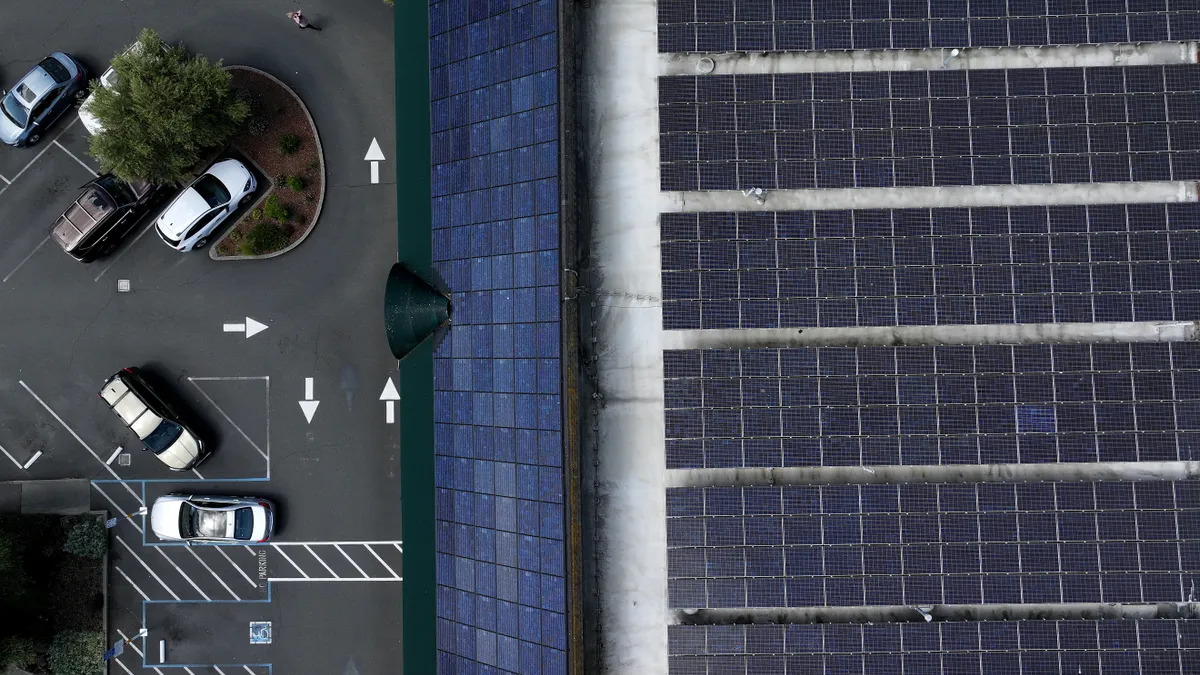

“It is clear from recent regulatory actions reconfirming support for DERs and net energy metering that policymakers are interested in DER development and customers want the option to choose their own energy supply.”

The utilities’ declining revenues problem described in 2013 remains, but the solutions offered then, particularly monthly fixed charges, have only led to bitter conflict between utilities and DER providers across the nation:

Instead of that, “we need to get everybody aligned and create the right kind of incentives so that everyone wins,” Kind said.

The problem with monthly charges is that they “remove the price signals needed to encourage energy efficiency and efficient resource deployment,” he wrote.

Better solutions to the utility revenue challenge than monthly charges would be “inclining block rates, reforming net energy metering, use of bidirectional meters, time-of-use rates, accountability incentives, and identifying new revenue opportunities for utilities.”

Demand charges might fit the equation only if they “meaningfully send usage price signals,” he added.

In states with net energy metering, rate increases continue to be necessary to offset the revenue lost from customers adopting DERs, he writes. “This scenario feeds a cycle of customer adoption of DERs and eventually results in increasing rates for non-DER customers.”

What is needed is “a value of solar approach,” Kind said. “Let’s figure out the cheapest way to provide renewables and use that as the basis for setting net energy metering rates.”

The retail rate credit now available for the net metered rooftop solar-generated electricity customers send to the grid is substantially higher than the wholesale price utilities pay for central station utility-scale solar, he said.

“That difference in price is more than the value rooftop solar could likely bring to the marketplace in terms of line loss savings, transmission cost savings, voltage support, whatever the factors are, you could drive a truck through that price differential,” he asserted.

As a result, the reimbursement credit for rooftop solar that comes from a value of solar study will almost certainly be substantially lower than the retail rate, he expects.

“I’m not picking on rooftop solar. Even rooftop advocates want a value of solar approach,” he said. “What is the best thing for society? What is the cheapest alternative, factoring in all cost components, using a value of solar approach?”

The section in his report on alternative tariff concepts is limited because the subject is “economically complicated,” Kind acknowledged.

It supports inclining block rates to drive efficient energy use. Decoupling of revenues from volumetric usage charges would protect utilities from revenue shortfalls during the transition to a new paradigm. Bidirectional meters would support whatever non-retail rate crediting of customer-sited DERs emerges from solar valuation. Optimized time-of-use rates would encourage customers’ adoption of new technologies and services.

A win for all

In most of the U.S., stakeholders are still not proactively working on comprehensive policies to meet utility business model challenges or working collaboratively “to find a solution that benefits all parties,” Kind writes.

“If we could start with a clean sheet of paper, how would electric utility services be structured? We would want to ensure that there was alignment of policy, customer, and investor goals in order to structure a product offering that satisfied the best interests of all major stakeholders, a win4.”

The objective is a business model “that enables customer value and service and achieves policy objectives to position us for the certainties of the future—particularly that the current concentration of fossil fuels in our energy mix poses significant risks to our economy and environment,” Kind writes.

To achieve this, he believes financially viable utilities are essential to finance and support a new grid, policymakers must define the goals and institute tariffs aimed at achieving them, and customers and third-party providers must be engaged, educated, and empowered.

“Whether these ideas will work for utilities is a function of how the tariffs are designed and what the incentives are and what the new revenue sources are,” Kind said. “We will see how much revenue they can capture in this new model. That will show how they will do and what customer rates will have to look like.”